[This post was originally published 08/2009]

Chris Heard over at Higgaion posted an interesting discussion of Kurt Noll’s article, “The Ethics of Being a Theologian,” over at the Chronicle of Higher Education web site. While I agree with Chris that Kurt’s article is full of unsubstantiated “truth claims,” I still recognize the distinction between religious studies and theology. While my sympathies with Noll could be because he is a fellow Canadian and my perception is that Canadians draw the distinction between religious studies and theology more sharply than those in the USA, the fact is that I try to live in both worlds and tend to eschew the combative and dualistic nature of the “Religious Studies vs. Theology” debate.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone to learn that the distinction between religious Studies and theology is a matter of some debate. Since the end of the nineteenth century, the discipline of Religious Studies has typically been understood to be the value-neutral and objective study of religions, while Theology is the confessional or particularistic study of one religion (See Donald Wiebe, “The Politics of Religious Studies,” CSSR Bulletin 27 [November 1998]: 95-98, where he argues forcefully for this distinction. Wiebe has long been a Canadian proponent for the continuing role of the academic study of religion within the context of a public university, by which he means the value-free study of religion free from any religious or confessional goals).

The distinction between Religious Studies and Theology played an important part in the establishment of Religious Studies departments in a number of universities in Europe and North America – though significantly not all educational institutions thought that the distinction was necessary. While this distinction is certainly characteristic of Canadian public universities, there are a number of institutions in Europe and North America that have combined departments of Religion and Theology (and that is what we attempted to do at the now defunct Taylor University College).

This traditional demarcation has also been challenged on some fronts in light of the postmodern recognition that there is no real objective, value-neutral study of religion (or any other subject for that matter). While I wholeheartedly agree with this recognition, that does not mean there is no distinction between religious studies and theology — it just means that any claims to be “objective”or “neutral” should be dismissed. We all engage our disciplines from our horizon with all of our own prejudices and presuppositions. What it means, however, is that the differences between the disciplines are only the rules agreed upon by those working within them. And each discipline works out different rules of engagement. (For an interesting discussion of postmodern theories of religious studies, see the interaction between Garrett Green, “Challenging the Religious Studies Canon: Karl Barth’s Theory of Religion,” Journal of Religion 75 [1995]: 473-86; Russell T. McCutcheon, “My Theory of the Brontosaurus”: Postmodernism and ‘Theory’ of Religion,” Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 26 [1997]: 3-23, and William E. Arnal, “What if I Don’t Want to Play Tennis?: A Rejoinder to Russell McCutcheon on Postmodernism and Theory of Religion,” Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 27 [1998]: 61-68; see also McCutcheon’s response, “Returning the Volley to William E. Arnal” on pp. 67-68 of the same issue). In practice, Religious Studies in the Canadian public university context tends to be the study of religion which does not privilege one religious discourse above another (notice I didn’t say “scientific” study of religion, since I find those that throw around the term “scientific” do so with prejudice against anything not deemed “scientific”). Theology, on the other hand, is typically defined as the study of one religion from a confessional standpoint. Thus the insider/outsider demarcation remains.

It is also possible to make a distinction between the academic disciplines of theology and biblical studies. On one level theology is a discipline distinct from biblical studies. Christian Theology, as one recent work defined it, is “an ongoing, second-order, contextual discipline that engages in critical and constructive reflection on the faith, life, and practices of the Christian community” (Stan Grenz and John Franke, Beyond Foundationalism. Shaping Theology in a Postmodern Context (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 2001) p. 16). As such, “Christian Theology” seems to me to be a normative insider job rather than purely descriptive discipline. Biblical studies, on the other hand, is an inclusive, multifaceted discipline that centers on the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament and Christian New Testament and that includes scholars from a variety of different religious and methodological perspectives. That being said, there are a large number of biblical scholars — indeed an entire a sub-discipline of biblical studies — who are also confessional and theological in their approach. That is, they are not only interested in describing the message of the Apostle Paul, they also want to engage the question of how Paul’s message may be relevant to the community of faith today.

In the light of the above distinctions, much of what I do would fall under the rubric of theology. I teach at a confessional institution from a confessional perspective, and one of my educational goals is to encourage students to critically reflect on their own religious tradition and integrate this faith with all aspects of their lives. That being said, I chaff at Kurt’s characterization that I “do not advance knowledge” but only “practice and defend religion.” My classes, while taught from a confessional perspective, are not the sort of indoctrination or apologetics that Kurt seems to think they must be. My teaching incorporates a broad methodological perspective that seeks to take account of a variety of critical and ideological approaches representative of the broader religious studies/biblical studies guild. Perhaps the difference is that I don’t stop there. I seek to interact with and explore how this broader perspective relates to the theological interpretation of scripture for the community of faith. So I am not sure that the relationship between “religious studies” and “theology” is an “either/or” relationship. I prefer to view it as a “both/and” relationship where the theological task is seen as “going beyond” the methods and questions of religious studies to include the personal faith integrative task as well. For what it’s worth, lately I find that I am far more interested in the latter issues than the former.

Either way, no matter where you stand on the debate, Peter Donovan makes an excellent point when he notes that

the scientific study of religion can ill afford to insulate itself from the thinking of others interested in the same subject-matter, merely because they may hold very different views about theory and method (Peter Donovan, “Neutrality in Religious Studies,” in The Insider/Outsider Problem in the Study of Religion. A Reader [ed., Russell T. McCutcheon; New York: Cassell, 1999], p. 245).

I would add that the theological study of religion can ill afford to insulate itself from those who take a religious studies approach as well! What is perhaps most important for any approach to the study of religion is that the approach is academic and methodologically sound and rigorous. And I happen to think, contra Kurt Noll, that this is possible for both scholars of religious studies and theologians!

In the second sermon I painted a profile of what I believe are some important characteristics of an “intellectually mature believer.” First and foremost, I underscored the importance of “epistemic humility” based on our fallenness, fallibility and finitude. The second characteristic was openness. More particularly, I emphasized the importance of openness to God and Scripture, openness to all truth (no matter where it may be found), and a genuine openness to others. By openness I do not mean a wishy-washy relativism, but something called “critical commitment” where you know what you believe and why and hold it with faith, moral courage, and epistemic humility. My final characteristic of an intellectually mature believer was that he or she should have as a goal integration. Here I was arguing for a somewhat unified/integrated Christian perspective on the world and our faith (I consider the modifier “somewhat” very important). This “unified view” is often referred to as a “worldview” or “world and life view.” While there are a number of limitations to the concept of a worldview (especially the notion that there is such an animal as “the Christian worldview” or that worldviews are somehow impervious to culture rather than embedded in culture), I still find it a helpful concept for thinking about thinking.

In the second sermon I painted a profile of what I believe are some important characteristics of an “intellectually mature believer.” First and foremost, I underscored the importance of “epistemic humility” based on our fallenness, fallibility and finitude. The second characteristic was openness. More particularly, I emphasized the importance of openness to God and Scripture, openness to all truth (no matter where it may be found), and a genuine openness to others. By openness I do not mean a wishy-washy relativism, but something called “critical commitment” where you know what you believe and why and hold it with faith, moral courage, and epistemic humility. My final characteristic of an intellectually mature believer was that he or she should have as a goal integration. Here I was arguing for a somewhat unified/integrated Christian perspective on the world and our faith (I consider the modifier “somewhat” very important). This “unified view” is often referred to as a “worldview” or “world and life view.” While there are a number of limitations to the concept of a worldview (especially the notion that there is such an animal as “the Christian worldview” or that worldviews are somehow impervious to culture rather than embedded in culture), I still find it a helpful concept for thinking about thinking. Tomorrow evening I will be picking up Dr. Kenton Sparks at the airport. He is the speaker for Taylor University College’s “Faith & Culture Conference” which runs Thursday and Friday of this week. The title of this year’s conference is “God’s Word in Human Words: The Prospects and Perils of Believing Criticism.”

Tomorrow evening I will be picking up Dr. Kenton Sparks at the airport. He is the speaker for Taylor University College’s “Faith & Culture Conference” which runs Thursday and Friday of this week. The title of this year’s conference is “God’s Word in Human Words: The Prospects and Perils of Believing Criticism.” What Kent will be drawing our attention to the human side of Scripture. And he is well-equipped to do such a task. He holds the PhD from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, where he specialized in the study of the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East (his adviser was John Van Seters). His publications include numerous articles on the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, as well as four books:

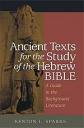

What Kent will be drawing our attention to the human side of Scripture. And he is well-equipped to do such a task. He holds the PhD from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, where he specialized in the study of the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East (his adviser was John Van Seters). His publications include numerous articles on the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, as well as four books: Kent’s Ancient Texts for the Study of the Hebrew Bible is one of the best and most recent guides to all of the background literature to the Old Testament. It includes an introduction to comparative study of ANE texts and ANE archives and libraries, as well as a discussion of all of the relevant texts organized by genre. Original publication data and other useful bibliography is included for each ancient text — I highly recommend it. At present, Kent is preparing a book-length treatment of Israelite origins for Oxford University Press.

Kent’s Ancient Texts for the Study of the Hebrew Bible is one of the best and most recent guides to all of the background literature to the Old Testament. It includes an introduction to comparative study of ANE texts and ANE archives and libraries, as well as a discussion of all of the relevant texts organized by genre. Original publication data and other useful bibliography is included for each ancient text — I highly recommend it. At present, Kent is preparing a book-length treatment of Israelite origins for Oxford University Press.