The Leviticus scroll discovered (or should I say recovered) by Israeli Archaeologist Hanan Eshel is back in the news. According to an article in Ha’aretz, Eshel is claiming that the Israeli Antiquities Authority is performing unnecessarily obtrusive tests on the fragments in order to determine their authenticity.

Here is the news item, “Archaeologist: Antiquities Authority destroying Leviticus scroll,” by Yair Sheleg:

Professor Hanan Eshel, the archaeologist who two years ago uncovered scroll fragments of the Book of Leviticus, says the Israel Antiquities Authority, which now has the finds, has cut out large chunks of the scroll on the pretext that its dating needed to be examined.

This was not a necessary procedure, says Eshel, since “experts say it was possible to test the dating without an intrusive examination and in the worst case scenario by cutting a tiny, peripheral portion of the scroll.”

Relying on internal sources in the Antiquities Authority, Eshel says “there had even been plans to cut letters from the scroll but the employees that were asked to do so refused.”

Eshel ties the behavior of the Authority to a dispute that emerged between him and officials there and “their desire to prove that the scroll is a forgery.”

Amir Ganor, director of the unit for the prevention of theft in the Antiquities Authority, said in response that “in order to carry out the examination we could not avoid making certain cuts in the scroll itself. This is acceptable in every examination of this sort. We cut only two small parts, one-half centimeter each, from the end of the scroll. At no stage was there any thought of cutting letters, only to scrape off some ink in order to examine it. The minute it became clear to us that we could not have unequivocal results from such an examination, we did not do it.”

However, the photographs published here [where? there was no link or no pictures!] suggest the scroll cuts are significantly more extensive than what Ganor acknowledges and encompass nearly all the part of the scroll that has no writing on it.

Ganor said examinations of the scroll have undermined Eshel’s claim that the finding is authentic.

“I can not give any details because the topic is part of an ongoing investigation of this matter, but the examinations show that different portions of the scroll were written in different periods, which is a blow to the claim that the scroll is homogeneous.”

Eshel, on the other hand, is eager to offer more information on the subject. He says: “The information that I have is that the examination that was carried out at the Weizmann Institute did indeed show that the two portions that were sent for examination belong to different periods – one about 2,000 years ago, and the other about 1,200 years ago. On the other hand, another examination carried out at Oxford [University] attributed both to a period 2,000 years ago.”

Eshel says the Weizmann test results were flawed because of “the use of cleaning and preservation materials. I am not an expert on such exams, but the experts told me that such treatment may certainly result in a flawed examination. In any case, the writing on both segments clearly belongs to the Second Temple period and definitely does not conform to the Mameluk period, which is what the Weizmann Institute examination points to. Moreover, during the search in the cave where we found the scroll, we uncovered other archaeological finds for the period of the Bar-Kokhba revolt, proving the dating.”

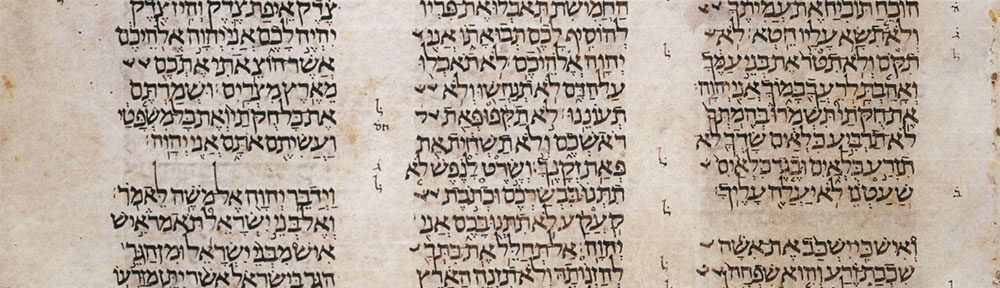

I had covered the discovery of the Leviticus scrolls quite extensively a couple years back, so I have an interest in this story. You can see all of my previous posts here, including a step-by-step reconstructions of the fragments. Here is a picture of the fragments shortly after they were recovered:

I would think that if tests could be done on the manuscript without destroying large parts of it, then the IAA would do so.

I wish the news article contained the image that showed how much of the manuscript was cut.

(HT Dr. Claude Mariottini)

A couple new books on the Dead Sea Scrolls came to my attention recently and appear to be quite interesting.

A couple new books on the Dead Sea Scrolls came to my attention recently and appear to be quite interesting.