Claude Mariottini, in a post on the “Old Testament and Baldness” linked to an article from the Mail & Guardian by Nicholas Lezard on The Horror of Going Bald. As one who at forty years still has a thick, lush, head of hair, such articles don’t concern me. The article did make reference, however, to one of my favourite(?) disturbing(!) Bible stories: the story in 2Kings 2:23-25 where Elisha calls a curse down on some children who are taunting his baldness. Here is the quote from the news article:

Baldness is a curse that demands all the fortitude at one’s disposal. It is a curse not only because it looks as though something biblical has happened to your head — it is also the way it is seen as comical, both as a fact, and as an occasion for comical reaction. The Moabites, reckless high-livers who made too many incursions into Israeli territory in the Old Testament, were afflicted, according to Jeremiah, by baldness. At one point Elisha is mocked by children (“There came forth little children out of the city, and mocked him, and said unto him, Go up, thou bald head; go up, thou bald headâ€?). Later God sends a couple of she-bears from the woods and they tear 42 of the Moabites to pieces.

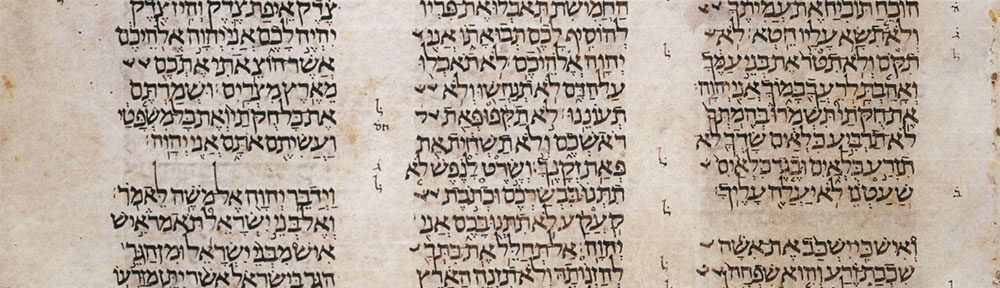

What I thought was odd, was the reference to the mauled children as “Moabites.” Now, perhaps I am wrong, but the context is pretty clear that the children were from Bethel, an Israelite town. While Bethel may have shifted in political ownership between the tribe of Benjamin and Ephraim, it was never Moabite. Here is the biblical passage in question:

23 He [Elisha] went up from there to Bethel; and while he was going up on the way, some small boys came out of the city and jeered at him, saying, “Go away, baldhead! Go away, baldhead!� 24 When he turned around and saw them, he cursed them in the name of the LORD. Then two she-bears came out of the woods and mauled forty-two of the boys. (NRSV)

So the 42 “small boys” mauled by the bears were fellow Israelites. The biggest question surrounding this passage is “what do we make of it?” There are a number of disturbing passages in the Hebrew Bible. Many of them are horrifying illustrations of human depravity (e.g., Judges 19), which don’t necessarily reflect poorly on the deity of the Bible. But in this passage, it is God who is the implied agent behind the bears’ actions. Elisha curses the young boys “in the name of Yahweh” and then the bears go about their business.

The problematic nature of this passage has led to much exegetical gymnastics by commentators trying to make this passage less morally offensive. Many suppose the boys taunted Elisha at the instigation of their parents and that the who event was to be a prophetic warning to the inhabitants of Bethel. Others suggest the “young boys” were teenage ruffians, though the Hebrew makes this unlikely (while × ×¢×¨ “lad” “boy” by itself may suggest adolecents, it is qualified by קטן “small,” which suggest they were on the younger end of things). Still others suggest that by taunting him to lit. “go up” they are wishing for his death (or at least his departure from this earth, perhaps similar to Elijah’s). Most of the explanations focus on the idea that when the boys taunted the prophet of Yahweh, it was tantamount to taunting God himself, and that their mauling is somehow justified. Obviously the adage, “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me” doesn’t apply to prophets! (This to me is the real problem with this passage, no matter how bad these boys were, their judgement sure seems to me to be out of proportion).

Any moral justification aside, God using animals to bring about his judgement is found elsewhere in Kings (1 Kgs 13:20–24 and 20:35–36). This is also akin to other extreme judgements in connection with the violation of the sacred (e.g., the touching of the Ark of the Covenant in 2Sam 6). Perhaps there is something in the many explanations offered about this passage. While this may be the case, I tend to think this is just one of those passages that reveal the dark side of the God of the Bible and it is better to let stand, rather than offer poor explanations to make it more morally palatable.

What do you think?

P.S. The South-Park-esque comic about this passage I mentioned in a previous post may be found here (be warned; the comic is twisted).

Here is the information from the German Bible Society:

Here is the information from the German Bible Society: When I was in Toronto for CSBS, I went to the annual Pietersma picnic and caught up with the likes of Claude Cox, Tony Michael, Cameron Boyd-Taylor, Paul McLean, Wade White, and, of course, Al Pietersma. We talked briefly about a recent volume on the Septuagint in which Pietersma, Boyd-Taylor, and White contributed:

When I was in Toronto for CSBS, I went to the annual Pietersma picnic and caught up with the likes of Claude Cox, Tony Michael, Cameron Boyd-Taylor, Paul McLean, Wade White, and, of course, Al Pietersma. We talked briefly about a recent volume on the Septuagint in which Pietersma, Boyd-Taylor, and White contributed: