[One of my main areas of research is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint. This post talks about how the Greek text can be used to help us understand the Hebrew original. It was originally published 08/2009]

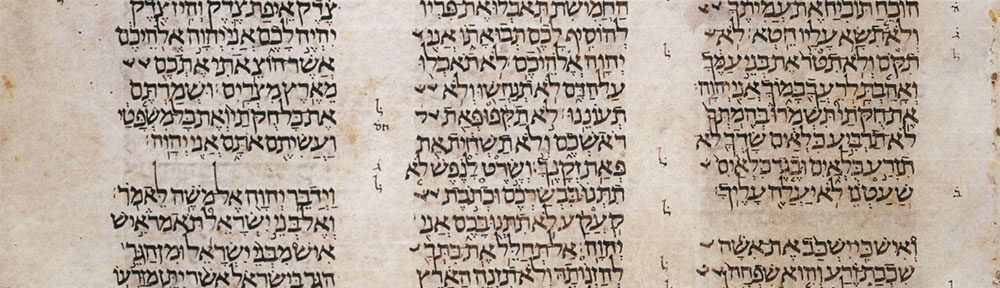

In this post I am laying a foundation for my next installment in my series on Psalm 151 in the Biblical Tradition, by discussing how to retrovert a text from one language into another. This is most commonly done when using the Septuagint in the textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. Thus, in order to employ the LXX in textual criticism one must retrovert the Greek text back into Hebrew (for more information on the Septuagint and textual criticism in general see my series of posts on Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible). In many cases retroverting a text is easier said than done.

Here are some tips for retroverting a text:

Focus on the translation technique of the individual book in question. The LXX is not a uniform translation. Various translators at different times, with varying philosophies of translation and different language capability, translated different portions of the Hebrew Bible to make up the LXX. For example, the translation of the Torah is a good formal translation, the translation of the Psalter is very formal, while the translations of Proverbs and Isaiah are less so. Thus one cannot assume that the way one translator rendered a particular Hebrew word or construction will be the same fora translator of a different book. Each individual book of the LXX has its own idiosyncrasies to its translation; thus a careful examination of its translation technique is necessary before one can retrovert the text with any confidence.

Examine the different ways a translator renders a particular word. In order to figure out what Hebrew word may be behind a particular Greek word in a passage, you need to look up every instance of the Greek word in question within the biblical book and note what Hebrew word was being rendered. There are a number of useful resources that will help you with this task. If you have a Bible software package with the original language modules, then you can do a Greek lemma search and see what Hebrew was being translated. Even more ideal is if you have Emauel Tov’s The Parallel Aligned Hebrew-Aramaic and Greek Texts of Jewish Scripture module where you can see the equivalent elements of the MT and the LXX (as reconstructed by the editor). For more on the different software programs available for Biblical Studies, see my Bible Software pages. If you do not have a Bible software package, then you can manually look up how a word is with Takamitsu Muraoka’s Hebrew/Aramaic Index to the Septuagint: Keyed to the Hatch-Redpath Concordance (Baker Academic, 1998; Buy from Amazon.ca | Amazon.com) which also comes included in Edwin Hatch, Henry A. Redpath, A Concordance to the Septuagint: And the other Greek Versions of the Old Testament – Including the Apocryphal Books (Second edition, two volumes in one; Includes Muraoka, “Hebrew/Aramaic Index”; Baker Academic, 1998; Buy from Amazon.ca | Amazon.com).

Identify a pattern. If a clear pattern emerges, propose a retroversion. When you examine the different ways an individual book tends to translate a word into Greek, and if there is a clear default rendering, then you can be fairly confident in proposing the retroversion. While you can never be 100% certain with any retroversion, some will be more certain than others. If a clear pattern doesn’t emerge, or if the words in question do not occur frequently enough in the book under study, then you will need to broaden your investigation to see how the word is rendered elsewhere in the LXX. While this will not produce as clear of results as the previous situation, you can still produce a workable retroversion.

With these principles in mind, the Septuagint may be employed quite fruitfully in the textual criticism of the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible. Of course, retroversion may also be used with texts of other languages, and even in ascertaining the relationship between Hebrew Dead Sea Scroll texts and the Septuagint (as I will seek to do in my next post on Psalm 151).