Slate has an interesting article by Robert Alter, entitled “Psalm Springs: How I translated the Bible’s most poetic book,” in which discusses his just-released translation of the Psalter:

Slate has an interesting article by Robert Alter, entitled “Psalm Springs: How I translated the Bible’s most poetic book,” in which discusses his just-released translation of the Psalter:

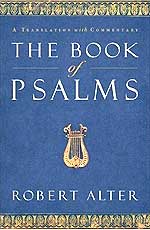

The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary

by Robert Alter

W. W. Norton, 2007

Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com

The article is quite interesting — especially when Alter talks about his translation technique, which could be characterized as very formal (for a discussion of types of translation techniques, see here and here). That is, Alter not only wants his English translation to convey the meaning of the original Hebrew text, he also wants it to convey its structure and form. Thus, if the Hebrew line is composed of three words, then he would try to reproduce that compactness in his translation.

Here is an excerpt from the article:

… The sundry English translations, from Renaissance to contemporary, have in certain ways obscured key strengths of the Psalms. My dissatisfaction with them led me to attempt my own translation.

Two aspects of the Hebrew poems have especially suffered in translation: their powerfully compact rhythms—which, after all, constitute much of the music of the poetry—and the terrific, physical concreteness of the language. The conciseness of biblical poetry derives from the structure of the ancient language: Pronouns are usually omitted because you can tell the pronoun subject from the way the verb is conjugated; possessive pronouns are simply suffixes attached to the nouns; and the verb to be is entirely dispensed with in the present tense. Sometimes, there is simply no way of reproducing this compression in English. In the Hebrew, “The Lord is my shepherd” is just two words, two accents (Yahweh ro’ i). But I, like the translators convened by King James, could see no other way of getting this into workable English.

In many lines, however, a little resourcefulness can produce rhythms resembling the Hebrew’s. The King James version of Psalm 30:9 reads: “What profit is there in my blood, when I go down to the pit?” (The 1611 translators used italics for words merely implied in the Hebrew.) From a rhythmic standpoint, this sounds more like prose than poetry. My version reads: “What profit in my blood,/ in my going down deathward?” This rhythm is virtually identical to the Hebrew, the second half of the line just one syllable more than the original. The alliteration of “down deathward” has no equivalent in the Hebrew, but it helps the rhythmic momentum and compensates for other places (including the first half of this line) where alliterations in the original could not be reproduced.

Let me offer one more example of an effort to emulate the music of the Hebrew. The opening line of Psalm 104, a paean to the grand panorama of creation, was translated in the King James version as “thou art clothed with honour and majesty.” This has a certain poised dignity, though there are too many words and syllables: The Hebrew original has three words, six syllables. And honour doesn’t capture the true significance of the Hebrew hod, which means either grandeur or glory. My version reads: “Glory and grandeur You don.” Here the strong alliteration mirrors a similar effect in the Hebrew (hod/hadar), and the syntactic inversion also follows the Hebrew, reproducing its emphasis on these two terms. Finally, I chose don as part of a general strategy to use single-syllabic words of Anglo-Saxon derivation, and to avoid the potential awkwardness and abstraction of Latinate terms (such as majesty or, elsewhere, transgression).

I have some issues with Alter’s translation technique — though perhaps not so much with his technique, but with his sense of superiority concerning it. I tend to view translation techniques as a tool which produces a variety of types of translations, each useful for different purposes. I have required Alter’s translation of Genesis for my course on the book of Genesis for the very purpose of getting students to read the text in a translation different than what they are used to — and I may use this new translation when I next have to teach the book of Psalms.

One feature of his translation which I find fascinating is the way in which he translates the Hebrew word nefesh (× ×¤×©), a word that is difficult to translate, but which has traditionally been rendered as “soul.” Here is what Alter says about his way of dealing with this word:

Although it may at first disconcert some pious readers, I have rigorously excluded the word soul from my version of Psalms. In the original biblical language, there is no split between body and soul and no notion of a soul surviving the body. Rather, nefesh means life-breath (one hears the breathing in the sound of the Hebrew word)—the God-given vital force that passes in through the nostrils and down into the lungs, animating the body. By extension, it means life. “My nefesh” is also an intensive way of saying “I” (which I sometimes translate as “my whole being” or “my being”). Because the throat is a passageway for the breath, this same word can also mean, by metonymy, throat or neck.

I think this is a wonderful idea considering the amount of confusion there is about the biblical teaching on the nature of the humanity. While there are a few passages in the Hebrew Bible that may give a glimpse of some sort of life after death, in the Hebrew Bible humanity is presented as a radical unity.

At any rate, I encourage you to take a look at the article in full and check out his translation for yourself, as well as his other translations of the Hebrew Bible:

- The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary (Norton, 2004; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com)

- Genesis: Translation and Commentary (Norton, 1997; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com)

- The David Story: A Translation with Commentary of 1 and 2 Samuel (Norton, 2000; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com)

(HT Tim Willson)