[I will be republishing my series on the Hebrew text of Jonah for my current introductory Hebrew class since I had to go back and fix the Hebrew in the posts]

The first chapter of the book of Jonah begins with Jonah’s call to go to Nineveh. But instead of heading for Nineveh, he heads the opposite direction to Tarshish aboard a ship filled with pagan sailors. Jonah’s presence on the ship does not bode well for the sailors, who eventually figure out Jonah is the reason their ship is in danger. After much prayer, they toss Jonah into the sea, after which he is swallowed by a divinely appointed “big fish.” Thus begins Jonah’s “Big Fish” story.

Jonah and the Sailors (1:1-16)

Hebrew Text

Hebrew Text

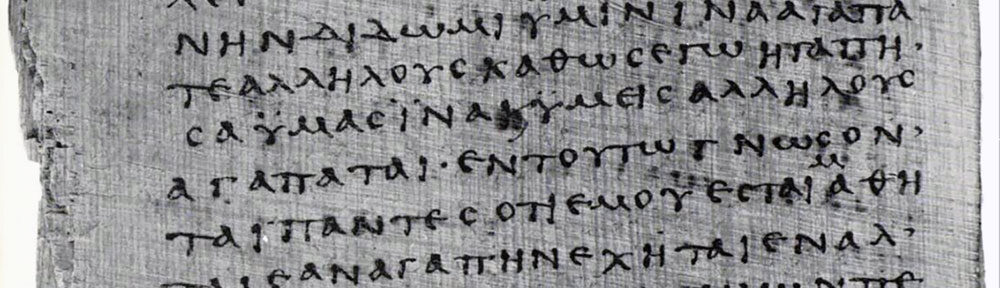

The Hebrew Text is taken from BHS. Click on the image to the right to view the passage in the actual Leningrad Codex (MS B19 A). To hear the chapter read in Hebrew, an MP3 file is available here.

וַיְהִי דְּבַר־יְהוָה אֶל־יוֹנָה בֶן־אֲמִתַּי לֵאמֹר׃ קוּם לֵךְ אֶל־נִינְוֵה הָעִיר הַגְּדוֹלָה וּקְרָא עָלֶיהָ כִּי־עָלְתָה רָעָתָם לְפָנָי׃ וַיָּקָם יוֹנָה לִבְרֹחַ תַּרְשִׁישָׁה מִלִּפְנֵי יְהוָה וַיֵּרֶד יָפוֹ וַיִּמְצָא אָנִיָּה בָּאָה תַרְשִׁישׁ וַיִּתֵּן שְׂכָרָהּ וַיֵּרֶד בָּהּ לָבוֹא עִמָּהֶם תַּרְשִׁישָׁה מִלִּפְנֵי יְהוָה׃ וַיהוָה הֵטִיל רוּחַ־גְּדוֹלָה אֶל־הַיָּם וַיְהִי סַעַר־גָּדוֹל בַּיָּם וְהָאֳנִיָּה חִשְּׁבָה לְהִשָּׁבֵר׃ וַיִּירְאוּ הַמַּלָּחִים וַיִּזְעֲקוּ אִישׁ אֶל־אֱלֹהָיו וַיָּטִלוּ אֶת־הַכֵּלִים אֲשֶׁר בָּאֳנִיָּה אֶל־הַיָּם לְהָקֵל מֵעֲלֵיהֶם וְיוֹנָה יָרַד אֶל־יַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה וַיִּשְׁכַּב וַיֵּרָדַם׃ וַיִּקְרַב אֵלָיו רַב הַחֹבֵל וַיֹּאמֶר לוֹ מַה־לְּךָ נִרְדָּם קוּם קְרָא אֶל־אֱלֹהֶיךָ אוּלַי יִתְעַשֵּׁת הָאֱלֹהִים לָנוּ וְלֹא נֹאבֵד׃ וַיֹּאמְרוּ אִישׁ אֶל־רֵעֵהוּ לְכוּ וְנַפִּילָה גוֹרָלוֹת וְנֵדְעָה בְּשֶׁלְּמִי הָרָעָה הַזֹּאת לָנוּ וַיַּפִּלוּ גּוֹרָלוֹת וַיִּפֹּל הַגּוֹרָל עַל־יוֹנָה׃ וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֵלָיו הַגִּידָה־נָּא לָנוּ בַּאֲשֶׁר לְמִי־הָרָעָה הַזֹּאת לָנוּ מַה־מְּלַאכְתְּךָ וּמֵאַיִן תָּבוֹא מָה אַרְצֶךָ וְאֵי־מִזֶּה עַם אָתָּה׃ וַיֹּאמֶר אֲלֵיהֶם עִבְרִי אָנֹכִי וְאֶת־יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵי הַשָּׁמַיִם אֲנִי יָרֵא אֲשֶׁר־עָשָׂה אֶת־הַיָּם וְאֶת־הַיַּבָּשָׁה׃ וַיִּירְאוּ הָאֲנָשִׁים יִרְאָה גְדוֹלָה וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֵלָיו מַה־זֹּאת עָשִׂיתָ כִּי־יָדְעוּ הָאֲנָשִׁים כִּי־מִלִּפְנֵי יְהוָה הוּא בֹרֵחַ כִּי הִגִּיד לָהֶם׃ וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֵלָיו מַה־נַּעֲשֶׂה לָּךְ וְיִשְׁתֹּק הַיָּם מֵעָלֵינוּ כִּי הַיָּם הוֹלֵךְ וְסֹעֵר׃ וַיֹּאמֶר אֲלֵיהֶם שָׂאוּנִי וַהֲטִילֻנִי אֶל־הַיָּם וְיִשְׁתֹּק הַיָּם מֵעֲלֵיכֶם כִּי יוֹדֵעַ אָנִי כִּי בְשֶׁלִּי הַסַּעַר הַגָּדוֹל הַזֶּה עֲלֵיכֶם׃ וַיַּחְתְּרוּ הָאֲנָשִׁים לְהָשִׁיב אֶל־הַיַּבָּשָׁה וְלֹא יָכֹלוּ כִּי הַיָּם הוֹלֵךְ וְסֹעֵר עֲלֵיהֶם׃ וַיִּקְרְאוּ אֶל־יְהוָה וַיֹּאמְרוּ אָנָּה יְהוָה אַל־נָא נֹאבְדָה בְּנֶפֶשׁ הָאִישׁ הַזֶּה וְאַל־תִּתֵּן עָלֵינוּ דָּם נָקִיא כִּי־אַתָּה יְהוָה כַּאֲשֶׁר חָפַצְתָּ עָשִׂיתָ׃ וַיִּשְׂאוּ אֶת־יוֹנָה וַיְטִלֻהוּ אֶל־הַיָּם וַיַּעֲמֹד הַיָּם מִזַּעְפּוֹ׃ וַיִּירְאוּ הָאֲנָשִׁים יִרְאָה גְדוֹלָה אֶת־יְהוָה וַיִּזְבְּחוּ־זֶבַח לַיהוָה וַיִּדְּרוּ נְדָרִים׃

Translation

Please note that my translation is more formal in nature and purposefully highlights literary and poetic features of the text. The versification follows the Hebrew text.

1:1 The word of YHWH came to Jonah son of Amittai, saying: 2 Get up, go at once to Nineveh, that great city, and proclaim against it; for their wickedness has come before me. 3 Jonah, however, got up to flee to Tarshish away from the presence of YHWH. So he went down to Joppa and found a ship going to Tarshish, and he paid its hire, and went down into it to go with them to Tarshish, from the presence of YHWH. 4 But YHWH hurled a great wind to the sea, and there was a great storm upon the sea that the ship thought about breaking up!

5 And the sailors were afraid and cried out, each to his own god; and they hurled the cargo that was in the ship into the sea to lighten [it] for them. But Jonah had gone down into the hold of the vessel and had lain down, and was in a deep sleep. 6 The captain went over to him and cried out, “Why are you sleeping so soundly? Get up, call upon your god! Perhaps the god will bear us in mind and we will not perish.” 7 The men said to one another, “Let us cast lots and find out on whose account this misfortune has come upon us.” They cast lots and the lot fell on Jonah. 8 They said to him, “Please declare to us — you who have brought this evil upon us — what is your business? Where have you come from? What is your country, and from what people are you?” 9 And he said to them, “I am a Hebrew and I fear YHWH, the God of heaven, who made the sea and the dry land.” 10 The men were greatly terrified [feared a great fear], and they said to him, “How could you have done this?” For the men knew that he was fleeing from the presence of YHWH, for so he had told them. 11 And they said to him, “What must we do to you so that the sea calms down for us?” For the sea was growing more and more stormy. 12 He answered, “Heave me overboard, and then the sea will calm down for you; for I know that this great storm came upon you on my account.” 13 Nevertheless, the men rowed hard to return to the dry land, but they could not, for the sea was growing more and more stormy against them. 14 Then they called to YHWH: “Oh, please, YHWH, do not let us perish on account of this man’s life and do not put innocent blood upon us! For You, O YHWH, have done just as you pleased.” 15 And they cast Jonah into the sea, and the sea stopped from its raging. 16 The men feared YHWH with a great fear, and they sacrificed a sacrifice to YHWH, and they vowed vows.

Translation & Text Critical Notes

For basic identification and parsing, please see the excerpts from Owens (PDF) or Beall and Banks (PDF). For bibliography noted in my post on “Resources for the Study of the Book of Jonah,” only short references will be provided here. See my “Mastering Biblical Hebrew” pages for more information on any Hebrew grammars and lexicons mentioned.

Verse 1

- וַיְהִי– This Qal prefix vav conversive apocopated form is at home in Hebrew narrative and is the typical opening for “historical” books like Joshua, Judges, 1Samuel, and Ruth (see AC 3.5.1 c).

- יוֹנָה בֶן־אֲמִתַּי – This “Jonah son of Amittai” is considered to be the nationalistic prophet of the same name mentioned in 2Kings 14:23-29.

Verse 2

- קוּם לֵךְ– Of the two imperative verbs, קוּם functions as an auxiliary verb to the principal verb לֵךְ and may be translated something like “Arise, go…” or better, “Go at once…” (GKC 120g).

- וּקְרָא עָלֶיהָ– The collocation of על with the verbקראtypically has negative connotations, hence my translation “proclaim against.” The parallel statement in Jonah 3:2 on the other hand has אל. While this change may only suggest the interchangeable nature of the prepositions (WO’C), the change to the more innocuous “proclaim to” in 3:2 may foreshadow the Ninevites’ positive response to Jonah’s message (see Ben Zvi).

- הָעִיר הַגְּדוֹלָה– The definite articles are functioning as weak demonstratives, “that great city” (AC 2.6.6). Alternatively, both adjectives could be modifying the noun, “Nineveh the great city” (J-M 138b; 141c; BHRG 30.2.2vii).

- כִּי־עָלְתָה רָעָתָם לְפָנָי– This phrase should be taken as causal (“because…”), providing the rationale for God sending the prophet to Nineveh (contra Sasson who understands it as asseverative). See AC 4.3.4a, i.

Verse 3

- מִלִּפְנֵי– This compound preposition is best translated as “away from the presence of” or even just “away from” (HALOT).

- תַרְשִׁישׁ– The identification of “Tarshish” is the subject of much spilled ink (see Sasson for a discussion). I tend to think of it as an ancient “Timbuktu.” Either way, the point is that Jonah headed in the exact opposite direction of Nineveh. Note that it occurs both with and without the directive ה in this passage

- אָנִיָּה– The footnote in BHS (sic L, mlt MSS Edd אֳניה cf 4.5) suggests that the pointing of אָנִיָּה is incorrect; it should be אֳניהas many other Masoretic texts indicate as well as the pointing in vv. 4 and 5.

- וַיִּתֵּן שְׂכָרָהּ– The antecedent of the 3fs possessive pronoun is clearly אָנִיָּה(“paid its [i.e., the ship’s] fare”). A number of Jewish traditions (and modern authors) suggest this indicates Jonah rented the entire ship (and thus was wealthy), which again emphasizes the extent to which he was willing to avoid God’s call.

- עִמָּהֶם– While the sailors are not mentioned until v. 5, the 3mp object suffix on עִמָּהֶם refers to the sailors included in the sense of the term אָנִיָּה (GKC 135p).

Verse 4

- וַיהוָה– The fronted subject with the conjunction breaks the series of vav conversives and introduces a different subject and is best rendered as “but YHWH…” (AC 3.5.4; 5.1.2b.2).

- חִשְּׁבָה לְהִשָּׁבֵר– Many translations render this combination of Piel affix 3fs and Nifal infinitive construct something like, “the ship was about to break up” (NASB) or the like. I prefer to take it as an example of personification or prosopopoeia where the ship is portrayed as thinking about breaking up. This understanding is supported by the fact thatחשׁבis always used elsewhere with an animate subject. See WO’C 23.2.1 for the sense of the Nifal here.

Verse 5

- אִישׁ אֶל־אֱלֹהָיו– This is a distributive use ofאִישׁ, “each to his own god” (GKC 139b). It could also be translated “each to his own gods” since the sailors were evidently pagan.

- לְהָקֵל– The Hifil infinitive construct needs an object, i.e., “to lighten [it].”

- “But Jonah had gone down… and had lain down, and had fallen fast asleep.” The fronted subject once again interrupts the sequence of wayyiqtol verbs and marks a new subject which contrasts Jonah’s actions with those of the sailors.

- וַיֵּרָדַם– The verbרדםmeans “deep sleep” and is from the same root as the noun used to describe Adam’s sleep when the woman was taken out of his side in Gen 2:21. The Septuagint translatesרדםwith the verb ῥέγχω “snore,” which adds some humour to the scene as Jonah’s snoring was apparently loud enough for the captain of the ship to hear him from above deck as he comes down to Jonah and asks him what is he doing snoring when a life threatening storm has been thrown to the sea by YHWH (see my post on snoring here)!

Verse 6

- רַב הַחֹבֵל– Lit., “chief of the sailors,” i.e., captain.

- מַה־לְּךָ נִרְדָּם– The Nifal participle may be functioning as a subordinate accusative of state, i.e., the object of the non verbal interrogative construction, lit. “what [is it] to you, sleeping?” = “why are you sleeping so soundly?” (see GKC 120b; J-M 127a, 161i). I am almost tempted to take the participle as a vocative and translate it something like, “What is the matter with you, sleepy head?!”

- יִתְעַשֵּׁת – The Hitpael of עשׁתis a hapax that means something like “bear in mind” (HALOT).

Verse 7

- Note the cohortative הs on וְנַפִּילָהand וְנֵדְעָה .

- בְּשֶׁלְּמִי– The compound particle is made up of the preposition ב + relative שׁ + preposition ל + interrogative מי; together it means “on whose account” (HALOT), or “for whose cause” (GKC 150k). For the combination of the relative שׁ and preposition ל, see WO’C 19.4a n15.

- Note the idiom of “casting lots” with the verb נפל.

Verse 8

- There is a rather oblique text critical footnote in BHS (“nonn add Hab” = “several manuscripts have added”) marking off the phrase בַּאֲשֶׁר לְמִי־הָרָעָה הַזֹּאת לָנוּ, “on whose account has this evil come upon us” (as well as a similar phrase in v. 10; see below). The footnote suggests the editors of BHS considered this phrase to be an addition or later gloss. While they do not provide any reasons, it is likely based on two things: (1) the phrase is omitted in the LXX and a number of Masoretic manuscripts and (2) it appears to be a doublet or repetition of virtually the same phrase in v. 7. While this is certainly possible, the phrase is found in the huge majority of Masoretic texts as well as scrolls from Qumran. Furthermore, the absence of the phrase in some Hebrew and Greek manuscripts can easily be explained by homoeoteleuton (skipping over words between words with similar endings) triggered by the repetition of לָנוּ in the Hebrew or ἐν ἡμῖν in the Greek. That being said, the question of how to translate it remains. The most straightforward translation is to repeat the question, “on whose account has this evil come upon us?” even though they already know the answer and Jonah doesn’t answer it (see NASB, KJV, NIV). Another, perhaps better, option is to render it as a relative clause, “you who have brought this evil upon us” (see JPS and Sasson). This recognizes the subtle difference of the construction בַּאֲשֶׁר לְמִי־הָרָעָה הַזֹּאת לָנוּ with בְּשֶׁלְּמִי הָרָעָה הַזֹּאת לָנוּin the preceding verse.

- The sailors pose four questions to Jonah: (1) what is your mission? (2) from where are you coming? (3) what is your (home)land? and (4) from what people are you? (the combination of the interrogative with מן does not produce any notable change in meaning; J-M 143g).

Verse 9

- עִבְרִי אָנֹכִי– The order of predicate –> subject in the verbless clause indicates classification and refers to a general class (Hebrews) of which the subject is a member (WO’C 8.4.2). The term “Hebrew” is typically only used in the HB to imply a contrast with foreigners (GKC 2b).

- The irony of Jonah’s confession is marvelous; while his confesses he fears “YHWH, the God of heaven, who made the sea and the dry land,” he also appears to believe he can flee from this same YHWH by taking a sea voyage!

Verse 10

- וַיִּירְאוּ הָאֲנָשִׁים יִרְאָה גְדוֹלָה– This construction of a verb with a direct object derived from the same root is called an “internal accusative” or “cognate accusative.” It serves to strengthen the verbal idea and may be translated “the men were greatly terrified” or the like (AC 2.3.1c; GKC 117q).

- מַה־זֹּאת– The linking of the interrogative pronoun to the feminine demonstrative is an exclamation of shock or horror rather than a query (Sasson).

- כִּי הִגִּיד לָהֶם– This phrase is marked off as a gloss in BHS (see discussion on v. 8 above).

Verse 11

- מַה־נַּעֲשֶׂה לָּךְ– The prefix form in this context likely has a modal nuance, i.e., “what must we do to you…” (J-M 113m).

- וְיִשְׁתֹּק– The prefix + vav form indicates purpose, “so that” (J-M 169i; BHRG 21.5.1.iv).

- הוֹלֵךְ וְסֹעֵר– The participles form a hendiadys to convey repetition and increasing intensity, with הלךfulfilling an auxiliary role (GKC 113u).

Verse 12

- וְיִשְׁתֹּק– The prefix + vav form in Jonah’s reply has a consecutive sense, “then…” (J-M 169i).

Verse 13

- וַיַּחְתְּרוּ– The verb חתר means “to dig”; it is used here to suggest hard rowing or “digging” into the water with their oars.

Verse 14

- The first person plural cohortatives are found here with the particle of entreaty נָא, often translated as “please” or the like (J-M 114f; GKC 105, 108c).

- כִּי־אַתָּה יְהוָה כַּאֲשֶׁר חָפַצְתָּ עָשִׂיתָ– This clause is a bit difficult to unpack. Sasson takes it and the preceding clause as separate motivations offered by the sailors to God: “Indeed, you are YHWH; and whatever you desire, you accomplish.” While this is possible, I think Sasson is giving too much weight to the zaqef qaton on YHWH. I have translated YHWH as a vocative and the relative clause as modifying אַתָּה“you.”

Verse 15

- מִזַּעְפּוֹ– The Qal infinitive construct with the prepositionמן (and the 3ms suffix) serves as a verbal complement to עמד, “the sea stopped from its raging.”

Verse 16

- וַיִּירְאוּ הָאֲנָשִׁים יִרְאָה גְדוֹלָה אֶת־יְהוָה– The verb here has double accusatives: YHWH is the affected object (the object that existed apart and before the action of the verb, but is reached by the verb), while the “great fear” is the internal object (the object is an abstract noun of action typically of the same root as the verb, and thus a cognate accusative) (AC 2.3.1; J-M 125u n1).

- Note again the irony that the pagan sailors are more devout than Jonah.

Comments

While I will leave most of the larger questions of interpretation to a later post, I do want to highlight a few things from chapter one.

First, it is difficult if not impossible to pick up on a significant key word for the book of Jonah: גָּדוֹל“great” or “big.” Everything in Jonah is “great”: Nineveh (v. 2), the wind (v. 4), the storm (v. 4, 12), the sailors’ fear (v. 10) and their repentance (v. 16). In later chapters we will encounter a “great” or “big” fish (2:1), among other things.

Second, the frequent use of גָּדוֹלas well as some of the other language in this (the ship thinking) and later chapters (the animals putting sackcloth on themselves in 3:8), “shifts the story to the fabulous” as Sasson suggests. I will come back to this observation in a later post.

Finally, when examining the characterization of Jonah, YHWH, and the pagan sailors in this chapter it is striking:

- Jonah does exactly the opposite of what YHWH calls him to do: instead of getting up and going (קוּם לֵךְ), he got up to flee (וַיָּקָם יוֹנָה לִבְרֹחַ ), and then in contrast to getting up, he has a series of descents (ירד) in order to get away from YHWH’s call. And of course, as I already noted, the irony between Jonah’s flight and his confession is stunning.

- The sailors come across much better than Jonah. Their actions are often parallel to those of YHWH: they, like YHWH, tell Jonah to “get up” and “call” (1:2, 6); they both “cast to the sea” (1:4, 5, 15). In addition, a contrast is set up between the sailors and Jonah: Jonah’s fear (1:9) vs. the sailors’ fear (1:10); and “perish” in the mouths of the sailors (1:7, 14) vs. from Jonah’s perspective (4:10).

Well, this post has ended up longer than I anticipated. I better end it here. We’ll pick up Jonah chapter three next.