I came accross a news article entitled “Rabbinic bias obscures Messianic message of Old Testament, Prof says” (It is also reproduced as “Messianic hope ‘shines’ in Hebrew Bible“). The article reports on Michael Rydelnick, a Jewish studies professor at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, who argues that the Hebrew Bible is biased against Christianity. Here are some extended quotes from the article:

Just as today there are many versions of the Christian Bible — each choosing different words to translate the Scripture for diverse audiences — there were different versions of the Hebrew Bible in the three centuries before Christ, Rydelnick said. However, when Protestant reformers turned away from the Latin Bible of the Roman Catholic Church to re-translate the Old Testament, Rydelnick noted that they accepted a Masoretic version of the Hebrew Bible that had been influenced for centuries by rabbis who wanted to obscure the Messianic message in the Scripture.

….

In fact, centuries ago when the Hebrew scriptures were being consolidated, Jewish scholars agreed they would only include a book in their canon if it carried a theme of Messianic hope, Rydelnick said. In the Middle Ages, however, when Jews were being pressured to convert to Christianity, Jewish scholars began to emphasize King David as the fulfillment of prophecy. The Protestant reformers — and subsequent generations of Christian scholars — based their work on Hebrew texts and commentaries that reflected a bias against Christ, Rydelnick said.

There are a number of assertions in this article which I question, though what I want to focus on is his text-critical practice. The article provides a couple of examples where the MT allegedly obscures such messianic readings. The first example is from Numbers 24:7 where the MT reads as follows:

יִֽזַּל־מַ֙יִם֙ מִדָּ֣לְיָ֔ו וְזַרְע֖וֹ בְּמַ֣יִם רַבִּ֑ים וְיָרֹ֤ם מֵֽאֲגַג֙ מַלְכּ֔וֹ וְתִנַּשֵּׂ֖א מַלְכֻתֽוֹ׃

Water shall flow from his buckets,and his seed shall have abundant water, his king shall be higher than Agag, and his kingdom shall be exalted (NRSV).

Rydelnick reportedly argued that the reference to Agag, the Amalekite king from the time of King Saul (1Samuel 15), has no messianic connotations since it has been fulfilled historically by David. “Other versions of the Hebrew Bible” however, have the word “Gog” instead of “Agag,” and that this “Gog” is, according to Rydelnick, “the end-times enemy of the returning Christ (Revelation 20:8) – a prophecy David could not fulfill.”

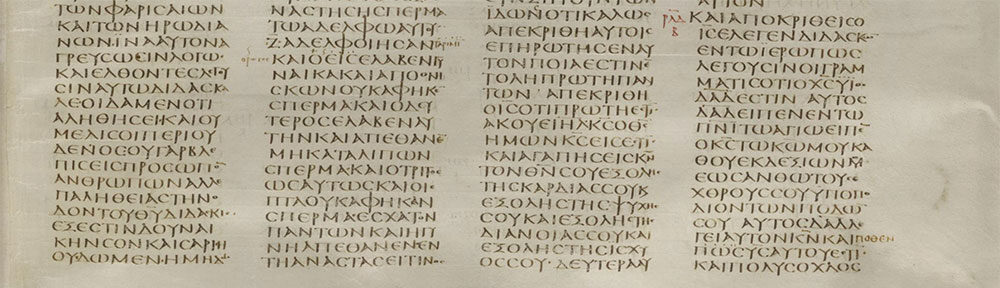

On one level the report is accurate insofar that the Samaritan Pentateuch (which I assume is on of the “other versions of the Hebrew Bible” he refers to) reads מִגּוֹג “…than Gog.” In addition, the LXX and its revisers also have Γωγ “Gog.” What other version of the Hebrew Bible he is referring to is not clear. He may be referring to 4QNumb, though while part of the verse is preserved in fragment 24ii, 27-30, the text is not extant at this precise point. (As an aside, I found it interesting that DJD 12 [see pp. 235-237] reconstructed the text with מגוג, presumably because the rest of the scroll contains slightly more secondary readings in agreement with the Samaritan Pentateuch and LXX, than with the MT. The editor, however, did not feel confident enough to include it in his list of reconstructed variants.)

While the reading “Gog,” the future antagonist of Israel referred to in Ezekiel 38-39, does put a more eschatological spin on the text, a glimpse at older and more conservative commentaries illustrate that the Masoretic text as it stands has provided much fodder for messianic interpretations.

The other passage that is mentioned in the article is Genesis 49:10, where the MT has a difficult reading (which incidentally has been called the “most famous crux interpretum in the entire OT” by Moran in Biblica 39 [1958] 405). The MT reads עד כי־יב×? ש×?ילה which could be translated literally as “until Shiloh comes” (see the NASB, KJV, NKJV). Most modern translations at this point prefer to either re-divide the word and take it as ש×?Ö¶ + לה “which is to him” (as apparently the LXX and other Greek versions take it; see NIV), or repoint it as ש×?Ö·×™ לה “until tribute comes to him” (see NRSV, NJPS, NJB, as well as the Qere). Rydelnick prefers the second option and sees the passage as “a prophecy that was fulfilled in Jesus’ era, when Rome assumed judicial power over Israel (7 A.D.) and the Temple was destroyed (70 A.D.).”

I do not want to enter into the debate on the validity of messianic interpretations of the Hebrew Bible. What I find troubling is the fact the apparent mining of textual variants to find those readings which fit one’s preconceived ideological or theological views. If you wanted to look for variant readings that would lend themselves to messianic interpretations in the various texts and versions of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament you could have a field day. And the result would be a fascinating study of the early interpretation of the Hebrew Bible (see, for example, Joachim Schaper’s Eschatology in the Greek Psalter [Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1995] which attempts to find eschatological and messianic readings in the Greek translation). To use that goal, however, as the basis for determining the best text seems to me questionable. It reminds me of a recent post on the Biblical Studies discussion list where an individual preferred a reading of Ezekiel 34:29 because it supported a messianic reference to Jesus (incidentally, in this case it was the MT’s מַטָּע לְש×?Öµ×? “planting of renown” which supported the messianic interpretation of the text, not the LXX’s φυτὸν εἰÏ?ήνης). In my opinion the MT likely preserves the best text, however, my reasons have nothing to do with its potential messianic interpretation.

To be sure, the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has complicated the picture of the textual transmission of the Hebrew Bible to the degree that textual criticism becomes an even more challenging if not impossible task. That being said, it does not give us warrant to pick and choose readings willy-nilly according to our presuppositions and biases. Instead, it is even more important to study the different texts and versions all the more carefully so as to discern their genetic relationships as well as their tendencies before we employ them to text-critical ends. This is a task to which few are called and perhaps even fewer are gifted.