As it turned out, Loren Rosson III at the busybody had posted some of his thoughts on Palindromes (the movie, not the trope) here and most recently here. In his original post Loren linked to Ebert’s collection of excerpts from other reviews. I found these to be quite reassuring — evidently I was not alone in my reactions to the film! (See my original post here).

I did a bit more searching and found that Peter Chattaway had also blogged on the movie here and here. Peter thought that the film was a bit tilted towards the pro-choice side of things, though I’m not so sure. I found this series of dialogue quite damming to the pro-choice side:

- Mom: But really, be reasonable, the baby has got to go. What happens if it turns out deformed, if it’s missing a leg, or an arm, or a nose, or an eye? Or if it is brain-damaged or mentally retarded. Children of very young mothers often turn out that way… and then what? And ten you’re stuck, your life is ruined forever, you end up on food stamps alone.

- Aviva: But it’s my baby!

- Mom: But it’s not a baby, not yet, really, it’s just… it’s like it’s just a tumour.

- Aviva: I’m keeping it.

- Mom: No you’re not!

- Aviva: Yes I am.

- Mom: You have the baby you find another home!

- Aviva: You can’t take my baby away from me!

- Mom: It’s too late, I’ve already made the appointment.

This next conversation — really more of a monologue since Aviva doesn’t say anything but nonchalantly eats her sandwich– is even more chilling, IMHO:

- Mom: When you were just a little girl, around three or four, I was pregnant. And at first I was all happy and excited. A new friend for you I thought, a little baby brother. I used to think I’d call him “Henry” after my grandfather Heinric who never cared about money. But then our father and I had a long talk and I begun to realize that there were other things to think about. Your father was out of work, my paintings weren’t selling (I was blocked), I started smoking again, there were bills, a mortgage, a lawsuit. If I’d had another child I wouldn’t have been able to give you all that I had. The time we spend together, just you and me, and the little things your father and I pick up for you. The N’Sync tickets, Gap account,… Ben and Jerry’s. We couldn’t have afforded it. It would have been too much of a strain and we all would have been miserable.

In the context of the movie you realize Aviva doesn’t have any choice (it’s her parent’s choice), and it’s the Christian family who does accept into their family the “deformed” and “brain damaged.” Of course, like I said, no one comes out unscathed. The Christian family is also played so over the top that it’s ridiculous (and the father is complicit in the killing of an abortionist).

Loren also suggests a connection with the book of Ecclesiastes. I think it would be quite interesting to flesh out this connection — especially considering that Norbert Lohfink argues that Qohelet borrowed heavily from Greek thought and structured his book as a palindrome! (See his Qoheleth: A Continental Commentary [Fortress, 2003; Amazon.ca or Amazon.com]). The deterministic view expressed in the film fits well with Ecclesiastes, as does the frequent juxtaposition of opposing viewpoints with no easy resolution. Finally, Qohelet’s overarching assessment that everything is hebel — absurd, meaningless — conforms well with the film.

Take, for instance, this piece dialogue near the end of the film between Aviva and her cousin Mark Wiener, who has been accused (unjustly?) of child molestation:

- Mark: People always end up the way they started out. No one ever changes. They think they do, but they don’t…. There’s no freewill. I mean I have no choice but to choose as I choose, to do as I do, to live as I live. Ultimately we’re all just robots programmed arbitrarily by nature’s genetic code.

- Aviva: Isn’t there any hope?

- Mark: For what? We hope or despair because of how we’ve been programmed. Genes and randomness — that’s all there is and none of it matters…

- Aviva: What if you’re wrong? What if there’s a God?

- Mark: Then that makes me feel better.

It sounds like Mark has been reading Ecclesiastes! Of course one of the keys to interpreting Ecclesiastes is to read right up until the end:

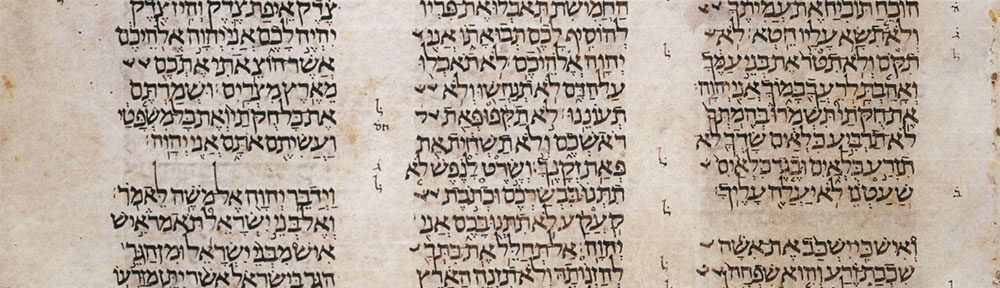

The end of the matter; all has been heard. Fear God, and keep his commandments for that is the whole duty of everyone. For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every secret thing, whether good or evil (Eccl 12:13-14).

For those interested in exploring the connection between Ecclesiastes and popular film, I encourage you to pick up Robert K. Johnston’s Useless Beauty: Ecclesiastes through the Lens of Contemporary Film (Baker, 2004; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com).

At any rate, as you can probably tell, this movie gives you much to think about, and for that reason alone it is worth watching — but be warned, even though this movie has no profanity or nudity, it is nonetheless not for the faint of heart or easily offended.

A little known palindrome fact: the comedy singer “Weird Al” Yankovic produced a song entirely of rhyming palindromes on his 2003 album Poodle Hat, called “Bob.”