Ah, Valentine’s Day has arrived and love is in the air. And when I think of love I think of the sexiest book in the Hebrew Bible, the Song of Songs (perhaps better referred to as the Most Excellent of Songs, understanding שׁיר השׁירים as a superlative construction).

Despite the long and proud history of allegorical interpretations of the Song as depicting the love between Yahweh and Israel or Christ and the church, virtually all modern commentators maintain that the Song of Songs is a book of poetry celebrating human erotic love (a variety of sub-genres have also been suggested, such as a marriage song, drama, or even a sacred marriage text). This interpretation is supported by discoveries of similar love poetry in the ancient Near East, particularly Egypt.

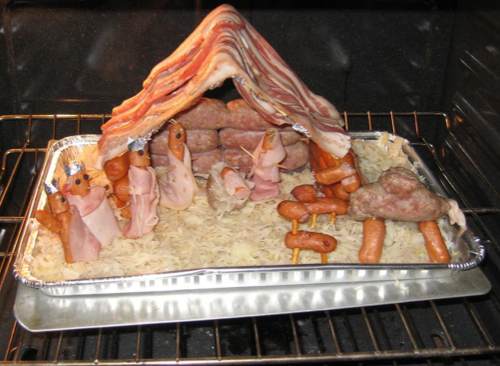

There are many challenges in translating the Song of Songs. There is an extraordinarily large number of hapax legomena (words that only occur once) in the Song as well as many other rare words and forms. But perhaps the most difficult challenge when translating the book is how to render the innumerable metaphors and smilies found within its verses (for a visual example of how not to understand the metaphorical language, see my post “Love Poetry for Biblical Literalists.”)

As I discussed in a previous post (“Dogs, Urine, and Bible Translations: On the Importance of Translating Connotative Meaning“), modern translations tend to be either “formal” (word for word) or “dynamic” (sense for sense). It is actually more accurate to say that modern translations will all fall somewhere on the continuum between the two translation options. The tension between the two translation methods can be especially noticed in the way translations render metaphors and smilies, since more dynamic translations will unpack the metaphors far more than formal translations.

Compare, for instance, the following two translations of Song of Songs 4:1-14, one from the New Revised Standard Translation (a formal translation) and the other from the New Living Translation (a more dynamic translation).

| NRSV | NLT |

| 1How beautiful you are, my love, how very beautiful! Your eyes are doves behind your veil. Your hair is like a flock of goats, moving down the slopes of Gilead. 2Your teeth are like a flock of shorn ewes that have come up from the washing, all of which bear twins, and not one among them is bereaved. 3Your lips are like a crimson thread, and your mouth is lovely. Your cheeks are like halves of a pomegranate behind your veil. 4Your neck is like the tower of David, built in courses; on it hang a thousand bucklers, all of them shields of warriors. 5Your two breasts are like two fawns, twins of a gazelle, that feed among the lilies. 6Until the day breathes and the shadows flee, I will hasten to the mountain of myrrh and the hill of frankincense. 7You are altogether beautiful, my love; there is no flaw in you. |

1How beautiful you are, my beloved, how beautiful! Your eyes behind your veil are like doves. Your hair falls in waves, like a flock of goats frisking down the slopes of Gilead. 2Your teeth are as white as sheep, newly shorn and washed. They are perfectly matched; not one is missing. 3Your lips are like a ribbon of scarlet. Oh, how beautiful your mouth! Your cheeks behind your veil are like pomegranate halves — lovely and delicious. 4Your neck is as stately as the tower of David, jeweled with the shields of a thousand heroes. 5Your breasts are like twin fawns of a gazelle, feeding among the lilies. 6Before the dawn comes and the shadows flee away, I will go to the mountain of myrrh and to the hill of frankincense. 7You are so beautiful, my beloved, so perfect in every part. |

Notice how the NLT tries to make the meaning of the metaphors more understandable. Thus, instead of her hair being simply compared to a flock of goats, the point of the comparison is elaborated: her hair “falls in waves, like a flock of goats frisking down the slopes of Gilead” (4:1). Similarly, the point of the comparison between her teeth and the flock of newly washed ewes is made explicit: her teeth “are as white as sheep, newly shorn and washed” (4:2). The same stands true for the comparison between her neck and the tower of David: “Your neck is as stately as the tower of David” (4:4).

The problem with a more dynamic translation is that many more interpretive questions have to be answered before translating. Consequently, dynamic translations are by their very nature much more interpretive than formal ones. Some of the comparisons are straightforward enough, such as her lips being like a “scarlet thread” or the ordered whiteness of her teeth being compared to the rows of newly washed and shorn sheep. It is more of a problem, however, when the nature of the comparison — whether metaphor or simile — is not entirely clear. Take, for example, the comparison between the lover’s hair and the flock of goats. The NLT understands the comparison as primarily concerned with its flowing movement. But what if the metaphor is complex? Perhaps the comparison has in view both her hair’s flowing movement as well as its black colour? The NLT recognizes this at times and renders a two dimensional comparison accurately, such as the comparison between the woman’s cheeks (or temples?) and pomegranate slices: “Your cheeks behind your veil are like pomegranate halves — lovely and delicious” (4:3).

The NLT, however, is not consistent in following through on its translation method. Sometimes metaphors are left “untranslated.” While this may be due to the fact the point of the comparison is unclear and they feel more comfortable leaving it vague, or perhaps it could be because the translators want to leave some more explicit comparisons vague. For example, the comparison between the woman’s breasts and the fawns is left vague. Commentators disagree on what the precise nature of the comparison is. Some argue the comparison is between the softness, beauty, and grace of the dorcus gazelle which invites petting and affectionate touching. Others point out that gazelles were a delicacy served at Solomon’s table (1 Kings 4:23) and were delicious to eat. Othmar Keel, on the other hand, understands the comparison as a complex metaphor that relates to the beauty and grace of the gazelle as well as evoking iconographic images of gazelles and lotus plants, suggesting renewal and vitality — and especially emphasizing her breasts as “dispensers of life and joy” (The Song of Songs [CC; Fortress, 1994] 150-151).

Finally, translators also have to deal with euphemistic language in the Song. Most translations — whether formal or more dynamic — tend to leave the euphemistic language of the Song intact. For example, the references to her “garden” and “channels” in 4:12 and 13 are taken by many as referring to her vulva and vagina, as is her “navel” in 7:2. You don’t find that in many translations!

The question I have is whether it is better to offer a more interpretive dynamic translation when the meaning may be clear, or is it better to produce a more formal rendering and leave the questionable passage more vague? It would seem that more dynamic translations are not quite as consistent with their translation method as formal translations — and that is a good thing.

At any rate, have a great Valentine’s Day! Read through the Song of Songs with someone you love today — unless of course you are under 30 years of age!

(As an aside, I have often been puzzled by more conservative scholars who argue for Solomonic authorship of the Song and maintain that it is a celebration of human erotic love within the context of a monogamous marriage relationship. Was not Solomon known for his many wives and concubines (1Kings 11)? I don’t see how he could be held up as a modern paragon of monogamous love and faithfulness)

[Republished from 2006]

Happy Canada Day to all of my fellow Canadians.

Happy Canada Day to all of my fellow Canadians.