Codex Sinaiticus (designated by the sigla א or S) was discovered in the nineteenth century by Constantine von Tischendorf at the Monastery of St. Catherine in the Sinai peninsula (hence its name). It is one of the oldest copies of the Christian Bible in Greek. In fact, it is the oldest complete uncial manuscript of the NT.

This is a special fifth post in a series on the textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. Other posts include:

- Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible – An Introduction (TCHB 1)

- Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible Resources (TCHB 2)

- Hebrew Witnesses to the Text of the Old Testament (TCHB 3)

- Early Versions of the Hebrew Bible (TCHB 4)

All posts in this series may be viewed here.

The story of the discovery of the codex is full of intrigue and scandal — OK, so it isn’t Indiana Jones, but for biblical studies it is pretty exciting! In search for ancient manuscripts of the Bible, Tischendorf first visited the monastery of St. Catherine in 1844. While visiting with one of the monks there he noticed a large basket of parchments being used to kindle the fire. Recognizing the parchments as parts of the OT in Greek, he persuaded the monks of their value and they stopped using them as a heat source. After some negotiations he was allowed to remove 43 leaves (which he figured was about one third of what was in the basket). Tischendorf eventually presented these manuscrpts to Frederick Augustus II, King of Saxony, who was his patron at that time. The 43 leaves were deposited in the university library at Leipzip and published under the name of Codex Friderico-Augustanus (MS gr. 1) in 1846.

The story of the discovery of the codex is full of intrigue and scandal — OK, so it isn’t Indiana Jones, but for biblical studies it is pretty exciting! In search for ancient manuscripts of the Bible, Tischendorf first visited the monastery of St. Catherine in 1844. While visiting with one of the monks there he noticed a large basket of parchments being used to kindle the fire. Recognizing the parchments as parts of the OT in Greek, he persuaded the monks of their value and they stopped using them as a heat source. After some negotiations he was allowed to remove 43 leaves (which he figured was about one third of what was in the basket). Tischendorf eventually presented these manuscrpts to Frederick Augustus II, King of Saxony, who was his patron at that time. The 43 leaves were deposited in the university library at Leipzip and published under the name of Codex Friderico-Augustanus (MS gr. 1) in 1846.

Tichendorf returned to Sinai in 1853 to secure the reast of the codex, but left empty handed — except for a scrap with a few verses from the book of Genesis. In 1859 he visited yet again and was successful (on his last scheduled day at the monastery) in viewing a large manuscript. After some more negotiations, he was allowed to take the manuscript to Cairo, where he copied it by hand in a period of two months. Then, taking advantage of some internal politics in the monastery and the Orthodox Church, in 1859 Tischendorf received permission to take the codex to St. Petersburg (presumably on loan) and presented it as a gift to the Czar Alexander II of Russia, the protecter and patron of the Greek Church, purportedly in return for influence in the election of a new Archbishop. Tischendorf published a facsimile edition in 1862; the original was deposited in the Imperial Library in St. Petersburg as Codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus in 1867. The codex was sold by a cash-strapped Russian government to the British Museum in 1933 for a sum of £100,000, half of which was raised by public support. The codex now resides in the British Museum as Additional MS 43725.

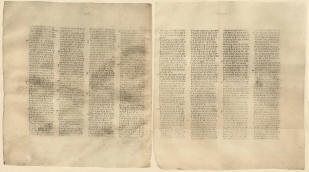

The codex is made of fine vellum (sheepskin and goatskin) with pages measuring ca. 15 by 13.5 inches (the original size is unknown due to binding). It has four columns per page (two columns in the OT poetic and wisdom books) with 48 lines per column. As with uncial manuscripts, there are no spaces between words, accents, or breathing marks.

The codex is made of fine vellum (sheepskin and goatskin) with pages measuring ca. 15 by 13.5 inches (the original size is unknown due to binding). It has four columns per page (two columns in the OT poetic and wisdom books) with 48 lines per column. As with uncial manuscripts, there are no spaces between words, accents, or breathing marks.

Based on scholarly reconstructions, the original manuscript is thought to have consisted of ca. 730 leaves and more than likely contained the entire Christian Bible (with Apocrypha), as well as The Epistle of Barnabus and the Shepherd of Hermas.

Today there are ca. 405 leaves extant in four locations:

- The British Museum has 347 leaves, 199 leaves containing 1 Chronicles 9:27-11:22, Tobit 2:2-14:15 (end), Judith 1:1-11:13, 13:9-16:25 (end), 1 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, Isaiah, Jeremiah 1:1-10:25, Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechiriah, Malachi, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Job; and 148 leaves with the complete NT as well as Barnabus and Hermas (to Mandates 4.2.3).

- The Universitats-Bibliothek at Leipzig has 43 leaves containing 1 Chronicles 11:22-19:17, 2 Esdras 9:9-23:31 [end], Esther, Tobit 1:1-2:2; Jeremiah 10:25-52:34 [end], and Lamentations 1:1-2:20. These leaves were published by Tischendorf with full-size litho-graphic facsimiles in 1844 as Codex Friderico-Augustanus (Leipzig, 1846).

- St. Catherine’s Monastery has 12 leaves and 14 fragments containing undisclosed portions of the Pentateuch. These were reportedly discovered in 1975 during renovations precipitated by a fire.

- Fragments of three leaves containing verses from Genesis 23-24 and Numbers 5-7 (MS. gr. 259 and MS. gr. 2), Judith 11:13-13:9 (Collection of the Society of Ancient Literature MS. O. 156), and Hermas Mandates 2.7-3.2 and 4.3.4-6 (MS. gr. 843) remain at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg.

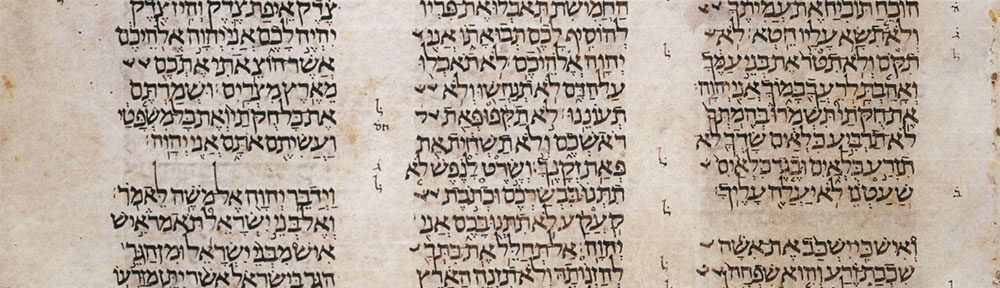

The script is written in a reddish-brown to black iron compound ink with an unornamented uncial hand. While originally thought to be the product of four scribes by Tischendorf and Lake (A, B, C, and D), recent scholarship has isolated only three hands, eliminating scribe C. Up to nine correctors have also been identified, two of whom were also original scribes.

Its date and provenance of the codex are uncertain. Based on the Eusebian apparatus, a clear terminus post quem can be set for around 300-340 CE. While a terminus ante quem is more difficult to ascertain, paleographically it has been set by a majority of scholars to the mid-fourth century CE based on a comparison with other uncial manuscripts, among other things (one scholar argues for a fifth century date, though with little support). The first two correctors are typically dated contemporaneous with the codex, while the other correctors are typically dated somewhere between the fifth and seventh centuries, and the last two to medieval times. While three different locations have been posited for its origin (Rome, Alexandria, and Caesarea); most scholars seem to prefer Alexandria or Caesarea.

Its date and provenance of the codex are uncertain. Based on the Eusebian apparatus, a clear terminus post quem can be set for around 300-340 CE. While a terminus ante quem is more difficult to ascertain, paleographically it has been set by a majority of scholars to the mid-fourth century CE based on a comparison with other uncial manuscripts, among other things (one scholar argues for a fifth century date, though with little support). The first two correctors are typically dated contemporaneous with the codex, while the other correctors are typically dated somewhere between the fifth and seventh centuries, and the last two to medieval times. While three different locations have been posited for its origin (Rome, Alexandria, and Caesarea); most scholars seem to prefer Alexandria or Caesarea.

The character of the text, with its many corrections, is uneven. The extant portions of the OT tend to agree with Codex Vaticanus, and are judged to contain superior readings in some books (e.g., 1 Chronicles, 2 Esdras, Isaiah). Similarly, the NT is of a high quality (with the exception of the book of Revelation) and tends to agree with Vaticanus (especially the Gospels and Acts). Canonically, some have considered the inclusion of Barnabus and the Shepherd of Hermas to be significant, though this is far from certain.

In 2006 the Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing at the University of Birmingham, in cooperation with the British Library and the three other holding libraries, began a digitization project to produce a new facsimile of the entire codex, as well as an online edition and other tools.

Internet Resources

- Description of the Codex with a few images from St. Catherine’s Monastery.

- A link to a full-quality image of a page of codex Sinaiticus with Jeremiah and Lamentations from ITSEE

- Tischendorf’s 1862 facimile edition of Sinaiticus is availble online from the Biblical Manuscripts Project

- Tischendorf’s personal account of the discovery of the manuscript is available here

Bibliography

- James Bentley. Secrets of Mount Sinai (Doubleday, 1986; Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com).

- Helen and Kirsop Lake. Codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus (Oxford University Press, 1911-1922).

- Bruce Metzger. Manuscripts of the Greek Bible (Oxford University Press, 1981; Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com).

- J. M. Milne and T.C. Skeat. The Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Alexandrinus (Oxford University Press, 1955; Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com).

- J. M. Milne and T.C. Skeat. Scribes and Correctors of the Codex Sinaiticus (Oxford University Press, 1938; ; Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com).

- T. C. Skeat. The Collected Biblical Writings of T.C. Skeat (NovTSup 113; Brill, 2004; Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com).

Pingback: Codex: Biblical Studies Blogspot » Blog Archive » Codex Sinaiticus Conference