The “Concept of Exile in Ancient Israel and its Contexts” workshop was held two weeks ago at the University of Alberta. Due to teaching and administrative responsibilities, I wasn’t able to attend much of the workshop, though I was able to catch the papers on one day and have lunch and dinner with the participants. It was great to meet everyone and talk some shop with them and get to know them a bit personally.

Exile and Ideology

One of the papers that piqued my interest was Martti Nissinen‘s “The Exiled Gods of Bablyon in Neo-Assyrian Prophecy.” In his paper, Martti examined an incident in Assyrian and Babylonian history when the Assyrian king Sennacherib razed the city of Babylon and deported its gods in 689 BCE. The deportation and/or destruction of a defeated nation’s gods (i.e., the statues) was a standard practice for the Assyrians (and other ancient peoples) and was considered an unambiguous sign of humiliation and demonstration of the power of the victorious monarch and his gods. What is particularly interesting is how the event was understood by each nation. Obviously the victorious nation interpreted the events as vindication of the superiority of their king and gods. More interesting is how the defeated nation understood the calamity ideologically. More often than not, the defeated nation would interpret the defeat and deportation of their gods as a sign that their gods were angry with them — not that the other nation’s gods were stronger.

There are many examples of this sort of ideological interpretation from the ANE as well as the Bible — here I am thinking of the capture of the ark of the covenant by the Philistines (1Sam 4-5) or, of course, Assyria’s destruction of the Northern Kingdom of Israel and Babylonia’s destruction and subsequent exile of Southern Judah. In both cases the biblical authors interpreted the defeat as Yahweh’s anger toward his unfaithful people, not the superiority of Assyria’s or Babylonia’s deities.

Divine Alienation — Divine Reconciliation

Nissinen continued his analysis of the deportation of Babylon’s gods to when the Assyrian king Esarhaddon, Sennacherib’s son, returned the gods to Babylon and rebuilt its temples in response to prophecy. In particular, Nissinen appealed to the prophecy of one La-dagil-ili which was spoken in Esarhaddon’s first regnal year:

Take to heart these words of mine from Arbela:

The gods of Esaggil are languishing in an evil, chaotic wilderness.

Let two burnt offerings be sent before them at once;

Let your greeting of peace be pronounced to them (SAA 9 2.3 ii 22-27).

Esarhaddon evidently took these words seriously and, based on the historical sources we have, concerned himself with the rebuilding of Babylon and restoring its gods. Esarhaddon’s move was not just political, it was theological. Restoring the gods to Babylon, according to Nissinen, not only quelled the anger of the Babylonian gods, but more importantly reestablished order in the cosmos. This divine alienation—divine reconciliation pattern is also found throughout the ANE and even in the Bible (e.g., Cyrus’s edict to allow the return and restoration of the Jerusalem temple).

Ideology, History, and Prophecy

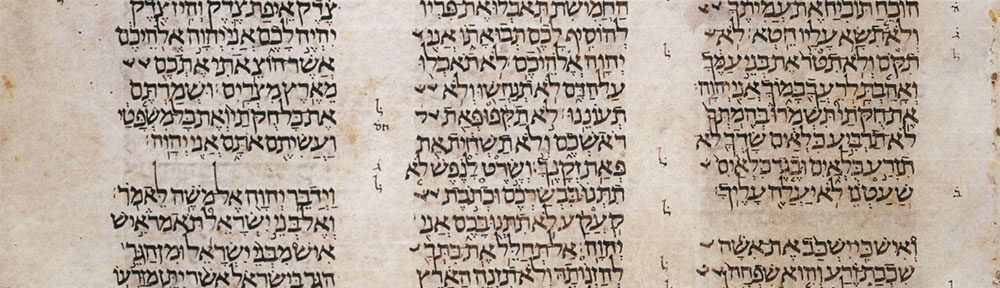

The ideas in Nissinen’s paper highlight an aspect of ANE historiography which we need to recognize in the Hebrew Bible. All ancient historiography (and perhaps all modern) is ideological. That is, it is written from the viewpoint of a faith in Yahweh who is active in the history of Israel. Yahweh’s supremacy is never doubted. If Israel is defeated, it is because of their unfaithfulness. If another nation defeats them, Yahweh is using that other nation to discipline his people. All of this is also true of Israelite prophecy.

This underscores the reality that all historiography (and prophecy) is interpretive. It highlights that the historical and prophetic writings of the Hebrew Bible are part and parcel of the ancient Near East and we shouldn’t be surprised that they reflect the literary practices and genres of the ancient world — perhaps much to the dismay of some evangelicals (this is one of the points Peter Enns makes in his Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament (Baker Academic, 2005; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com).

Resources

Martti Nissinen is Professor of Old Testament at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Many of the texts he referred to in his presentation are from his book, Prophets and Prophecy in the Ancient Near East (Writings from the Ancient World; Society of Biblical Literature, 2003; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com). He has also published Homoeroticism in the Biblical World: A Historical Perspective (Augsburg Fortress, 2004; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com).

I want to put a plug in for a book that I ordered for our library when I was doing my “

I want to put a plug in for a book that I ordered for our library when I was doing my “