I’ve been wanting to weigh-in with some of my own thoughts in the debate on historiography and historical method that Joe Cathay, Jim West, Ken Ristau, and Christopher Heard have been having of late, but haven’t had the time. Now it’s Friday night, my wife and kids are in bed, and while there are other things I should be doing, I thought that I would contribute to the discussion.

From reading the posts, I think that it would be good to back up the debate a bit and set some parameters and definitions. As I see it, there are some interrelated — yet significantly different — questions being bantered about:

- Is the Bible (better: some books of the Bible) historiographic, i.e., would some books of the Bible be classified as historiography in the ancient Near East?

- What does ancient historiography look like? How does it function?

- How would modern scholars employ ancient historiographic texts if writing a modern historiography of an ancient nation like Israel.

I will discuss all (or at least some!) of these questions in future posts. What I would like to do in this post is explore the simple question, “What is Histor(iograph)y?”

What is Histor(iograph)y?

In order to answer the first question, “what is history?” (or better framed as “what is historiography?”), we have to do a bit of history!

Generally speaking, contemporary thoughts on historiography are shaped by the change of views regarding the subject that occurred at the end of the Enlightenment. By the 19th century, the professionalization of historical studies led to a break with the rhetorical tradition, which saw the role of historical writing was to instruct the present by looking at the past. In contrast to this, a new view of historiography emerged which stressed the reliance upon — and “objective” investigation of — principle sources only. The goal of this new historical method was “merely to show how it actually happened” (G. Iggers, “The Professionalization of Historical Studies and the Guiding Assumptions of Modern Historical Thought,” A Companion to Western Historical Thought [Blackwell, 2002] 226).

This view, by definition, negated the validity of any theological, ideological or literary aspect in historical presentation. For example, Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886), the founder of “scientific” history, defined historiography as factual representation: a “strict presentation of facts, no matter how conditional and unattractive they might be, is undoubtedly the supreme law” of the “new” historiography. Under this definition, the goal of history writing is the “objective and scientific” presentation of what happened in the past and why it happened.

It was this definition of historiography (which I will call the factual representation model) that led other 19th century biblical scholars to question whether anything in the Bible could truly be considered “history.” For example, Wilhelm Vatke (1806-82) claimed:

The Hebrews did not at all raise themselves to the standpoint of proper historical contemplation, and there is no book of the Old Testament, however much it may contain material that is otherwise objectively historical, that deserves the name of true historiography.

Indeed, under the factual representation model of historiography, it would be hard to argue any different since the historical writings contained in the Bible are by no means “objective” or “scientific.”

Histor(iograph)y as Interpretation

I would contend that the definition of historiography as factual representation is inadequate not only for ancient history writings such as we find in the Bible, but also for modern history writings.

While all historiography is a recording of facts — factual representation — it is much more than that. A historian never just presents the facts; they always interpret the evidence according to their ideology, and then when they reproduce it they encode it according to the norms and customs of their times. Hayden White notes

Those historical propositions which are offered as mere descriptions of events, personalities, structures, and processes in the past are always interpretations of those events, personalities, and so forth? (“Rhetoric and History,” Theories of History [University of California, 1978] 7)

White argues that the 19th and 20th century historians who claimed objectivity and wrote “scientifically” were just as ideologically driven as any other historian. The difference is that under the history as factual representation model, historians employed a different rhetoric, a mode of discourse which was dispassionate and seemingly “scientific.” According to White, such historians exemplify “the mastery of the rhetoric of anti-rhetoric” (10).

White dismisses the presupposition that historical and artistic cannot coexist in literature. The presence of literary or ideological traits does not, in and of itself, preclude the identification of such a work as “historiography.” In fact, he would argue that all historiography must contain an “irreducible ideological component,” since by definition, the creation of a work of history — a coherent presentation of the past — must be culturally encoded. All historiography is culturally encoded, that is, it uses the cultural (religious or secular) images, symbols, and literary forms of the period or group. The fact that all historiography is culturally encoded does not disqualify it as historiography.

The perceived problem that many scholars from the 18th century to the present have with the historiography in the Bible is primarily with its ideology and cultural encoding. John Goldingay hits the nail on the head with this assessment:

I think part of the problem is that we are not really reconciled to the fact that the Israelite historians, like their ancient colleagues elsewhere, practice their art in a way so different from that of our post-enlightenment age; although of course the nature of the differences is well understood, at least at a scholarly level, we are so wedded to our modern way of writing history that the ancient way cannot appear to us as perhaps an alternative way and not just a primitive and inferior one (“That You May Know,” 81).

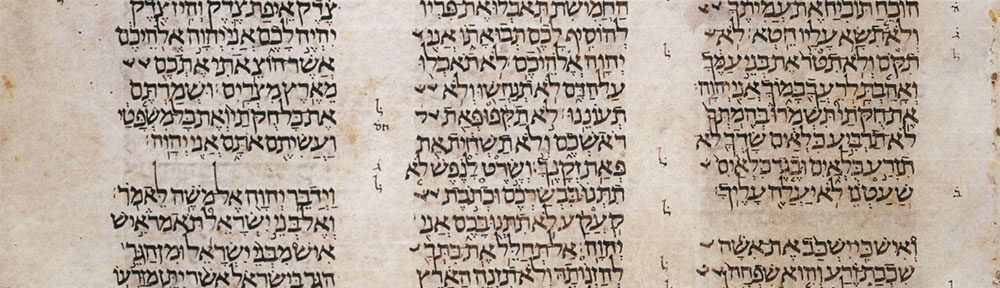

The Bible is a foreign and ancient book. When approaching the historiographic books in the Hebrew Bible we have to take into consideration how ancient historiography “works” as well as the different ancient literary conventions and codes it employs. It is to this task that I will return in my next post.

I have updated my database based on the Hebrew vocabulary of Bonnie Pedrotti Kittel, Victoria Hoffer, and Rebecca Abts Wright, Biblical Hebrew: Text and Workbook, Second Edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005;

I have updated my database based on the Hebrew vocabulary of Bonnie Pedrotti Kittel, Victoria Hoffer, and Rebecca Abts Wright, Biblical Hebrew: Text and Workbook, Second Edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005;