How do we read and understand individual proverbs found in the book of Proverbs? Do we take them as universal truths? Do we read them as promises from God to be claimed? Either way of reading proverbs, I maintain, is entirely wrong-headed since it falls prey to genre-misidentification. Rather than seeing proverbs as universal truths or promises from God, proper genre identification understands them as “sanctified” generalizations based on experience that may be used to guide our lives.

Proverbs are Not Promises

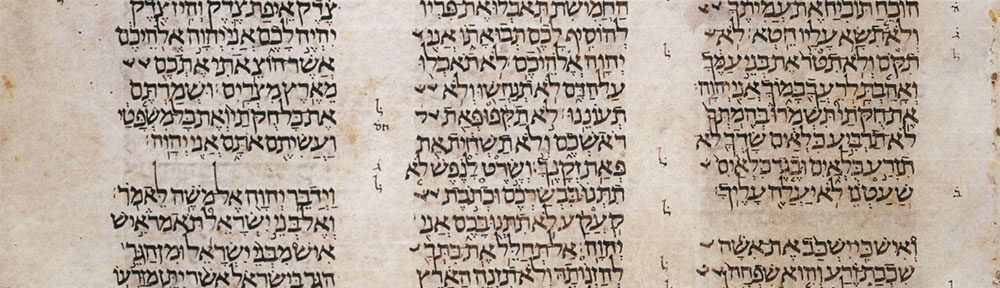

A popular approach to understanding proverbs — especially in a church context — is to see them as promises from God to be claimed by the individual believer. Take for instance, the following passage from Proverbs 3:1- 10:

1My child, do not forget my teaching, but let your heart keep my commandments;

2for length of days and years of life and abundant welfare they will give you.

3Do not let loyalty and faithfulness forsake you; bind them around your neck, write them on the tablet of your heart.

4So you will find favor and good repute in the sight of God and of people.

5Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and do not rely on your own insight.

6In all your ways acknowledge him, and he will make straight your paths.

7Do not be wise in your own eyes; fear the Lord, and turn away from evil.

8It will be a healing for your flesh and a refreshment for your body.

9Honor the Lord with your substance and with the first fruits of all your produce;

10then your barns will be filled with plenty, and your vats will be bursting with wine.

I have heard these verses preached as promises, especially vv. 5-6 and 9-10. But do these verses guarantee the results promised? If you keep God’s commandments will you enjoy long life? If you trust in Yahweh will you enjoy straight paths? (I won’t even touch on the common misapplication of relating this proverb to divine guidance). If you fear Yahweh will you be physically healthy? Despite what late-night prosperity preachers claim, if you tithe your first fruits, will God reward you materially? Are these promises to be claimed?

Or how about this proverb:

Train children in the right way, and when old, they will not stray (Prov 22:6)

As a Christian parent I would like to “claim” this, but that is not the way proverbs work. This is a generalization based on experience. Perhaps in the appropriate circumstances this and other proverbs are true, but I think we all know enough real life situations where this has not been the case. If proverbs are promises, then either God is unfaithful or we don’t claim them with enough faith.

What is more, this sort of “claim it” approach to proverbs is also contradicted by other wisdom traditions found in the Bible. The book of Job poignantly illustrates that “trusting in Yahweh” doesn’t guarantee health and wealth. What is more, the book of Ecclesiastes highlights that the opposite occurs far too often:

There is a vanity that takes place on earth, that there are righteous people who are treated according to the conduct of the wicked, and there are wicked people who are treated according to the conduct of the righteous. I said that this also is absurd (Eccl 8:14).

The Contextual Nature of Proverbial Truth

In order to properly understand proverbs we must distinguish between promises in admonitions and proverbial truth. Proverbs are true in the right context — they are not universally true. Take, for example, this famous pair of biblical proverbs:

“Do not answer fools according to their folly, or you will be a fool yourself” (Prov 26:4).

“Answer fools according to their folly, or they will be wise in their own eyes” (Prov 26:5).

Obviously both proverbs cannot be universally true! Nonetheless, anyone who has ever interacted with a fool knows the “truth” of both sayings. Sometimes it is appropriate to ignore fools, while at other times it is necessary to “put them in their place” with a gracious response. The wise person will know what response is appropriate in different situations: “To make an apt answer is a joy to anyone, and a word in season, how good it is!” (Prov 15:23)

The recognition that proverbs are generalizations that apply in certain circumstances really shouldn’t surprise us. This is the same way proverbs work in our culture. We have English proverbs that appear contradictory and yet are appropriate in the right circumstances. How about: “Too many cooks spoil the broth” compared to “many hands make lite work.” We can imagine circumstances where both are appropriate.

So when it comes to reading proverbs we need to keep in mind both their genre and our context. They are not promises to be claimed or universal truths; rather they are generalizations that are true in the right circumstances.

A good little introduction that I would recommend for anyone interested in how to understand and interpret the book of Proverbs is Tremper Longman’s How to Read Proverbs (InterVarsity Press, 2002; Buy from Amazon.ca or Amazon.com).