Labels don’t really matter that much, do they? A rose by any other name would still smell as sweet — or so they say. A little while ago there was a discussion on the biblical studies email list about different names for the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible/Tanak. This discussion highlighted the significance that each of the different monikers has as well as potential problems with pretty much all of the terms. When it comes right down to it, it does make a difference what label you do use since each of the names relate to a particular community of faith and audience. That being said, I don’t think there is anything wrong with employing the various labels at different times depending on your intended audience.

From the get go, it should be noted that all of the different terms are, in fact, external labels. The collection of books that make up the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible/Tanak do not have any self-referential label. The closest you get to a self-referential title are the references to parts of the canon by the terms such as “Torah,” the “Torah of Moses” (Ezra 3:2; 7:6; Neh 8:1), the “Torah of the LORD” (Ezra 7:10), or the “book/scroll of Moses” (2Chron 25:4; 35:12; Neh 13:1).

Once you get outside the books of the Hebrew Bible you find references to “the law of the Most High,” “the wisdom of all of the ancients,” and “prophecies” in Sirach 38:34-39:1. Similarly, in the Greek translation of Sirach (completed around 132 BCE), you find reference to the Law, Prophets, and the “other books” — the last phrase being a disputed reference to the third division of the Hebrew Bible. A similar (disputed) reference to the tripartite Hebrew canon are found in 4QMMT, while there are a few reference to a bipartite canon in other DSS such as the Community Rule (1QS) and the Damascus Document (CD).

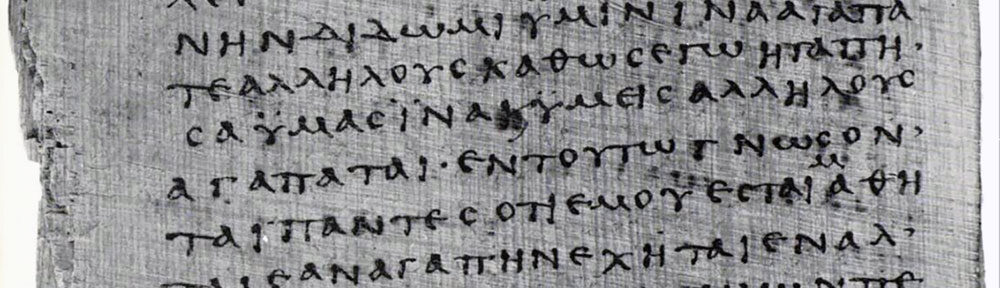

Within the Christian New Testament the books of the OT are referred to variously as “the Law and the Prophets” (Matt 7:12; 22:40; Luke 16:16; Acts 13:15; Rom 3:21) or “Moses and the Prophets” (Luke 16:29, 31; 24:44) or the like. One of the most common ways the NT refers to the books of the OT is by the generic term “scripture” (Gk. γÏ?αφὴ; usually in the plural, “scriptures”). So for instance, in 2 Timothy 3:16 the books of the OT are referred to as “Scripture” that is “God breathed” (Gk. θεόπνευστος).

The point of this survey is to illustrate that there was no uniform way that Jewish or later Christian communities referred to the collection of books that make up the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible prior to the second century CE.

The traditional Christian label is the Old Testament. This label for the books otherwise known as the Hebrew Bible or Tanak (note that in some traditions it also includes additional apocryphal/deuterocaonical books) is probably the most common label used overall. Its first known usage appears near the end of the second century CE. Melito of Sardis reportedly went to Palestine and “learned accurately the books of the Old Testament/Covenant” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 4.26.14). Irenaeus also employed the term, though it is only after him that you find undisputed uses the labels “Old Testament” and “New Testament” for the two collections of books in early Christian writings (e.g., Clement, Tertullian, Hippolytus, etc.).

Since this term arose within a Christian context, it isn’t surprising that it is tied to a Christian understanding of these books being only one part of the two part Christian Bible: The Old and New Testaments. Historically, however, there is some difference of opinion within Christian circles what books actually make up the “Old Testament.” The early history of the debate over certain books is quite complex. It ended up that the Protestant tradition limited the term to refer to the books of the Hebrew Bible, while other Christian traditions, e.g., Catholic and Orthodox, include the books commonly referred to as apocryphal or deuterocanonical.

One of the main objections for using this term in biblical scholarship is that it clearly presupposes a Christian understanding of the Bible, which not everyone in biblical studies (obviously) shares. But even within Christian circles, this label is considered misleading by some since it may be interpreted as unnecessarily devaluing one section of the Christian Bible by calling it “old” or by implying that the “new” testament supersedes the “old” testament (the different understandings of the relationships between the testaments is beyond the scope of this post). This dissatisfaction spawned the use of the terms First and Second Testament. These terms are an attempt to recognize the two parts of the Christian Bible without some of the negative baggage associated with “Old” and “New Testament.” I believe this term was coined by James Sanders and has been adopted by the Biblical Theology Bulliten and a growing number of Christian scholars. Even John Goldingay employs it throughout his recent book Old Testament Theology: Israel’s Gospel (IVP, 2003; he only uses the term after the first chapter).

The label Hebrew Bible originates within the Jewish community and is gaining ground in academic biblical studies. It is considered less ideologically loaded than OT, though it has its share of problems. Perhaps the most obvious problem is that it is imprecise, since some of the books are actually written in or contain Aramaic portions. It still conveys religious overtones by including the term “Bible,” while Christians may object because it obscures the connection between the Hebrew Bible and the Christian New Testament. It also doesn’t take into consideration traditions that hold to the expanded Christian canon including the apocryphal books.

Another popular Jewish term for the Old Testament is the Tanak. This term is an acronym for the three major divisions of the Hebrew Bible: Torah, Nebe’im, and Ketubim — TaNaK (תורה × ×‘×™×?×™×? וכתובי×? in Hebrew). This is perhaps one of the most common terms used within the Jewish community. Since the label is tied to the contents and order of the Jewish Hebrew Bible, it has the same, if not more, limitations as the term Hebrew Bible. Of course, this traditional Jewish division and ordering of the books appears to be quite old and even reflected in some of the NT passages noted above (also see Matt 23:35).

Other terms have been suggested, but none have really gained widespread usage. Perhaps the traditional labels, albeit problematic, are the best we have. As long as they are used with charity and understanding, I don’t see much of a problem. I have never been offended by any of my Jewish friends referring to the Old Testament as the Hebrew Bible or the Tanak, nor do I think they have been offended when I or other Christians refer to the Old Testament. I probably use the awkward “Old Testament/Hebrew Bible” the most, and reserve “Old Testament” when engaging specifically Christian theological topics and concerns. And I’m still not sure what I think of “First and Second Testament.”

What label(s) do you use and why?