The appearance of “Satan” in virtually all English translations of the book of Job befuddles me since it is very clear that Satan was never in the book of Job to begin with! While almost every English translation of the book of Job will refer to “Satan” in the first couple chapters of the book, there is scholarly consensus that this is certainly not what the Hebrew original is referring to!

The appearance of “Satan” in virtually all English translations of the book of Job befuddles me since it is very clear that Satan was never in the book of Job to begin with! While almost every English translation of the book of Job will refer to “Satan” in the first couple chapters of the book, there is scholarly consensus that this is certainly not what the Hebrew original is referring to!

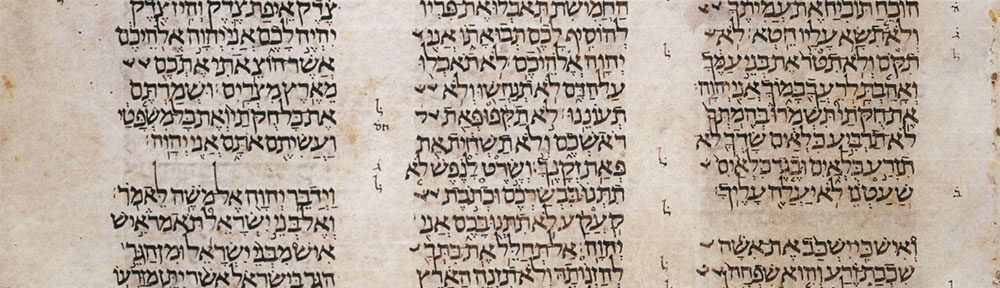

In the prose prologue to the book of Job we are introduced to “the satan” (השטן) who is among the “sons of Elohim” (בני האלהים) (1:6). It is pretty clear that this passage isn’t referring to “Satan” (i.e., the king of demons) since the Hebrew noun “satan” has a definite article. The biblical text refers to “the satan”, not “Satan.” Personal names in Hebrew (as in English) do not take the definite article. I don’t go around referring to myself as “The Tyler” — and if I did, people would think I was weirder than they already think I am.

In the Hebrew Bible, the noun “satan” (שטן) occurs 27x in the Hebrew Bible, fourteen of which are found in the first two chapters of the book of Job. Of the remaining thirteen times, seven instances occur with clear reference to a human adversary. Take, for example these passages from the NRSV:

But David said, “What have I to do with you, you sons of Zeruiah, that you should today become an adversary [satan] to me? Shall anyone be put to death in Israel this day? For do I not know that I am this day king over Israel?” (2Sam 19:22)

But now the Lord my God has given me [Solomon] rest on every side; there is neither adversary [satan] nor misfortune (1Kings 5:4).

Then the Lord raised up an adversary [satan] against Solomon, Hadad the Edomite; he was of the royal house in Edom (1Kings 11:14).

Other examples of satan referring to human adversaries include 1 Sam 29:4; 1Kgs 11:23, 25; and Ps 109:6. The other five occurrences appear to refer to some sort of celestial or angelic adversary. The “Angel of Yahweh” (מלאך יהוה) is referred to as “an adversary” (satan) to Balaam in Num 22:22 and 23, while the book of Zechariah mentions “an adversary” that accuses the High Priest Jonathan in the presence of the angel of Yahweh (Zech 3:1, 2 [2x]). Like the passages in Job, virtually all English translations render “the satan” (השטן) in Zechariah as “Satan” (see KJV, RSV, KRSV, NIV, NASB, etc.) even though the articular noun is not being used as a personal name. The one exception to this longstanding traditional translation is found in the NJPS where it translates “ha-satan” in Zechariah as “the Accuser” and in Job as “the Adversary.” The usage of the related verb stn (שטן), “be hostile to, accuse,” parallels the noun, though of its six occurrences, only one refers to the work of a celestial being (Zech 3:1); the others are actions attributed to human adversaries (Pss 38:21; 71:13; 109:4, 20, 29).

The only passage in the entire Hebrew Bible where satan may refer to “Satan” as the fallen leader of demonic forces is 1 Chronicles 21:1, where satan (significantly without the definite article) incites King David to take an ill-fated census. This passage is also an interpretive crux historiographically, since it parallels 2Sam 24:1 where Yahweh incited David to take the census. Evidently, the Chronicler had theological problems with Yahweh inciting the census and then punishing David for taking it, and therefore made the change in his text for theological reasons (alternatively, the Chronicler’s Hebrew text of 2Samuel may have already contained the change, since the evidence of 4QSam-a suggests the Chronicler may have had a different text). While I still lean towards the traditional understanding of this passage as referring to “Satan,” I should note that most recent commentators have moved away from this understanding and have proposed a human adversary or an angelic adversary akin to Job and Zechariah.

When we turn to the book of Job, then, we do not find the full-blown figure of Satan. Instead, we find a celestial being who is part of Yahweh’s divine council, i.e., one of the “sons of Elohim”, who functions in the book of Job as a heavenly adversary. More specifically, in the book of Job, the satan fills the role of a prosecuting attorney. In this respect, the NJPS translation as “the Adversary” is perhaps the best possible.

The development of “the satan” into “Satan,” i.e., the evil arch-enemy of God, seems to have occurred primarily after the Hebrew Bible, perhaps under the influence of Persian Zoroastrianism (although this is debated). Whatever the influence, when we turn to Second Temple Jewish literature such as 1 Enoch or the DSS, we find a far more developed angelology/demonology. This is continued into the New Testament where you find a full-blown (albeit not systematic) angelology and demonology.

What I find interesting is why virtually every modern English translation continues to render “the satan” in the book of Job as “Satan,” despite the fact it has a long historical pedigree (facilitated no doubt by the LXX, Targums, and Vulgate, among others). True, the NRSV (as well as a few other English translations) has a footnote providing an alternative understanding (“the Accuser; Heb ha-satan“), shouldn’t it really be the other way around? While it doesn’t surprise me that the more conservative Christian translations have kept the traditional rendering as “Satan,” it does surprise me that translations such as the NRSV has perpetuated such a traditional understanding.

Now don’t get me wrong, I am not saying that the figure of “the satan” in the book of Job is not sinister; he does question the motives behind Job’s fear of Yahweh, but he is not the “Satan” found in the New Testament. There is significant theological development from the time of the Old Testament through the Second Temple period to the New Testament and beyond. But in our translations of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament I think it is very important to translate (as mush is possible) the original meaning of the text, rather than a later theological interpretations/developments (and yes, I recognize all of the pitfalls surrounding the language of “original meaning,” but I think you know what I mean). In the same way translations shouldn’t import the notion of the Trinity into the Hebrew Bible, nor should they import a more developed demonology into the Old Testament.

If this post as piqued your interest, you may be interested in some of the following books:

- Powers of Evil: A Biblical Study of Satan and Demons by Sydney H. T. Page (Baker, 1994; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com ). [This is a well-researched and well-balanced biblical-theological examination from a somewhat conservative Christian perspective from my colleague at Taylor Seminary]

- An Adversary in Heaven: Satan in the Hebrew Bible by Peggy L. Day (Harvard Semitic Monographs; Scholars Press, 1998; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com). [This is an academic study of the satan in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament.]

- The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth by Neil Forsyth (Princeton University Press, 1989; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com). [This is an engaging academic look at the development of the figure of Satan in connection with the ANE combat myth]

- Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible edited by Karel van der Toorn, et al (2nd edition; Eerdmans, 1999; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com). [This is a comprehensive academic reference dictionary that will give more more than you ever wanted to know about angels, demons, and deities]

For recommended commentaries on the book of Job, see my Old Testament Commentary Survey. If you are interested in the further development of the figure of Satan, see Phil Harland’s excellent series of posts on the “History of Satan.”