Stephen Goranson brought my attention (via the Biblical Studies email list) to the following story by Henk Schutten: “Dead Sea Scrolls in the Trade.” The story was published in Dutch newspaper het Parool (An English Translation is available here). The article discusses four Dead Sea Scroll fragments which were offered for sale by a dealer at the 2003 Maastricht Art Fair, Tefaf. These scrolls were linked to the Kando family. What I found surprising is the linking of these scrolls that were sold on the black market and the recent recovery of the fragments of a Leviticus Scroll (see a list of my blog entries on this subject here). Here is the relevant excerpt:

In March last year, it was revealed that the Kando family had further new fragments from the book of Henoch, a Qumran-manuscript about Judgement Day. The husband and wife team, Esther and Hanan Eshel, announced the discovery of the Henoch fragments last year, as well as last month a further revelation. They had managed to get hold of two Hebrew fragments from the Book of Leviticus, which had just been discovered by Bedouins in a cave in Nahal Arougot, in the desert of Judea. The story goes that Hanan Eshel, as an ancient historian at the University of Bar Ilan, had been approached to assess the authenticity of the parchments, but instead bought them for $3,000, because he was afraid that the find – so he says – would be smuggled out of the country.So many discoveries in so short a period, in an area that has been so exhaustively explored by archaeologists – it cannot be a coincidence – that it is the word among the researchers in the field. The American philologist Edward Cook, a renowned international translator of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and author of ‘Solving the mysteries of the Dead Sea Scrolls’, states that the involvement of the Kando family is a virtual certainty in the new finds. He adds, “More than likely that the Kando family have had the scrolls or fragments for a long time”. “It is known that in the 50s many Bedouins first offered their finds to Kando. There is no guarantee whatsoever that Kando did not keep part of the material for himself. Everything indicates that the family are trying to market the fragments” (Emphasis added).

I guess my question is whether there is any evidence whatsoever that links the Leviticus fragments to the Kando family? From my interview with Hanan Eshel (20 July 2005), it seems unlikely that the Leviticus scroll fragments have anything to do with the Kando family.

The Discovery and Provenance of the Leviticus Fragments

Here is the story of how the Leviticus fragments were discovered and came into the possession of Hanan Eshel based on my interview with him.

The story begins in 2000 when Hanan Eshel was teaching a seminar on the Bar Kokhba revolt. In one of his lectures he was talking about the refuge caves — the places Jews had fled in 135 CE when the Roman army captured Judea and Jews were trying to find shelter — and he pointed out that there were 27 known refuge caves. In the middle of the lecture he noted that it was odd that numerous caves were discovered in the area that was in Israeli hands, but in the area that was in Jordanian hands there was only one place in Waddi Murrrabat identified.

Some of the students in this class decided to survey the area that used to be in Jordanian hands. The survey started in 2001. A total of 350 caves were surveyed with metal detectors. From this five caves were discovered that were used for refuge. Early on in this survey, the survey team’s jeep was broken into and all the equipment was stolen. At that point they decided to hire some Bedouins to look after the vehicle when they were going down the cliffs.

Then later, one day in 2004, one of the Bedouins who had been hired on occasion to look after the vehicle called and said that some Bedouins had found fragments of a scroll and that he wanted to show them to Eshel in order to get an estimation of their worth.

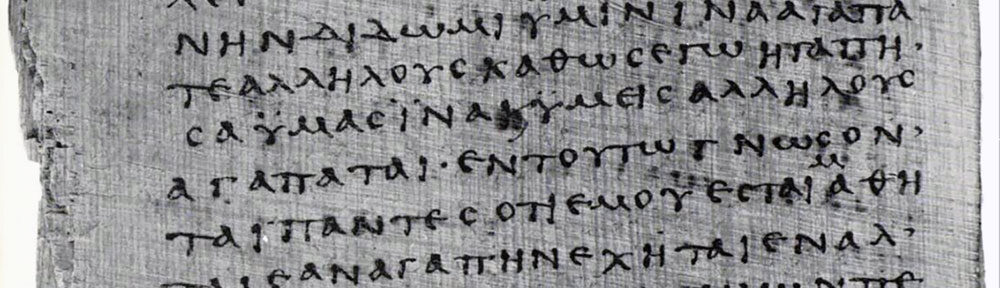

The rest of the story is well-known by now. Hanan Eshel examined the fragments at an abandoned Jordanian police station the night of 23 August 2004 (here is a picture taken that evening), but then had to leave to teach in the United States. While the Bedouin said he had been offered $20,000 for the scroll on the black market, that sale never materialized. When Hanan got back to Israel and discovered that the fragments were still around and that they were being further damaged by the Bedouin, only then did he purchase them for $3000 USD on behalf Bar Ilan University and turn them over to the Antiquities Authority.

What may not be well-known is that after securing the Leviticus fragments, Hanan was taken to the cave where the fragments were purportedly found. From a controlled examination of the cave, Hanan found evidence that the cave had been looted by Bedouin in August of 2004 (e.g., metal poles that they walked into the cave on were still in the walls [I believe], newspapers dated to August 2004 were found in the cave, etc.). He also found pottery and textiles consistent with others from the Bar Kokhba period in the cave. Interestingly, right from the very beginning the Bedouin described the fragments as being from the Bar Kokhba period. This was because, as Eshel later discovered, the Bedouin had found Bar Kokhba coins in the cave where the scroll was found. While Eshel did not find the fragments in situ, I think that it is pretty clear that the proper cave was identified.

Perhaps this whole story is a ruse by the Bedouin to sell fragments of a scroll from the Kando family’s hidden stash of scrolls (which may very likely exist). Perhaps they climbed the cliffs in the Judaean desert to create a fake cave to show Eshel. I personally think that is all highly doubtful.

Hopefully now that more of the story of the Leviticus scroll’s origin is known, it will dispel some of the speculation.

I had the absolute privilege of interviewing Professor Hanan Eshel earlier today for an article I am writing for a Canadian national newspaper (

I had the absolute privilege of interviewing Professor Hanan Eshel earlier today for an article I am writing for a Canadian national newspaper (