As mentioned in my previour post on Septuagint Psalm 151 (first installment in my series on Psalm 151 in the Biblical Tradition), the discovery of Hebrew psalms clearly related to the Septuagint Psalm 151 created quite a stir among biblical scholars. Prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Psalm 151 was only know to us from its Greek and Syriac versions. At the beginning of the last century Septuagint scholar Henry B. Swete noted that “there is no evidence that it [Ps 151] ever existed in Hebrew” (Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek [Hendrickson, 1989], p. 253; buy from Amazon.ca | Amazon.com), and in the 1930s Martin Noth “expressed doubts” about a Hebrew original to LXX Psalm 151 in his study of the five Apocryphal psalms and did not bother to provide a Hebrew retroversion of Psalm 151 in that study.

It was not until the discovery among the Dead Sea Scrolls of the so-called “Qumran Psalms Scroll” (11QPs-a or 11Q5; see my Scroll Introduction) that contained two Psalms (Ps 151A and B) that were clearly parallel with the LXX 151, that scholars universally recognized that LXX Psalm 151 had a Hebrew Vorlage (i.e., a Hebrew original), though the precise relationship between LXX Psalm 151 and 11Q5 Psalm 151 remained under debate.

Before we discuss the nature of the relationship between the Greek LXX Psalm 151 and the Hebrew 11Q5 Psalms 151A and 151B, it would do us well to carefully examine the psalms in question. I have already provided a translation of LXX Psalm 151 in my previous post; here I provide a translation of Psalm 151A and B as found in column 28 of 11Q5:

|

11Q5 Ps 151A-B |

11Q5 Ps 151A & B | |

| 3 |

הללויה לדויד בן ישי |

A Hallelujah of David son of Jesse. |

|

קטן הייתי מןאחי |

Smaller was I than my brothers | |

|

וצעיר מבני אבי |

And the youngest of the sons of my father | |

| 4 |

וישימני רועה לצונו |

And he made me shepherd of his flock |

|

ומושל בגדיותיו |

And ruler over his kids | |

|

ידי עשו עוגב |

My hands made a (musical) instrument | |

|

ואצבעותי כנור |

And my fingers a lyre | |

| 5 |

ואשימה ליהוה כבוד |

And I rendered glory to the Lord |

|

אמרתי אני בנפשי |

I said within myself | |

|

ההרים לוא יעדו לו |

The mountains do not witness to him, | |

| 6 |

והגבעות לוא יגידו |

Nor do the hills declare; |

|

עלו֯ העצים את דברי֯ |

The trees have cherished my words | |

|

והצואן את מעשי֯ |

And the flock my works. | |

| 7 |

כי מי יגדי ומי ידבר |

For who can declare and who can speak, |

|

ומי יספר את מעשי֯ אדון |

And who can recount the works of the Lord? | |

|

הכול ראה אלוה |

Everything has God seen, | |

| 8 |

הכול הוא שמע |

everything has he heard, |

|

והוא האזין |

and he has heeded. | |

|

שלח נביאו למושחני |

He sent his prophet to annoint me, | |

| 9 |

את שמואל לגדלני |

Samuel, to make me great |

|

יצאו אחי לקראתו |

My brothers went out to meet him, | |

|

יפי התור ויפי המראה |

Handsome of figure and handsome of appearance | |

|

הגבהים בקומתם |

They were tall of stature | |

| 10 |

היפים בשערם |

Handsome by their hair, |

|

לוא בחר יהוה אלוהים בם |

The Lord God did not choose them. | |

|

וישלח ויקחני מאחר הצואן |

But he sent and took me from behind the flock | |

| 11 |

וימשחני בשמן הקודש |

And annointed me with holy oil, |

|

וישימני נגיד לעמו |

And made me leader to his people | |

| 12 |

ומושל בבני בריתו |

And ruler over the sons of his covenant |

| 13 |

תחלת גב[ו]רה ה[דו]יד משמשחו נביא אלוהים |

At the beginning of [Dav]id’s p[ow]er after the prophet of God had annointed him |

|

אזי רא֯[י]תי פלשתי |

Then I s[a]w a Philistine | |

| 14 |

מחרף ממ[ערכות האיוב] |

Uttering defiances from the r[anks of the enemy]. |

|

אנוכי [ ] את |

I […] ’t […] |

I should note that while the translation is my own, the above reconstruction follows that by the scroll’s editor, James Sanders (which I do not entirely agree with, but I’ll discuss that in another post). The line numbers in the left-hand column are not precise; they reflect the line divisions of the editor. According to Sanders’s reconstruction, Psalm 151B begins in line 13.

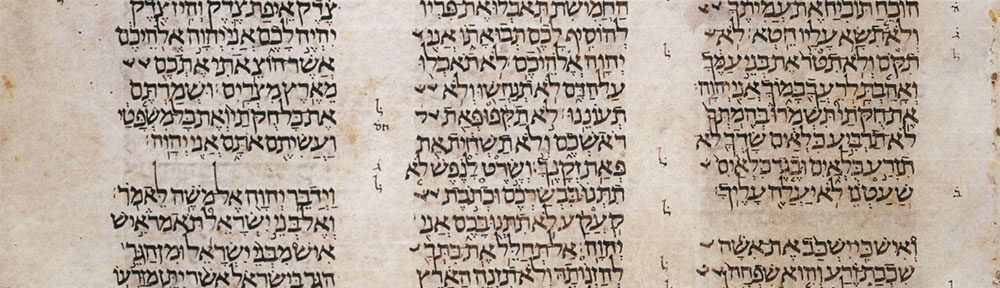

In the actual scroll, the column is laid out as follows:

|

11Q5 Column 28 |

|

|

|

|

|

יהוה העומדים בבית יהוה בלילות שאו ידיכם קודש וברכו |

1 |

|

את שמ יהוה יברככה יהוה מציו[ן] עושה שמים וארץ |

2 |

|

vacat |

|

|

הללויה לדויד בן ישי קטן הייתי מןאחי וצעיר מבני אבי וישימני |

3 |

|

רועה לצונו ומושל בגדיותיו ידי עשו עוגב ואצבעותי כנור |

4 |

|

ואשימה ליהוה כבוד אמרתי אני בנפשי ההרים לוא יעדו |

5 |

|

לו והגבעות לוא יגידו עלו֯ העצים את דברי֯ והצואן את מעשי֯ |

6 |

|

כי מי יגדי ומי ידבר ומי יספר את מעשי֯ אדון הכול ראה אלוה |

7 |

|

הכול הוא שמע והוא האזין שלח נביאו למושחני את שמואל |

8 |

|

לגדלני יצאו אחי לקראתו יפי התור ויפי המראה הגבהים בקומתם |

9 |

|

היפים בשערם לוא בחר יהוה אלוהים בם וישלח ויקחני |

10 |

|

מאחר הצואן וימשחני בשמן הקודש וישימני נגיד לעמו ומושל בבני |

11 |

|

vacat בריתו |

12 |

|

תחלת גב[ו]רה ה[דו]יד משמשחו נביא אלוהים אזי רא֯[י]תי פלשתי |

13 |

|

מחרף ממ[ערכות האיוב] אנוכי [ ] את |

14 |

|

|

Here is an English translation:

| 11Q5 Ps 151A & B | |

| 1 | of the Lord, who stand in the house of the Lord by night. Lift your hands in the holy place and bless |

| 2 | the name of the Lord May the Lord, maker of heaven and earth, bless you from Zion. |

| blank space | |

| 3 | A Hallelujah of David son of Jesse. Smaller was I than my brothers And the youngest of the sons of my father |

| 4 | And he made me shepherd of his flock And ruler over his kids My hands made a (musical) instrument And my fingers a lyre |

| 5 | And I rendered glory to the Lord I said within myself The mountains do not witness |

| 6 | to him, Nor do the hills declare; The trees have cherished my words And the flock my works. |

| 7 | For who can declare and who can speak, And who can recount the works of the Lord? Everything has God seen, |

| 8 | Everything he has heard, and he has heeded. He sent his prophet to annoint me, Samuel, |

| 9 | to make me great My brothers went out to meet him, Handsome of figure and handsome of appearance They were tall of stature |

| 10 | Handsome by their hair, The Lord God did not choose them. And he sent and took me |

| 11 | from behind the flock And annointed me with holy oil, And made me leader to his people And ruler over the sons of |

| 12 | his covenant |

| 13 | At the beginning of [Dav]id’s p[ow]er after the prophet of God had annointed him Then I s[a]w a Philistine |

| 14 | Uttering defiances from the r[anks of the enemy]. I […] ’t […] |

As you can see, the actual scroll does not divide the Hebrew psalm into poetic lines, but takes up the width of the column with as much text as possible. (By the way, the top of the column [lines 1 and 2] consists of all but the first part of Psalm 134 [LXX Ps 133]).

Comparing Sanders’s line divisions with that of the actual scroll raises an issue common with any analysis of the Dead Sea Scrolls; the issue of editorial reconstruction. A number of aspects of Sanders’s reconstruction of Psalms 151A and B have been severely criticized by scholars — especially his reconstruction of lines 6-8. That being said, even a quick comparison of LXX Psalm 151 with this text from Qumran suggests some sort of literary relationship between the texts, though as I noted above, the precise nature of that relationship is debated.