The Vatican made the news recently with the barring of the pronunciation of the name “Yahweh” — the proper name used for Israel’s God in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament — in Catholic worship. It appears that the use of the name Yahweh has been creeping into the Catholic churches liturgy of late, as it has been in the Protestant tradition as well. Here are some excerpts from the Catholic News Service report:

Bishop Arthur J. Serratelli of Paterson, N.J., chairman of the U.S. bishops’ Committee on Divine Worship, announced the new Vatican “directives on the use of ‘the name of God’ in the sacred liturgy” in an Aug. 8 letter to his fellow bishops.

….

His letter to bishops came with a two-page letter from the Vatican Congregation for Divine Worship and the Sacraments, dated June 29 and addressed to episcopal conferences around the world.“By directive of the Holy Father, in accord with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, this congregation … deems it convenient to communicate to the bishops’ conferences … as regards the translation and the pronunciation, in a liturgical setting, of the divine name signified in the sacred Tetragrammaton,” said the letter signed by Cardinal Francis Arinze and Archbishop Malcolm Ranjith, congregation prefect and secretary, respectively.

The Tetragrammaton is YHWH, the four consonants of the ancient Hebrew name for God.

“As an expression of the infinite greatness and majesty of God, it was held to be unpronounceable and hence was replaced during the reading of sacred Scripture by means of the use of an alternate name: ‘Adonai,’ which means ‘Lord,'” the Vatican letter said. Similarly, Greek translations of the Bible used the word “Kyrios” and Latin scholars translated it to “Dominus”; both also mean Lord.

“Avoiding pronouncing the Tetragrammaton of the name of God on the part of the church has therefore its own grounds,” the letter said. “Apart from a motive of a purely philological order, there is also that of remaining faithful to the church’s tradition, from the beginning, that the sacred Tetragrammaton was never pronounced in the Christian context nor translated into any of the languages into which the Bible was translated.”

This story was also picked up today by Christianity Today. The CT article surveyed a variety of opinions by evangelical leaders, some who agree with the Vatican ban and others who disagreed. Carol Bechtel, professor of Old Testament at Western Theological Seminary in Holland, Michigan is quoted as saying:

It’s always left me baffled and perplexed and embarrassed that we sprinkle our hymns with that name. Whether or not there are Jewish brothers and sisters in earshot, the most obvious reason to avoid using the proper and more personal name of God in the Old Testament is simply respect for God.

I’m not sure if I entirely agree. I do agree that we should not use the name if it is going to offend someone. When I teach Hebrew at the University of Alberta we discuss this issue in one of the first classes. I explain a bit about the name and how it has been preserved in the various textual traditions and versions, the early practice of avoiding the pronouncing the name, and current practices. Then we decide as a class what we want to do. Typically there are some Jews in the class who are uncomfortable pronouncing the name and we decide to read either “Adonai” or “haShem” (“the Name”) when we encounter the Tetragram (i.e., the four-letter name for God, YHWH or יהוה). At Taylor, however, where my students are all Christians, no one typically has any strong opinions either way.

Part of me wants to assert that if God didn’t want us to use the name, he wouldn’t have given it to the ancient Israelites. And I’m not sure if it is a matter of respecting God. I don’t like the practice of substituting a title (e.g., LORD) for a proper name, since it makes God rather impersonal.

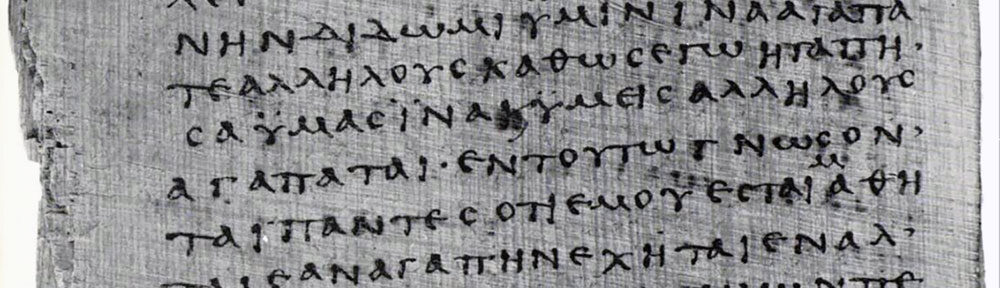

On the other hand, the tradition of avoiding the pronunciation of the name is ancient. The Greek translators of the Septuagint — with some exceptions such as P. Fouad 266 (Rahlfs 848) — used the Greek word for “Lord,” kyrios (κυριος) to represent the divine name. While there are some scholars who maintain the original Septuagint (LXX) wrote out the Tetragram in Aramaic or paleoHebrew letters akin to the the Minor Prophets scroll (8 HevXIIgr), these manuscripts represent more of an archaizing tendency than anything original (see Al Pietersma’s 1984 article “Kyrios or Tetragram: A Renewed Quest for the Original LXX”). Thus as early as the third century BCE, a surrogate was used for the Tetragram.

Setting the divine name apart was also reflected in the practice of some Dead Sea Scrolls writing the Tetragram with paleoHebrew letters. And the early Christians continued the tradition started in the LXX of substituting kyrios (κυριος) for Yahweh. Thus, this practice is found in early Christian tradition as well as most of the versions and translations throughout Christian history — which the exception of the KJV employing “Jehovah” in a handful of passages. Speaking of Jehovah… and yes, this is one of my pet peeves… I think it should be stricken from all hymn books and choruses! While we may not know exactly how the Tetragram was pronounced in antiquity (in this regard “Yahweh” is the best scholarly guess), we know for sure that it was NOT pronounced as “Jehovah”!

Jewish tradition is also pretty clear: pronouncing the divine name was avoided in order to ensure it is never misused (putting a hedge around the Torah) and also for respect. Manuscripts in the Masoretic tradition point the Tetragram with the vowels of title like Adonai as a perpetual ketiv-qere (interestingly, the Leningrad Codex is not consistent with what vowels are found with YHWH).

So when it comes right down to it, there is a long tradition of avoiding the pronunciation of the Tetragram, so perhaps we should follow suit.

What do you think? And what do you think is an appropriate surrogate?

Running through my mind is the Purcell setting of Jehova quam multi sunt hostes mei. You have to keep it here since this is what the composer set. Following John Hobbins, when I write a translation of a psalm, I use יהוה – The advantage in translation is that there is no need for certain words like O in ‘O LORD’. (The tetragrammaton never occurs in text with ‘my’). Having the Hebrew consonants in the English text reminds the reader that there is more to the text than words. It also makes clear when Adonai is used in contrast to יהוה.

When Moses asked god via the Burning Bush that, when asked by the Isrealites who gave Moses such authority, what name should he give, god did not say “Uh, well, it a tetragrammaton which shouldn’t be pronounced. Think of something to replace it. How about ‘LORD?'” (Exodus 3:13-14) I think the very reason god gave Moses the NAME to be pronounced among the Isrealites is the same reason god spoke in the creation story: that god, who is portrayed as almighty, transcendent, etc. in the Hebrew scriptures, is also personal. God’s name must be spoken among the faithful, so that they may proclaim they know this god. This idea that god’s name should not to be spoken was not the original intent of this Exodus account, which if one were to apply Midrashic hermeneutics, should set the tone for everything that follows. But instead some, like the pope, would insist more Pharisaical hermeneutics and build a “hedge around the law.”

Should the fact that the name Yahweh was purportedly used among the ancient Israelites themselves (i.e., within direct speech reported in the Hebrew Bible) be taken into account?

A different consistency about the pointing, however, is that it’s unpronounceable (or at the very least ungrammatical) within the Masoretic vocalization system, so that the odd pointing is another clue that something else is going on there. I’ve always found that interesting in and of itself.

Jehovah, Adonai, LORD, Yahweh: What’s In a Name?

Response:

1. In the 1960’s Christian churches across America began modifying the traditional Sunday morning service from a formal format to one more casual. This was a good idea. We should worship God “in Spirit and in truth,” not in the form of religion only.

Over the years, many adjustments have occurred in churches across the land:

Entered contemporary music and lyrics.

Entered modern musical instruments.

Entered various translations and versions of the Bible.

Entered casual clothing, replacing the traditional “Sunday best” garb.

Entered serving coffee and tea not only before and after the church service but even during the church service.

Entered (partially) replacing Bible reading during church services with poetry readings.

Entered sermons replacing the gospel message of repentance from sin and turning to God by faith in Jesus Christ to encouraging talks on how to be a successful Christian.

The above list includes features that have positive value and can contribute to the worship experience. But along with the quest for causal church services we lost the notion of respect and reverence during Christian worship and possibly for God Himself. It is often good to be causal but at the same time the sense of awe and reverence for God should not be lost. Using the Hebrew words for God and Lord by (or to) people who know nothing of the Hebrew language may tend to erode even more the few remaining fragments of respect and reverence. “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain” is a commandment that goes beyond crude curses and profanity. The commandment teaches that we should not use the name of God without its intended meaning and reverence.

2. People living in foreign countries and people knowledgeable about foreign languages are encouraged to not sprinkle foreign vocabulary when speaking and writing in their native tongue. Oriental people sometimes insert an English word or two into their conversations, newsprint and other publications. I must admit, it is often odd to listen to a conversation in Japanese and suddenly hear an English word. Did they know what they just said? Do they know the social, cultural context of the word? Often not.

The Hebrew words for God and Lord can be classified as “specialized vocabulary,” not intended for general conversation. For English speaking Christians, using the English words God and Lord is probably sufficient for most communication. The use of foreign words is usually a linguistically poor choice if the surrounding sentence is English. Dode-shou (I wonder).

Well, I don’t see anybody being struck dead, or cities being destroyed with fire and brimstone, so I guess God doesn’t care whether his name is used or what it is used for. Besides, how does anybody KNOW that’s his name? Maybe it’s Bob or Clyde or Edgar. If he didn’t want anybody using his real name, why would he tell it to anyone?

It seems possible that this sort of ecumenicism could be seen as condescending, or worse as co-opting. The rules about the Tetragrammaton do not exist in a vacuum, but in the context of a lived religion. Since obviously the church, certainly the Catholic Church, is not going to adopt Judaism as a way of life, it seems best to leave this kind of thing alone. But then, I could be wrong and perhaps it is a step in the right direction.

If Jewish scholars wanted to make the case that the prohibition is included in the Noahide Laws (particularly the one on blasphemy) them maybe it could be legitimate. But until then I don’t see even any ecumenical reason to do this (for a Christian).

Because it is ancient tradition, does that make it right? I guess I see YHWH giving his name to Moses as also a kind of progressive revelation. To the patriarchs he was Adoni, El Shaddai, El Roi, Elohim, Eloah, etc. working to where he finally let them in and gave the most personal of his names. But I could be off on this.