The last few posts in this series discussed some of the major witnesses to the text of the Old Testament; this post will bring them together and describe a bit of the history of the transmission of the Hebrew Bible.

This is the sixth post in a series on the textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. Other posts include:

All posts in this series may be viewed here.

The history of the text of the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible can be divided into five periods on the basis of the kinds evidence available:

- from the time of composition to mid-third century BCE, for which no extant texts are available;

- from mid-third century BCE to end of first century CE, when the variety of types of texts found at Qumran are attested;

- from the end of the first century CE to the end of the tenth century, that is, from the survival of proto-MT alone to the work of Aaron Ben Asher;

- from the end of the tenth century to the sixteenth century, attested by the hundreds of medieval Masoretic manuscripts; and

- from sixteenth century to the present, the time of printed Hebrew editions of the Bible.

Arguably, the discovery of the DSS has so revolutionized our understanding of the text, that it ought to be marked off as a new era. Harold Scanlin, United Bible Society translation advisor, pretty much argued as much when he said: “These changes [in our understanding of the history of the text] are at least as significant as the nineteenth century revolution in New Testament textual criticism, culminating in the work of Westcott and Hort” (Harold P. Scanlin, “The Presuppositions of HOTTP and the Translator,” BT 43 [1992] 102).

For the purposes of these posts, I have treated the last three periods sufficiently in my discussion of the MT, therefore I will focus here exclusively on the first two periods.

From Composition to Mid-Third Century BCE

Discussion of this early period is necessarily conjectural since there are not extant manuscripts from this era. While a few scholars posit a very late date for the writing of many biblical books, based on a number of lines of evidence it is plausible that the majority of biblical books were composed by the mid- to late-third century BCE. (Some of the evidence includes early versions like the Septuagint, while other evidence is based more on the signs of development apparent — at least to me! — in the biblical text, as well as the intertextuality between many biblical books.) While perhaps this warrants a future post, suffice it to say that I am assuming most — but not necessarily all — biblical books were composed during this period.

During this period, it can be inferred both from extra-biblical and biblical sources a tendency both to preserve and to revise the text.

1. The Tendency to Preserve the Text.

There are three factors which demonstrate the early scribal tendency to preserve the text. First, the very fact that the biblical books persistently survived the most deleterious conditions throughout a more or less long history until the extant manuscripts demonstrates that indefatigable scribes insisted on its preservation. The books were written on highly perishable papyrus and animal skins in the relatively damp, hostile climate of Palestine. The prospects for their survival were most uncertain in a land that served as a bridge for armies in unceasing contention between the continents of Asia and Africa — a land whose people were the object of plunderers in their early history and of captors in their later history. That no other purported Israelite writings, such as the Book of Yashar (e.g., 2 Sam 1:18) or the Annals of the Kings (e.g., 2 Chron 16:11), survive from this period indirectly suggests the determination of the scribes to preserve the biblical books. Of course, I am assuming that there may be something behind many of these references to other writings, instead of seeing them as rhetorical devices only serving to give some verisimilitude to the writings.

Second, the OT itself (cf. Deut 4:2; 12:32; Josh 1:7; 24:25, 26; 1 Sam 10:25; Ps 18:30; Prov 30:6-7; Eccl 12:12) and relevant literature of the ancient Near East show that at the time of the OT’s composition a mindset favouring canonicity existed. For example, the famous Code of Hammurabi (ca. 1750 BCE) and the Hittite treaties of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1400-1200 BCE), closely resembling Deuteronomy, call down imprecations on anyone who tampers with one word in them. This mindset must have fostered a concern for care and accuracy in transmitting the sacred writings.

2. The Tendency to Revise the Text.

On the other hand, both biblical and extra-biblical data show a tendency to revise the text during this period. This can be demonstrated by four strands of evidence. First, the post-exilic book, Ezra-Nehemiah, states that as Ezra read from the Book of the Law of God, he made it clear and gave the meaning so that the people could understand what was being read (Neh 8:8), implying he modernized and explained the earlier text.

Second, the many differences between synoptic portions of the Hebrew Bible strongly suggest that those entrusted with the responsibility of teaching the Bible felt free to revise the texts (Compare, for instance, 2 Sam 22 = Ps 18; 2 Kgs 18:13-20:19 = Isa 36-39; 2 Kgs 24:18-25:30 = Jer 52; Isa 2:2-4 = Mic 4:1-3; Ps 14 = 53; 40:14-18 = 70; 57:8-12 = 108:2-6; 60:7-14 = 107:14; Ps 96 = 1 Chr 16:23-33; Ps 106:1, 47-48). The differences between synoptic portions resemble the same sort of variations found in the Qumran scrolls, suggesting that scribes, before the extant texts, felt free to revise the text within the similar restraints attested in the Qumran scrolls as noted by scholars.

Third, this effort to clarify and update the text was entirely in keeping with textual practices in the ancient Near East. Albright said: “A principle which must never be lost sight of in dealing with documents of the ancient Near East is that instead of leaving obvious archaisms in spelling and grammar, the scribes generally revised ancient literary and other documents periodically.”

Finally, the book of Chronicles in its synoptic parallels with the pre-Samaritan Torah and with the MT’s Former Prophets exhibits the same kinds of revisions as found in the Qumran scrolls, reflecting the early revision of texts. In short, some biblical texts were being conserved and revised at the same time others were being composed.

3. Kinds of Revisions.

From ancient inscriptions and comparative Semitic grammar we can plausibly trace the development of the biblical text’s script and grammar. From epigraphic evidence it appears that in its earliest stage, the text was written in the Proto-Canaanite alphabet, a pictographic alphabet (see my post on Serabit el-Khadem for more about the origins of the alphabet). This script later developed into an angular, pre-exilic Hebrew script, sometimes called Phoenician. At about 1100 BCE short vowels, indicating case and tense, were dropped (See Waltke & O’Connor, Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax [Eisenbrauns, 1990] § 8.1c, 29.4j). During the same period matres lectiones (“mothers of reading”, i.e., vowel letters) were gradually added to the text.

From Mid-Third Century BCE to Late First Century CE

From ca. 400 BCE until the destruction of Second Temple in 70 CE, there also was a tendency to preserve and revise the text, as attested by the DSS and by other Jewish literature from this period.

1. The Tendency to Preserve the Text.

Talmudic notices, calling for a careful preservation of the Hebrew Scriptures, are backed up by the discoveries in the Judean desert. The preservation of the proto-MT reflects its antiquity and preservation. In addition, the para-textual scribal elements attested in the MT about the uncertainty of a few readings, such as inverted nuns (thought to mark verses thought to have been transposed) and other extraordinary points, probably go back to this period and so show an early concern for the text’s preservation.

2. Tendency to Revise the Text.

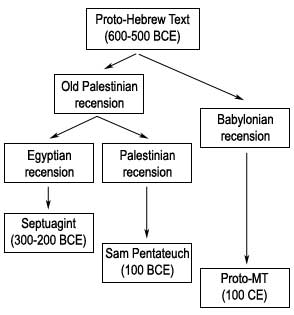

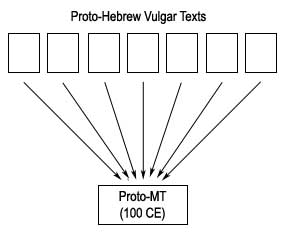

On the other hand, the variant text types attested among the Qumran scrolls unambiguously show that the proto-MT, the pre-Samaritan, and the Septuagintal texts continued to be copied during this period and that those of the “Qumran practice,” and possibly of the non-aligned texts, arose at this time. These variants also find agreement in Jewish literature originating during the time in question, such as the Book of Jubilees (either late or early post-exilic) and the NT (ca. 50-90 CE).

As I have argued, at the end of this period the rabbis stabilized the text by preserving only the dominant proto-Masoretic text type. The fall of the Second Temple, the Jews debate with Christians, and Hillel’s rules of hermeneutics, all called for a stabilized text. And socio-political realities led to dominance of the early rabbis and their proto-Masoretic text.

3. Kinds of Revisions.

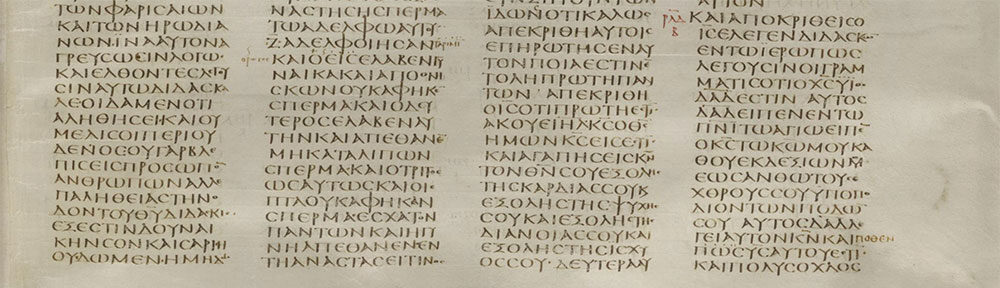

Sometime after the Exile the Jews switched from the pre-exilic, angular script to the post-exilic, Aramaic script, also called square script because most of the letters are written within an imaginary square frame (It should be noted, however, that some DSS of varying text types were still written in the angular paleo-Hebrew script). With the new script came five final letter forms, which helped the division of words. Here is a chart from GKC with the various semitic alphabets and scripts (click to enlarge):

In addition, matres lectiones continued to be added to the text and spellings were updated (orthography). These changes are seen (in varying degrees) in the variety of different texts types extant in the DSS. The pre-Samaritan text, for example, exhibits linguistic modernization, expansions, interpolations, and exegetical smoothing, as does the proto-MT.

Another significant revision from this period is the safeguarding of the tetragrammaton (YHWH) by occasionally substituting forms in the consonantal text (this is also seen in the translation of YHWH by “Lord” in the LXX).

Conclusions

As a result of this transmission history (only briefly sketched here), by the end of the first century CE, the biblical text had undergone a series of intentional and unintentional changes and a number of varying text types emerged. The relationship between these text types is rarely simple to discern, and some books appeared to have more than one final form (or at least they circulated in more than one version).

I have not been posting the weekly

I have not been posting the weekly