Tim Bulkeley over at SansBlog asked me to expand my analysis of the newly-discovered fragments of Leviticus by describing a bit of the processes involved in identifying and reconstructing the fragments. I thought that I would entertain his request, though I should note up front that I am by no means an expert in this! My interest in the reconstruction of Dead Sea Scroll fragments is a tangent of my work on the so-called Qumran Psalms scrolls for my dissertation that combines my interest in computer technology and really old stuff!

At any rate, I thought I would outline some of the steps in identifying, reconstructing, and analyzing scroll fragments using the Leviticus fragments by way of illustration. (Since I am not an expert at this, I would love to get feedback from those who are!)

STEP 1: Identification

The first (obvious) step in reconstructing a fragment is figuring out what it is a fragment from! This is done by identifying some of the extant letters and words on the fragment and then performing some searches with various computer software to see if you can locate the text.

Image Adjustment

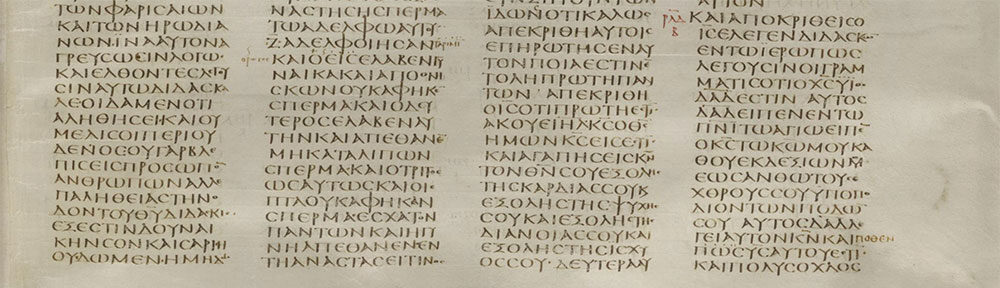

Before you can identify some of the letters it may be necessary to make some adjustments to the image to bring the letters into sharper relief or even to make the fragment readable in the first place! Note that I am dealing with working with images and not the actual original fragments. This is preferable in most cases as the originals may not be readable and (more significantly) they are likely not accessible! High resolution images may be obtained from various sources, including the Ancient Biblical Manuscript Center at Claremont.

I prefer to do my work on the images with Adobe Photoshop. Within Photoshop you can adjust the input and output levels (using the histogram feature), brightness/contrast, among other things to make the text more readable. While the low resolution images of the Leviticus fragments I tracked down on the web are pretty clear, they can be made even clearer by adjusting them slightly:

The adjusted image is a bit easier to read. At times the difference may be dramatic. Compare the two images of PAM 42.141 where the text becomes readable only by adjusting the original image:

Identifying the Text

Once you can read the fragment — or at least some of the fragment — then you can start the process of identification. This is a bit easier for biblical fragments since there are a number of excellent databases of the Hebrew Bible to begin the identification process. I prefer to use Accordance Bible Software for my searches, though Logos Bible Software and BibleWorks, among others, are more than adequate (see my Software for Biblical Studies Pages for descriptions of these and other biblical studies software programs).

With the small Leviticus fragment I did a search for כל־נדריכם “all your votive offerings” which is easily readable in the first line of the fragment. This search discovers that Lev 23:38 is the only occurrence of this phrase in the Hebrew Bible (I also searched a Qumran database with no matches). At that point the rest of the readable words can be checked in the context to see if you have found a match. In the case of the small Leviticus fragment, the other readable words from it easily fit the context of Lev 23:38-39. The same was the case for the larger Leviticus fragment (it is actually two fragments that have been joined), since there were quite a few readable words to make a certain identification with Lev 23:40-44; 24:16-18. You often don’t have as much to work with, however! In my work on 1Q12 (1QPsc) I identified a fragment 8 based on two readable letters and portions of another letter (see my Proposed Reconstruction).

STEP 2: Reconstruction

Once you have the text identified, the next step is to reconstruct it so that you may confirm your identification and ascertain other things about the fragment such as its original size. In order to do this I use Microsoft Word and/or Photoshop (I have also used Quark XPress for this step) to see how the text lines up with the fragment. So, for example, with the smaller Leviticus fragment I imported Hebrew text of Lev 23:38-39 (without pointing) into Word and then adjusted the right-hand margin until the text lined up in accordance with the fragment. In the case of the smaller fragment, the text lined up quite nicely, producing lines of ca. 22-28 letterspaces:

My reconstruction shows the extant Leviticus 23:38 and 39 in bold black type with an outline of the fragment placement. The space at the top of the fragment preserves part of the top margin of the scroll (the dark spot near the top of the fragment is likely an ink dot or a blemish on the leather).

Here is a translation with the extant words in bold:

38 …and apart from all your votive offerings, and apart from all your freewill offerings, which you give to the Lord. 39 Now, the fifteenth day of the seventh month, when you have gathered in the produce of the land, you shall keep the festival of the Lord, lasting seven days; a complete rest on the first day, and a complete rest on the eighth day.

For the larger fragment, it was a bit more complicated since I was dealing with two columns. But once again, the text lined up very nicely producing lines of ca. 22-28 letterspaces for the right column and 20-25 for the left column, and a column height of ca. 33 lines.

Here is an image of the large fragment:

Here is my reconstruction of the columns:

My reconstruction shows the extant Leviticus 23:40-44 (middle of the right column) and 24:16-18 (left column) in bold black type with an outline of the fragment placement. Note that the smaller fragment also nicely fits at the top of the right column.

The one variant from the

MT (as represented by

BHS) is the plene spelling of בסכת at the end of verse 42 (the vav is in red). (click for larger image)

Here is a translation with the extant words in bold:

38 …and apart from all your votive offerings, and apart from all your freewill offerings, which you give to the Lord. 39 Now, the fifteenth day of the seventh month, when you have gathered in the produce of the land, you shall keep the festival of the Lord, lasting seven days; a complete rest on the first day, and a complete rest on the eighth day.

…

41You shall keep it as a festival to the Lord seven days in the year; you shall keep it in the seventh month as a statute forever throughout your generations. 42 You shall live in booths for seven days; all that are citizens in Israel shall live in booths, 43 so that your generations may know that I made the people of Israel live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God. 44 Thus Moses declared to the people of Israel the appointed festivals of the Lord.

…

16One who blasphemes the name of the Lord shall be put to death; the whole congregation shall stone the blasphemer. Aliens as well as citizens, when they blaspheme the Name, shall be put to death. 17 Anyone who kills a human being shall be put to death. 18 Anyone who kills an animal shall make restitution for it, life for life.

N.B. For a detailed reconstruction, you would have to do much more than just count letters. You would need to consider the widths of different letters in the scroll’s script. For example, even on these fragments it is clear that the

י yods and

ו vavs take much less space than the

שׂ sins and

ב bets. For more detail on calculating letter widths and scroll reconstruction in general, see Edward D. Herbert,

Reconstructing Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Method Applied to the Reconstruction of 4QSama (Brill, 1997;

Buy from Amazon.ca –

Buy from Amazon.com). You would also need to check to see if these verses are extant in any other scrolls from Qumran; in this case you would want to double check your text with 4QLev

b (as it turns out these particular words are not found in 1QLev

b).

STEP 3: Description

The third step is to describe your findings and if you were working with the original fragments, you would also provide a physical description. In this case, if the reconstruction is correct, the larger fragment would have been part of a scroll that was quite large. Based on this height and the number of lines per column, the scroll itself would have been on the large size for scrolls found at Qumran and likely contained the complete book of Leviticus, if not the entire Torah/Pentateuch (see Emanuel Tov, “Scribal Practices and the Physical Aspects of the Dead Sea Scrolls” in

The Bible as Book: The Manuscript Tradition [John L. Sharpe and Kimberly Van Kampen, eds.; 1998] 9-33;

Buy from Amazon.ca –

Buy from Amazon.com).

The nature and type of the leather would also have to be ascertained. While one news report identified the material as “deer hide,” most other authentic scrolls were made from the skins of sheep and goats. While the fragments were not tested, Eshel himself was pretty sure that they were either goat or sheep skin.

An examination of the paleography (the style of writing) is consistent with post-Herodian scripts (end of the first century C.E.), including other scrolls from the Bar Kokhba era, such as the Psalms scroll from the Cave of Letters.

The fragments do not give us much in terms of variant readings. The fragments follow the Masoretic text with one exception: at the end of v. 42 the larger fragment has בסכות instead of בסכת, both “booths” (indicated in red type on the larger reconstruction). This is a minor spelling difference, much like the difference between the Canadian spelling of “honour” and the American “honor.” (The fact that the Samaritan Pentateuch also reads בסכות is inconsenquential as it consistently uses the plene spelling throughout).

Conclusions

Reconstructing scrolls with biblical studies software and imaging programs takes a considerable amount of work. I personally find the work interesting (even fascinating), which explains why I bothered to write up this analysis! What I find amazing is how the first generation of scroll scholars did so much ground-breaking work without this technology!

In regards to the two Leviticus fragments, my hunch is that they are authentic. If not, then my hat goes off to the person or persons who produced such fine forgeries!

I had the absolute privilege of interviewing Professor Hanan Eshel earlier today for an article I am writing for a Canadian national newspaper (ChristianWeek). While I will blog a fuller summary in the near future once I go through the interview again (and will probably blog a transcript of the entire interview once the story is published), I wanted to note some highlights so as to clarify some misperceptions and perhaps correct some of the speculation surrounding this amazing discovery:

I had the absolute privilege of interviewing Professor Hanan Eshel earlier today for an article I am writing for a Canadian national newspaper (ChristianWeek). While I will blog a fuller summary in the near future once I go through the interview again (and will probably blog a transcript of the entire interview once the story is published), I wanted to note some highlights so as to clarify some misperceptions and perhaps correct some of the speculation surrounding this amazing discovery: