I just got home today (early in the morning due to flight delays) from the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies annual meeting at York University, Toronto. I was hoping to post some reports from the meetings, but my dorm room at York didn’t have internet access (and no shower curtain — I felt like Jesus walking on water). In the next few days I will post some of my reflections from the meeting.

I just got home today (early in the morning due to flight delays) from the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies annual meeting at York University, Toronto. I was hoping to post some reports from the meetings, but my dorm room at York didn’t have internet access (and no shower curtain — I felt like Jesus walking on water). In the next few days I will post some of my reflections from the meeting.

Sunday morning (Sunday 28 May) the session of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament / Bible Hébraïque/Ancien Testament met. There were a number of interesting papers as well as some good discussion. Here are some highlights.

In the Beginning… of CSBS

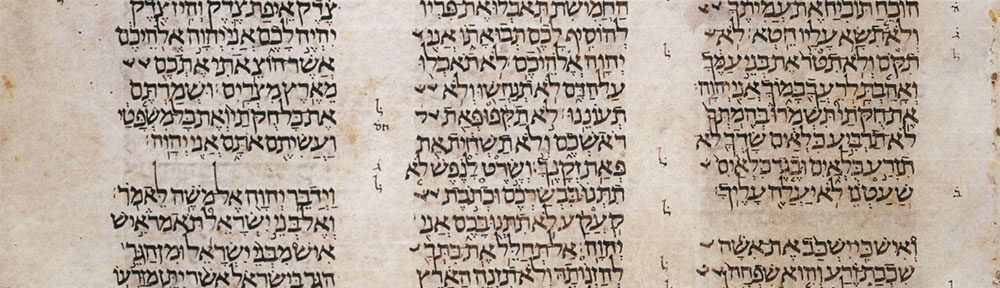

The very first paper of the conference was by Robert D. Holmstedt, the recently appointed Assistant Professor of Ancient Hebrew and Northwest Semitic Languages, Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations at the University of Toronto. He presented an interesting paper on “The Restrictive Syntax of Genesis 1:1.″ Beginning with the observation that while many (most?) scholars have departed from the traditional understanding of בר×?שית as an independent phrase with grammatical reference to “THE beginning,â€? it continues to thrive as reflected by the majority of modern translations. He also noted how advocates of the dependent phrase position (e.g., “when God beganâ€?) struggle with a precise and compelling linguistic analysis (how can a verb function as the absolute of the construct phrase?). In his paper, Holmstedt offered a linguistic argument that both provided a simpler analysis of the grammar of Gen 1:1 and clarified that the traditional understanding of a reference an “absolute beginning” cannot be derived from the Hebrew grammar of the verse. Based on his doctoral research into the relative clause in Biblical Hebrew, Holmstedt argued that the phrase is best understood as an unmarked, restrictive relative clause (a “restrictive” or “limiting” relative clause is one that providesmore information about the head word), and he translated the phrase as, “In the initial period that God created the heavens and the earth.” Thus, the phrase is not referring to an absolute temporal designation (“In THE beginning”), but is referring to the the particular begining from which the rest of the story in Genesis proceeds. Rather, there were potentially multiple בר×?שית periods or stages to God’s creative work. While I have always leaned towards taking the construction as an indefinate adverbial nominal suggesting a relative temporal designation (i.e., “when God began to create…”), I have never been satisfied with the syntax of such a construction. Holmstedt’s analysis provides a way of understanding the phrase that is both syntactically plausible and meshes with other ANE creation stories.

Burning (Ring Of) Fire

Next, Christian A. Eberhart from Lutheran Theological Seminary, Saskatoon, read his paper “The Cult Term ×?ִש×?ֶּה (isheh): Remarks on its Meaning, Importance, and Disappearance.â€? Contrary to the views of such heavyweight biblical scholars such as Jacob Milgrom and Rolf Rendtorff, Eberhart argued persuasively (IMHO) that the Hebrew term ×?ִש×?ֶּה is best understood to include connotations of burning. He suggests that the best translation is, in fact, “fire offering.â€? Building on this broader understanding, he also showed that the term was a key notion of the sacrificial cult in which it can also be used as a comprehensive term for all sacrifices — especially in priestly texts.

The Matrix Revisited

Derek Suderman, a doctoral student at Emmanuel College, Toronto, focused on critical method and the book of Psalms in his paper “The ‘Complementary Hypothesis’ Reconsidered: Exploring Methodological Matrices in Psalms Scholarship.” Suderman wanted to debunk the notion that different critical approaches to the biblical text are complementary stages in the process of exegesis. The three pillars of the “complementary method” that Suderman questions are: (1) different approaches illuminate different aspects of the biblical text; (2) the different methods represent distinct steps in exegesis; and (3) the goal of biblical exegesis is to achieve a synthesis of the different methods. On the whole, I think Suderman was sucessful in showing how the different critcial approaches conceive (indeed, generate) the relationship between the author, editor, original text and setting of individual lament Psalms in such different ways so as to be incompatible. These elements are so inter-connected that changing the meaning or function of one element in the system affects all of the others. And since different biblical criticisms reflect divergent matrices, the “complementary hypothesis” of biblical criticisms is highly questionable. While I agree with Suderman’s main argument, I think that some methods are more complementary than others — especially those which developed in relationship with each other (e.g., form and rhetorical criticism). I tend to be very ecclectic with my method, and while all of the different methods may have some incompatibilities, they all can highlight certain things about the text.

Hosea’s “Flagrant Hussy”

The third paper of the morning was “Fresh Light on Hosea from History, Archaeology and Philologyâ€? by J. Glen Taylor, from Wycliffe College, University of Toronto. Taylor shared a number of insights on Hosea from his work for the Illustrated Bible Background Commentary series (Zondervan, forthcoming 2007). For example, contrary to Freedman and Andersen, he argued that Hosea’s wife was likely a “flagrant hussy” at the time God told him to marry her. Moreover, if one compares 1:2 both to 2:3 [ET 2:1] and to Ancient Near Eastern adoption formulae, it seems likely that God told Hosea also to adopt children previously borne by his new bride (i.e. children other than the three she bears in 1:3–9). One of the neatest points was his understanding of Hosea 14:9 [ET 14:8] as containing a subtle wordplay that mock the goddesses Anat and Asherah. While I think there is something to Taylor’s reading, in the discussion after the paper Holmstedt raised a good point that recent research suggests native Hebrew speakers do not tend to isolate roots and perhaps these sublte wordplays would be lost on them. While that may certainly be the case, the history of interpretation does show that native Hebrew speakers did put significant stock in word plays (And they are just so much fun to point out!).

Samson: From Zero to Hero

Next up was Joyce Rilett Wood, a PhD graduate from the University of Toronto. Her paper, “The Birth of Samson” explored the parallels between the story of Samson (Judges 13-16) and the legends of Heracles. She highlighted a number of well-recognized parallels, such as the role of lions and women in the respective stories. Beyond the these well-recognized parallels, she also argued that the story of Samson’s conception and birth (Judges 13) is parallel to the miraculour conception and birth of Hercules. While I think that Rilett Wood pointed out some significant parallels, she didn’t spend any time explaining the significance of the parallels (or perhaps more importantly, the differences). I was not convinced by her reading suggesting Samson’s mother conceived him through the direct agency of God. If anything, I think that there are far more compelling links between the other births in the Bible and the birth of Samson than the birth of Hercules.

Speech, Prayer, and Rhetoric

Finally, Mark Boda from McMaster Divinity College presented a paper entitled, “Prayer as Rhetoric in the Book of Nehemiah.” Taking the lead from recent literary models for the interpretation of prayer, Boda looked at the role of prayer within the rhetoric of the book of Nehemiah. Based on his rhetorial analysis, Boda argued that the initial prayer in Neh 1:5-11 draws the reader’s attention not only to the piety of the main autobiographical character, a piety that will be showcased throughout the book, but more importantly to the role this character will play in creating conditions which will facilitate similar piety in the community as a whole. While the first six chapters of the book of Nehemiah focus on the main character as an agent of renewal of the city’s infrastructure, the second half shifts this focus onto the main character as an agent of spiritual renewal. The placement of the two longest prayers in the book at Nehemiah 1 and Nehemiah 9 accentuate this rhetorical shift in the book as a whole. I especially liked Boda’s summary of the purpose of speech in ancient narratives (e.g., to advance plot, express author’s ideology, provide an alternative viewpoint, etc.).

All in all, it was a good morning. One thing that sets CSBS meetings apart from a large meeting like the SBL is the intimacy.

The Ancient Historiography Seminar / Groupe de Travail sur l’Historiographie Ancienne of the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies invites papers on self-identification, community identity, and ethnicity in Judahite/Yehudite historiography for the 2007 Annual Meeting at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon (May 27-29).

The Ancient Historiography Seminar / Groupe de Travail sur l’Historiographie Ancienne of the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies invites papers on self-identification, community identity, and ethnicity in Judahite/Yehudite historiography for the 2007 Annual Meeting at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon (May 27-29).

Ehrman’s lecture focused on uncovering the significance of the “Gospel of Judas,” the recently uncovered second-century gnostic gospel that has been all the rage in recent months. In a nutshell, the significance of this gospel text, according to Ehrman, is not because it is somehow more authentic than the canonical gospels or because it somehow undermines the very foundations of Christianity. Rather, its real significance is because it is a serious document of real historical significance which gives us a glimpse into gnostic thinking in antiquity. According to Ehrman, the text’s closest ties are with various Sethian forms of Gnosticism, although it has clear alliances with other forms of early Christian thought (Valentinian, Thomasine, Marcionite). He even argued that there appears to be remnants of Jewish apocalyptic theology in the surviving text. He also noted how it has some unique characteristics compared to other gnostic texts, such as the sympathetic portrayal of Judas as the only disciple who really understood Jesus’ work and message (sounds like The Last Temptation of Christ). The lecture was well done, although considering his audience was mainly academics, he could have raised the level of the lecture a bit.

Ehrman’s lecture focused on uncovering the significance of the “Gospel of Judas,” the recently uncovered second-century gnostic gospel that has been all the rage in recent months. In a nutshell, the significance of this gospel text, according to Ehrman, is not because it is somehow more authentic than the canonical gospels or because it somehow undermines the very foundations of Christianity. Rather, its real significance is because it is a serious document of real historical significance which gives us a glimpse into gnostic thinking in antiquity. According to Ehrman, the text’s closest ties are with various Sethian forms of Gnosticism, although it has clear alliances with other forms of early Christian thought (Valentinian, Thomasine, Marcionite). He even argued that there appears to be remnants of Jewish apocalyptic theology in the surviving text. He also noted how it has some unique characteristics compared to other gnostic texts, such as the sympathetic portrayal of Judas as the only disciple who really understood Jesus’ work and message (sounds like The Last Temptation of Christ). The lecture was well done, although considering his audience was mainly academics, he could have raised the level of the lecture a bit.

Morrow’s address was entitled, “Violence and Transcendence in the Development of Biblical Religion.” He began by noting the disappearance of individual lament/complaint prayer in the Second Temple period. The laments you do find in the Second Temple period differ from the earlier individual complaint psalms in that they tend to be in a narrative context, they neglect individual suffering, combine individual and communal elements, and have a unique status. According to Morrow, instead of individual lament psalms where the psalmist complains to God (and sees God as the problem in many cases), in the Second Temple period you see the development of prayers against demonic attack. The therapeutic impulse expressed in the earlier laments now shifts to incantations and psalm-like texts that have as their goal to expel demonic attack.

Morrow’s address was entitled, “Violence and Transcendence in the Development of Biblical Religion.” He began by noting the disappearance of individual lament/complaint prayer in the Second Temple period. The laments you do find in the Second Temple period differ from the earlier individual complaint psalms in that they tend to be in a narrative context, they neglect individual suffering, combine individual and communal elements, and have a unique status. According to Morrow, instead of individual lament psalms where the psalmist complains to God (and sees God as the problem in many cases), in the Second Temple period you see the development of prayers against demonic attack. The therapeutic impulse expressed in the earlier laments now shifts to incantations and psalm-like texts that have as their goal to expel demonic attack.