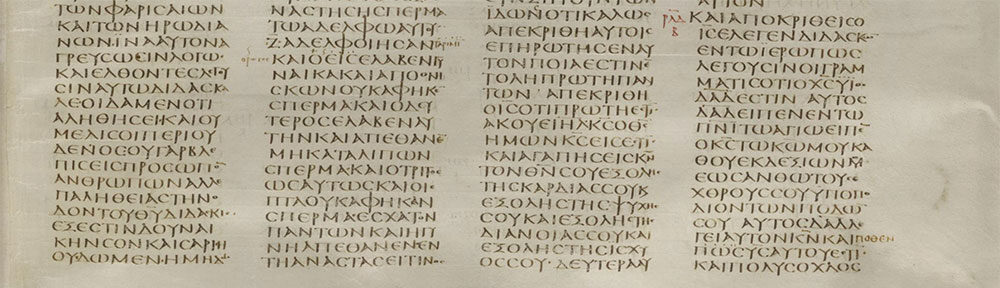

“The Sept-tu-a-what?” is what I hear from many of my students when I first mention the Septuagint in my introductory lecture on the text and transmission of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. By mid-term, however (or should I say by the midterm, i.e., the midterm exam), virtually all of my students are able to tell me that the Septuagint is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible begun around the third century BCE for the Pentateuch and completed sometime in the second or first century BCE for the rest of the books. Keen students should be able to further tell me that the title “Septuagint” comes from the Latin Septuaginta, which means “70” (thus the abbreviation LXX), and relates to the legendary origins of the translation by 70 Jewish elders from Israel (my “A” students may even relate how some versions of the legend report 72 elders were involved in the translation).

You may be wondering why I am bothering to relate something of my experience of teaching about the LXX. Just in case it didn’t come pre-marked in your calendar, February 8 is International Septuagint Day. This is a day established by the International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies (IOSCS) to promote Septuagint studies throughout the world.

In honour of International Septuagint Day, I thought I would provide some of the top reasons why we should study the Septuagint today:

- The Septuagint preserves a number of Jewish-Greek writings from the pre-Christian era not contained in the Hebrew Bible (known in Christian circles as the Apocrypha or the Deuterocanonical works)

- As such, study of the LXX can provide a glimpse into the thought and theology of diaspora Jews before the common era.

- For the majority of the books of the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible, the LXX provides us the earliest witness to the biblical text (earlier than most of Hebrew witnesses found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, for example) and is indispensable for textual criticism.

- The LXX provides a unique glimpse into the literary and textual development for some books of the Old Testament (e.g., Jeremiah, Esther, Daniel), as well as the sometimes fuzzy border between literary development and textual transmission.

- Insofar that all translations are interpretations, the LXX provides one of the earliest commentaries on the Hebrew Bible.

- The LXX gives us a glimpse of the shape of the OT canon before the common era (at least for Greek-speaking Judaism in the diaspora, perhaps not for Palestinian Jews).

- The LXX functioned as the Bible of most of the early Greek-speaking Christians (and continues to function as such for the Greek Orthodox Church).

- In connection with the previous point, the LXX often served as a theological lexicon for the writers of the NT, and as such it provides a fruitful avenue of research into the background of many of the theological terms and concepts in the NT.

- The LXX was the preferred Scriptures for many of the early church fathers and is essential for understanding early theological discussions.

- It’s a great conversation starter at parties (Attractive Woman/Man: “Read any good books lately?” Budding LXX student: “Why yes, I was just reading the Septuagint today!” Attractive Woman/Man: “The Sept-tu-a-what?” Budding LXX student: “Let me buy your a drink and tell you more…”)

I imagine more reasons could be thought of to read and study the Septuagint, but the above list is a good start. If you are interested to learn more about the Septuagint, I encourage you to work through my “Resources Relating to the LXX” pages, though I will mention three essential resources:

- A New English Translation of the Septuagint (Alberta Pietersma and Benjamin G. Wright, eds.; Oxford University Press, 2007). This is the best English translation available of the LXX and a great place to begin your study of the Septuagint. Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com

- Karen H. Jobes and Moisés Silva, Invitation to the Septuagint (Baker Academic, 2000). This is probably the best introduction for beginning students. It aims to familiarize readers with the history and current state of Septuagintal scholarship as well as the use of the LXX in textual criticism and biblical studies. For a more detailed description, see my review in the Catholic Biblical Quarterly 64 (2002) 138-140. Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com

- Septuaginta (Alfred Rahlfs, ed.; Editio altera/Revised and corrected edition by Robert Hanhart; German Bible Society, 2006). This is the popular edition of the Septuagint — and the only affordable version with the complete Greek text. Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com

I challenge you to think of some creative ways to celebrate International Septuagint Day today!