Ever wonder about the historical accuracy of the Nativity Story? There are a couple recent news articles on this very topic.

Most recently, Yahoo!News issued a press release on the topic (“Professor Shows Accuracy of Bible’s Christmas Story, Debunks Popular Myths“) in which Dr. Jack Kinneer, New Testament professor at the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (RPTS) in Pittsburgh, responds to some of the questions about the authenticity of the birth narratives of Jesus.

Here is an excerpt:

Myth: We can only vaguely date when Jesus was born.

Reply: “Scripture, ancient history, and modern astronomy enable us to pinpoint Jesus’ birth within the winter months of 5-4 B.C.”

Myth: Matthew made up the appearance of a star.

Reply: “Modern astronomy calculations confirm extraordinary celestial phenomena during this exact time period.”

Myth: It is implausible that the Magi would have traveled from Persia to see the star.

Reply: “It is implausible that they would not journey to see it, as they were not kings, but astrologers. It was their job to study and interpret luminaries in light of ancient prophecies.”

Myth: Jesus’ birth was at the star’s appearance, several years before the Magi’s arrival.

Reply: “Herod’s decree to kill Hebrew sons two years old and under after the Magi’s visit presumes the birth of Jesus may have just occurred. Matthew’s Greek grammar describes the birth of Jesus as the timely setting of the Magi’s arrival.”

Myth: Jesus was two to three years old when the Magi arrived.

Reply: “He was no more than a few months old.”

Myth: The dating of Christmas on December 25 accommodates a pagan feast.

Reply: “It is a calculated estimation from when the angel appeared to Zechariah during his datable priestly duties.”

Myth: The Hebrew “virgin” birth citation is embellished.

Reply: “The Isaiah 7:14 quote was interpreted as “virgin” by Jews centuries before New Testament times.”

Myth: Joseph and Mary’s flight to Egypt was a long overland journey and stay of a number of years.

Reply: It was probably a brief boat trip and a stay of only a few weeks to a month, which fits the setting of historical political events.”

I don’t have time to comment on any of this right now (I really should be marking!), though I will say that some of his points are over-stated and simplistic (read on…).

Another recent story in the Times Online (“The Real Christmas Story“), Oxford professor Geza Vermes provides a different perspective and highlights four features of the traditional nativity story that do not derive from the gospels.

…The date of Christmas on December 25 does not appear until AD334 when in a Roman church calendar the Nativity of the Lord replaces the pagan feast of the Unvanquished Sun. Before the 4th century, the birth of Jesus was celebrated on January 6 (Epiphany), or April 21 or May 20.

The idea that Joseph was an old widower with a grown-up family comes from the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James, written in the 2nd century in an attempt to make less puzzling the by then current doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary and the gospel references to brothers and sisters of Jesus. The presence of an ox and an ass in the stable is also alien to the New Testament.

As for the kings or wise men, they were neither. Matthew calls them magi, magicians or stargazers, without mentioning their number. The figure of three is no doubt deduced from the reference to the gifts left by them: gold, frankincense and myrrh.

Luke’s Gospel supplies most of the New Testament ingredients of the Christmas tale after a preliminary report on the angel Gabriel’s annunciation of two miraculous conceptions: that of John the Baptist by the post-menopausal Elizabeth and that of Jesus by Mary, a young virgin from Nazareth engaged to Joseph. Luke’s chief topics are the census decreed by Augustus and implemented by the governor of Syria, Quirinius. Both the census and Quirinius’s role in it are historically questionable as, apart from Luke, we have no evidence of a census in the kingdom of Herod or that Quirinius was in charge of Syria while Herod reigned. There was a Roman census of Judaea conducted by Quirinius, but this occurred ten years after the death of Herod in AD6.

Further peculiarities of Luke, taken over by tradition, are the birth of Jesus in an animal shed on the outskirts of Bethlehem, the angelic choir and jolly shepherds, and Jesus’s presentation in the Temple of Jerusalem on the 40th day after his birth. Matthew’s story starts with Jesus’ family tree, meant to demonstrate his messianic descent from King David through Joseph. Matthew becomes self-conscious, however, when his list reaches Jesus and seeks to avoid a phrase that would imply that Jesus was Joseph’s son. So instead of the standard formula, A begot B, B begot C, he writes: “Jacob begot Joseph, the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born.�

However, some old Greek, Syriac and Latin manuscripts tell a different tale: “Joseph, to whom the Virgin Mary was betrothed, begot Jesus.� Church tradition asserts, furthermore, that the ancient Jewish-Christian sect of the Ebionites maintained the biological paternity of Joseph.

This is the first Matthean surprise, but he heightens the drama of Joseph’s discovery that his fiancée is with child, a child that is not his. A decent man, he decides to repudiate Mary quietly without subjecting her to the rigour of Jewish law, in which sexual misbehaviour by an engaged girl is adultery punishable by death. But amid this trauma, he has a dream and learns from an angel that Mary’s condition is due to the Holy Spirit. Indeed, in her is fulfilled Isaiah’s prophecy: “A virgin shall conceive and bear a son.�

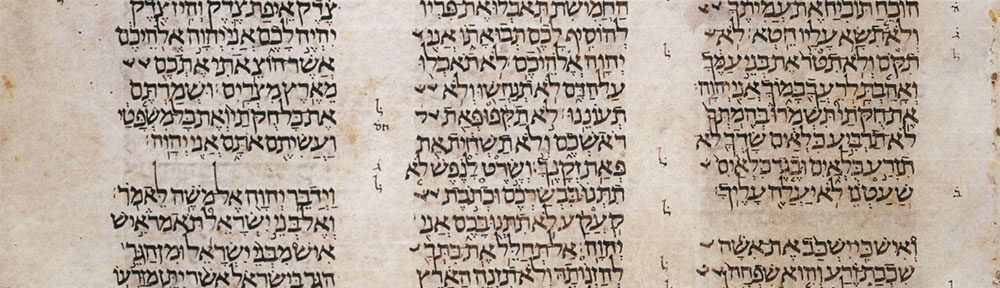

But this prophecy can be interpreted as a virgin birth only if it is read in the Greek Bible, where the word parthenos is used. For the original audience of the gospel message, who perused the Hebrew text of Isaiah, the person who conceived and bore a son was not a virgin, but an almah, a young woman. Reassured by another dream, Joseph proceeds with the marriage, but abstains from “knowing� his wife until the birth of Jesus.

In Matthew there is no census, no journey from Nazareth, nor a stable in Bethlehem. In his Gospel the oriental visitors, followers of the miraculous star of the Messiah, find Jesus in Joseph’s home in Bethlehem. The Magi are directed there after the Jewish priestly interpreters of Scripture have deduced that the Messiah would be born in that city.

Envisaged from a literary angle, the two dramatic elements characteristic of Matthew, Joseph’s psychological torture, and the panic inflicted on him by Herod’s murder plot — a story strongly reminiscent of Pharaoh’s attempt in the Book of Exodus to destroy the infant Moses and all the newborn Israelite boys — are both absent from Luke’s happy and charming tale.

Thanks to the skilled editorial hand of the Church the originally dramatic Nativity story has developed into our merry feast of Christmas.

Vermes has recently published a book on this subject: The Nativity: History and Legend (Penguin, 2006; Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com).

While I can’t really say more than that right now, I can refer you to one of the best scholarly works on the subject: Raymond Brown, The Birth of the Messiah (Doubleday, 1999; Buy from Amazon.ca | Buy from Amazon.com).