I fancy myself a wee bit of a textual critic, though through my studies with the likes of Bruce Waltke, E.J. Revel, Stan Walters, Al Pietersma, among others, I perhaps more than anything else recognize the hard work and commitment necessary to do textual criticism properly. Knowing something about how to do textual criticism is one thing, having the mastery in the requisite languages as well as a thorough understanding of the textual witnesses, including their predilections and tendencies, is a daunting task. That being said, I figured I would do a few posts on the textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible, including some discussion of method and manuscripts, some examples, and available resources to aid the student in doing some text criticism. These posts will be based on my research, some of my class lectures as well as an article I wrote with Bruce Waltke a number of years back.

Defining Textual Criticism

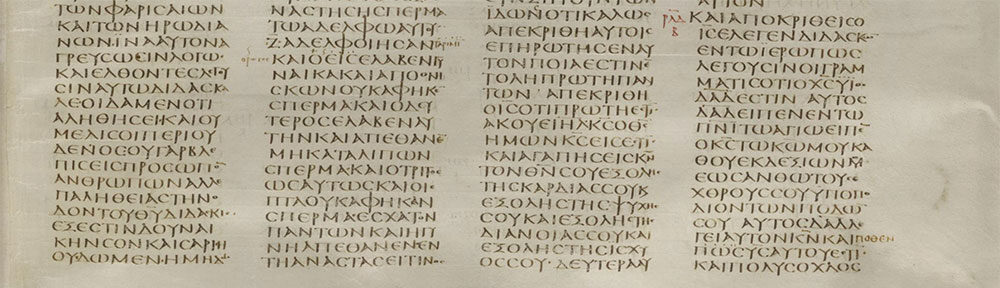

This first post will highlight the need for textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible. But before I get to that, I should perhaps define “textual criticism.” Textual criticism is the name given to the critical study of ancient manuscripts and versions of texts, usually for the purpose of restoring the original text (or the best/most reliable reading of a text), or as we will discuss later on, restoring the original edition of the ancient text. (I should note that some critics are not very optimistic about being able to restore the “original” texts or editions and are happy to just study the different manuscripts to see how texts changed over time and reflect their socio-linguistic contexts). Its technique involves an investigation of the textual witnesses to the Hebrew Bible, their histories, and evaluating variants in light of known scribal practices.

The Need for Textual Criticism

First and foremost, textual criticism is necessary because there are no error-free manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible. All the textual witnesses to the Hebrew Bible are the results of a long process of transmission. The text has been copied and re-copied by scribes of varying capabilities and ideologies through many centuries. No matter how good a scribe may have been, errors inevitably crept into his or her work. Even critical editions of the Hebrew Bible such as Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), contain printing errors. While some of these errors reflect errors in the medieval manuscripts on which they are based, others were introduced with printing.

A second reason why textual criticism is necessary is the realization that the further back we go the greater the textual differences we will find between manuscripts. Variants in the medieval Hebrew manuscripts (dated ca. 1000 to 1500 CE) as collated by the likes of Kennicott and de Rossi are small in comparison to those found in the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), which are more than a millennium older. In fact, the further back we go in the textual lineage the greater the textual differences we find between manuscripts.

Finally, in addition to these inevitable accidental errors there are intentional “errors” found in the texts. Scribes occasionally changed the text for linguistic and exegetical reasons, and, rarely, for theological reasons. I will talk about these sorts of “errors” or intentional changes in a future post.

All this means that if we are at all concerned about establishing an “original text” or an “original edition” of a textual tradition or at least concerned about weeding through and identifying some of the more obvious errors in whatever text we want to use (e.g., the Leningrad Codex), then we will need to do some textual criticism (or rely on the textual criticism of others). We will need to identify and sort through the variants and make some decisions on which reading is better. Even if you have no theological or ideological reasons for wanting to identify the “original text,” it is pretty much a practical necessity if you are going to do any translation or exposition as you will have to decide what text you are translating or expounding.

Implications and Conclusions

The simple fact that there are no error-free manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible troubles some people — typically those from more conservative backgrounds who hold a very high view of Scripture. But there is no getting around this reality. We have no pristine, error-free, originals of the Hebrew Bible (or the NT for that matter). That being said, one should not over-emphasize the significance of the differences between the manuscripts we do have.

First, a quick count of the textual variants in BHS shows that on average for every ten words there is a textual note — and many of these can be discounted. That leaves about 90% of the text with no variants. Because of the nature of textual criticism, however, the focus is on the relatively few variants, not on the many uncontested readings, and so it is easy to lose our sense of proportion.

Second, most of the textual variants are relatively insignificant. Most text critical work is boring because the differences are inconsequential (Al Pietersma has a saying about text critical work that reflects the tedious nature of the enterprise: bean by bean). Many variants are easily identified and corrected. A slip in the transcriptional process is normally subject to human correction. In the same way we correct errors in reading any book or manuscript, we can correct biblical texts. Even the great variety of text types attested in the DSS underscore their genetic relationships. Shemaryahu Talmon notes:

The scope of variation within all these textual traditions is relatively restricted. Major divergences which intrinsically affect the sense are extremely rare. A collation of variants extant, based on the synoptic study of the material available, either by a comparison of parallel passages within one Version, or of the major Versions with each other, results in the conclusion that the ancient authors, compilers, tradents and scribes enjoyed what may be termed a controlled freedom of textual variation (“Textual Study of the Bible — A New Outlook,” Qumran and the History of the Biblical Text [Harvard University Press, 1975] 326).

For those Christians who may be troubled by the textual variety surrounding the Hebrew Bible, all I will say is don’t worry! The same kind of variants and plurality we find in the DSS today, were around during the time of Jesus and the apostles — and they did not hesitate to rely on the authority of Scripture. Their citations agree with the varying text types found we find in the DSS. The record of Stephen’s speech before the Sanhedrin in Acts 7 employs a pre-Samaritan text, while the NT often quotes from the Septuagint textual tradition.

While the textual reality of the Hebrew Bible is not a hindrance to maintaining a high view of Scripture, it may have some implications to how we understand and formulate our view of Scripture, but I will leave those discussions for a later time. (In this regard you may want to check out Chris Heard’s post “What’s Wrong with Inerrancy.“)

Here is the information from the German Bible Society:

Here is the information from the German Bible Society: When I was in Toronto for CSBS, I went to the annual Pietersma picnic and caught up with the likes of Claude Cox, Tony Michael, Cameron Boyd-Taylor, Paul McLean, Wade White, and, of course, Al Pietersma. We talked briefly about a recent volume on the Septuagint in which Pietersma, Boyd-Taylor, and White contributed:

When I was in Toronto for CSBS, I went to the annual Pietersma picnic and caught up with the likes of Claude Cox, Tony Michael, Cameron Boyd-Taylor, Paul McLean, Wade White, and, of course, Al Pietersma. We talked briefly about a recent volume on the Septuagint in which Pietersma, Boyd-Taylor, and White contributed: