“Once upon a time there was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job” is the way I would translate the opening of the biblical book of Job. “There was a man…” (אישׁ היה) is a parabolic beginning to the story about someone called “Job” (iyyov; איוב). The name is of unclear etymology (although definitely not an Israelite name) and the place is similarly obscure (could be an area south of Israel around Edom [Jer 25:20; Lam 4:21] or perhaps associated with the Arameans [Gen 10:23; 22:21]).

The opening description serves to conjure up notions of antiquity and mystery about this ancient sage. Interestingly, Ezekiel 14:14, 20; 28:3 mention Job alongside two other ancient heroes: Danel (דנאל) and Noah. These references are to ancient non-Israelite heroes whose righteousness was legendary (note that the reference to “Daniel” is not to the biblical Daniel (דניאל); he would have been a child at the time of Ezekiel. Rather, the reference is to Danel, a legendary hero who we learn about from Ugaritic myths. E.g., the Aqhat Legend [CTA 17, COS 1.103] talks of a hero called Dani’ilu/Danel [dnil] who is childless, and because of his own righteousness is given a son, Aqhat, by the gods).

No matter how one takes the opening of the book, what is highlighted from the very beginning is Job’s integrity. He is described as “blameless and upright, one who feared God and turned away from evil” (1:1b). This hyperbolic fourfold description underscores Job’s superlative righteousness:

- “blameless” (תם). Used particularly in wisdom lit. as integrity or perfection

- “upright” (ישר). Lit. “straight”, often modifies “way”; used fig. for correct human conduct

- “fears Elohim” and

- “turns from evil” (see Prov 3:7, “Do not be wise in your own eyes; fear Yahweh, and turn away from evil”)

This fourfold description is suggestive as four is frequently used in the Bible to indicate completeness (cf. the fourfold destruction of all that Job has later in the chapter). Job’s superlative righteousness is also indicated by the fact that God has clearly blessed him:

There were born to him seven sons and three daughters. He had seven thousand sheep, three thousand camels, five hundred yoke of oxen, five hundred donkeys, and very many servants; so that this man was the greatest of all the people of the east (Job 1:2-3).

The numbers symbolic significance, suggesting completeness and perfection:

- Seven sons and three girls (= ten)

- Seven thousand sheep and three thousand camels (= ten thousand)

- Five hundred yoke of oxen and five hundred donkeys (= one thousand)

The opening ends with the note that Job is “the greatest of all the people of the east.” And in biblical parlance, the east was know for its sages — and he’s the best there was!

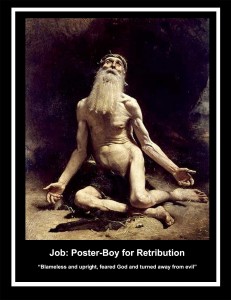

The point of this introduction is to present the biblical character of Job from the very beginning as the ancient Near Eastern sage par excellence. He is the best there was and perhaps best there ever will be. He is even better than Noah who is only provided a threefold description by the biblical narrator (Gen 6:9). if anyone should be blessed and allowed to prosper, it is Job. And as such, Job is the perfect set-up for the story of Job. He is the ideal test case. He is, as I like to call him, the “Poster boy for Retribution Theology” (see my poster image above). If God blesses (in this lifetime) those who are faithful to him (as many ancient Israelites believed — and way too many people still continue to believe today), and if suffering is the result of God’s judgment on sin, then Job should be blessed. And when evil comes upon Job, it must have been because he did something wrong (as Job’s friends suggest). It is this notion of retribution theology that the book of Job dismantles.

A most excellent observation, which is support by numerous examples in the New Covenant illustrations as well, such as John 9:1-3.

Oops – my comment should have read, “… supported by …” BTW, I like the poster as well.

Additional comment:

As pointed out in the original post, what we see as being popular within the Christian communities is simple ‘humanism’, i.e. God exists for the benefit of mankind, rather than the other way around.

If as you say the book of Job dismantles the “notion of retribution theology” why does Job end up getting back twice what he lost?

Fair question, Tim. The end of the book is unsatisfying for most modern readers. I would still contend that the book deconstructs typical views of retribution theology since Job’s suffering has nothing to do with anything he did wrong. It was not because of sin, contrary to what Job’s so-called friends argued. So while the book ultimately affirms that those who are righteous will eventually be blessed by God, it repudiates the notion of flipping the equation on its head and saying that those who suffer have sinned. Ultimately only God knows why suffering occurs (at least that is one interpretation of the theophanies at the end of the book). What do you think?

Oh, I agree with you 🙂 I just think it is an issue we too easily gloss over, which makes our claims about retribution sound hollow to many Bible readers. Your answer (and mine) however, makes me even more sorry for Job at the end of the book than the start! Since God never answers Job…

Tim, God does answer Job. “Where were you when I created the earth?” Quite a reprimand for questioning God’s motives, no? Hence, as Tyler notes, “Ultimately only God knows why suffering occurs …”

Job is not the only morality/wisdom fable in the MT. Jonah is, too. What I find very amusing about Jonah is just how old is the story of the “big fish that got away” … of, course, in this case, it’s the man who got away from the big fish. (And it is a “big fish,” [dag gadol], not a whale. Sigh, yet another relevant connotation lost in translation.)