Today is Remembrance Day (11 November) in Canada (as well as in the UK, Australia, and other Commonwealth nations), a day that we remember the sacrifices of members of the armed forces and civilians in times of war and peacekeeping.

All schools in Canada will have Remembrance Day assemblies and one of the traditions is to recite a famous Canadian poem about World War I, “In Flanders Fields.” Here is the poem:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

— John McCrae

One of my favourite Dire Straits songs is “Brothers in Arms,” a haunting ode to the foolishness of war.

These mist covered mountains

Are a home now for me

But my home is the lowlands

And always will be

Some day you’ll return to

Your valleys and your farms

And youll no longer burn

To be brothers in arms

Through these fields of destruction

Baptisms of fire

Ive watched all your suffering

As the battles raged higher

And though they did hurt me so bad

In the fear and alarm

You did not desert me

My brothers in arms

Theres so many different worlds

So many different suns

And we have just one world

But we live in different ones

Now the suns gone to hell

And the moons riding high

Let me bid you farewell

Every man has to die

But its written in the starlight

And every line on your palm

Were fools to make war

On our brothers in arms

May we never forget.

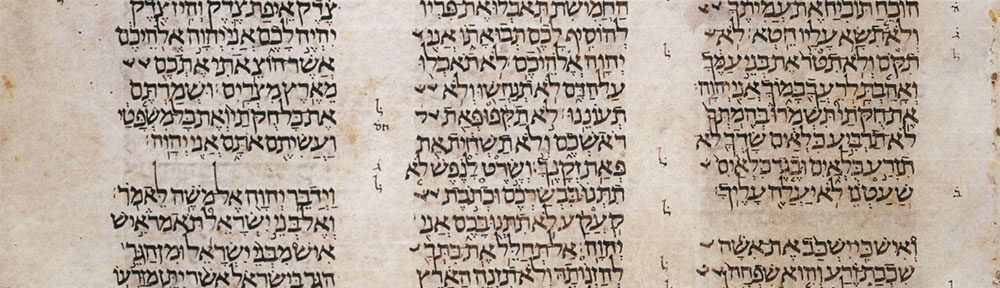

He shall judge between the nations,

and shall arbitrate for many peoples;

they shall beat their swords into plowshares,

and their spears into pruning hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more (Isa 2:4)

If you think I meant black cats in the title, you’re wrong.

If you think I meant black cats in the title, you’re wrong.