[Originally posted 14th December 2005; Note that some of the original links are now unfortunately dead due to some blogs being defunct]

Why is it interesting debates spring up right when I am swamped with end of term grading and other publishing deadlines? Well, in an effort to avoid some marking, I figured I would offer some observations on the recent debate about historiography among some bloggers (dare I say, “bibliobloggers”?!).

The Debate Thus Far

First, some background. The recent debate was sparked in part by a post by Ken Ristau reflecting his frustration with the apparent inconsistency that some scholars bring to questions of ancient Israelite historiography, especially in regards to their disregard and/or scepticism of parts of the Hebrew Bible as a historiographic source (History in the Bible?). It is important to note that Ken wasn’t claiming that the Deuteronomistic History, for example, is equivalent to modern critical historiography. All he was arguing for is a recognition that the biblical texts — with all of their ideological limitations — can be used productively and critically in reconstructing the history of Israel. It should also be noted that, if I read Ken correctly (e.g., the reference to floating axe heads), his post is directed more, though not exclusively, against some comments made by Jim West at Biblical Theology), than the published views of scholars like Davies, Lemche, Thompson, and Whitelam.

Ken’s initial post was responded to by Jim West here. In addition, Keith Whitelam (on Jim West’s Biblical Theology blog here) understood some of Ken’s criticisms directed at his scholarship and chastised Ken for not interacting with specific views, among other things. James Crossley also made some balanced observations at Earliest Christian History blog. Ken clarified his views in his response to Keith Whitelam’s concerns here, then more fully here.

A parallel series of posts examining specific archaeological discoveries that may correlate with the portrayal of Israel in the Bible has been going on among some blogs. This series was initiated by Joe Cathey’s posts on the Merneptah Stele (initial post here) and Tel Dan Inscription (initial post here) in response to Jim West’s request for “proof” for the existence of Israel. These posts resulted in a flurry of blogging activity that I don’t have the energy to track in detail, but here are some high points.

In regards to the Merneptah stele, Jim responded to Joe’s initial post here (also see here), Kevin Edgecomb responded to Jim in kind here (see Jim’s response here), while Chris Heard produced a superb post here.

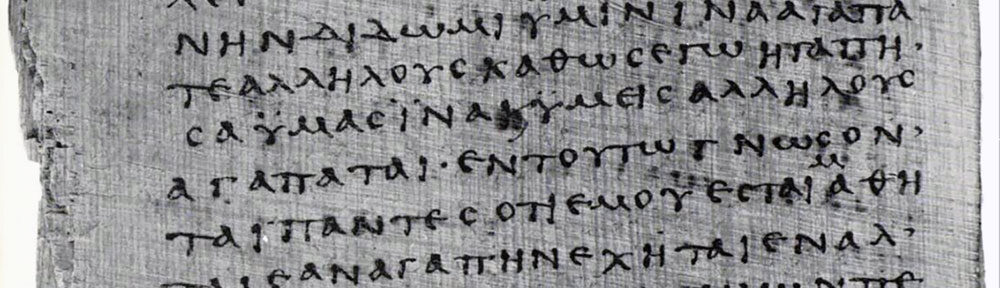

In regard to the Tel Dan inscription, Jim responded to Joe’s post here and Joe replied here, here, and once again here! And somewhere in the middle of the fray Jim replied here and here (also see Chris Heard’s reply to Jim here). Kevin Edgecomb has a number of excellent posts on the construction BÄ«t + PN in Assyrian/Aramean accounts (see here, here, and most recently here). I need oxygen… OK, I think this will be the last time I try to track a debate in the blogosphere!

I apologize if I have missed any contributions to this lively debate! In addition, you should make sure to read any comments associated with the blog posts in order to get the full picture!

Beyond “Minimalists” and “Maximalists”?

In my opinion, framing the whole discussion — and here I am not necessarily thinking only of the recent blog interchange — as a dichotomy between “minimalists” and “maximalists” is not helpful. There are not two camps, schools, or positions. If anything, the two terms represent a spectrum of possible views, with “minimalists” being at one end and “maximalists” at the other — and everyone else somewhere in the middle (I personally am a centrist — I, and only I, have a perfectly balanced perspective!). But even this portrayal of the debate is not sufficient as there are significant methodological differences between people all throughout the spectrum. For instance, “minimalist” has been used to describe scholars such as Davies, Lemche, Van Seters, Whitelam, among others. While these scholars have a number of presuppositional and methodological similarities surrounding the value of the biblical texts for modern historical reconstruction, they also have some very significant differences — especially in regards to method. This problem is exacerbated for the “maximalist” label since it seems that anyone who isn’t a “minimalist” is grouped together as a maximalist! And if you thought there were differences among the so-called minimalists, there are huge differences among so-called maximalists. In his recent article in SJOT, Lemche even starts using terms such as “maximalist critical scholars” to distinguish them from conservative/conservative evangelical/evangelical maximalist scholars. (I wonder how many “evangelical minimalist” scholars there are?)

The same observation applies equally to using labels such as “Copenhagen school,” “Sheffield school” (the use of the term “school” is more problematic as it presumes more agreement than actually exists), and “biblical revisionists.” On the other side of the debate, the label “evangelical” is used by some in an uncritical and almost derogatory way — at times equated with fundamentalist — to group scholars who have a high view of scripture, even though there is a wide spectrum of scholars who would consider themselves “evangelicals.”

I am not saying anything revolutionary here; most if not all scholars in the debate do not like the labels and have said as much in various publications — even though they continue to use them! So I think it is time for everyone to put the labels to rest and focus instead on interacting with the views of individual scholars (an especailly important step considering that many times our ad homnium or off-the-cuff comments are against views that no scholars actually hold!)

Avoiding Inflammatory Language

Even more than avoiding labels that are not heuristically useful, we need to avoid the caustic and inflammatory language that often accompanies this debate. I think we would all agree that it doesn’t help further the debate to use such language. This inflammatory language occurs in print discussions, email discussion groups, and blogs. I really wish we could all learn to play better among ourselves!

I know that some of the bantering is done tongue-in-cheek (especially in the blogosphere), though the tone of the debate does not contribute to furthering our understanding of how (or if) it is possible to write a history of Israel. We all have to do better (I include myself in the indictment). And I’m not just talking about labels that are thrown around, but statements that imply (or outright state) that so-and-so obviously hasn’t read this or that, tantamount to saying “If you weren’t such a moron, you would obviously see it my way!” That doesn’t mean we have to all agree with one another (though I believe greater miracles have happened!), but when we disagree we should do so with respect since there are learned scholars on all sides of the debate. Furthermore, when we are at the receiving end of a cheap shot or ad homnium argument, we should try our best to not respond in kind, but instead respond with appropriate restraint.

Focusing on Real Issues and Real Differences

Anyone familiar with the debate surrounding the history of Israel knows that there are a number of real issues dividing scholars. An important question that needs to be asked is at what level are the real differences? Most of the time the real differences are not on the surface, but are at lower levels. These lower levels may be methodological, or may be presuppositional and metaphysical. In any debate, it is essential to be able to identify at what level the disagreement exists. In a recent IBR article, V. Philips Long quotes E. L. Greenstein’s comments which I believe are quite appropriate:

in biblical studies we often argue as though we all shared the same beliefs and principles, as though the field were all built upon a single theoretical foundation. But it is not…. I can get somewhere when I challenge the deductions you make from your fundamental assumptions. But I can get nowhere if I think I am challenging your deductions when in fact I am differing from your assumptions, your presuppositions, your premises, your beliefs.

For example, let’s examine the recent blog debate about the Tel Dan stele. All parties — even Jim — appear willing to concede that the phrase in question is “house of David” (this is not the case in the larger debate where alternative readings are proposed; in which case there would be differences on the level of exegetical judgements). But then at the next step taken by Joe Cathey and Chris Heard, correlating the David of the inscription with the David mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, Jim West demurs. I believe this highlights some low-level differences among those engaged in the debate. Reading between the lines, I would suggest that Jim West has both methodological and metaphysical objections to reading the Hebrew Bible as a historical source, Chris Heard is arguing on the level of the historical critical method and bracketing any personal metaphysical commitments (Ken Ristau appears to be operating at this level as well), while Joe Cathey is probably similar to Jim West, though his methodological and metaphysical commitments likely differ considerably from Jim’s. The end result is that the discussion stalls and a stalemate is declared.

Meaningful and Productive Debate

The $60,000 question is how can we avoid such disagreements? Or stated positively, how can we engage meaningfully in a debate with whom we may have significant methodological and metaphysical differences? The first step would be to be up front about our lower-level commitments. We need to be clear about our method and our metaphysics. This sort of full disclosure will not, of course, produce peace and harmony among us (we know from pop culture that only Coca-Cola can do that!); but it will help us understand where we all are coming from. After this, we can then see if we can find a “middle discourse” to engage one another. We need to agree on the rules of the game before the game starts. Here I wonder if the most fruitful approach may be to work on the level of the historical-critical method and bracket any metaphysical commitments — at least initially. Then, for those of us who may share similar metaphysical commitments, we may take the conversation further.

Of course, perhaps I am being hopelessly naive to think that we can ever really “bracket” our metaphysical commitments, or that we can ever agree on method (there really isn’t any such thing as the historical-critical method!), or that we could even agree on what argument is more plausible than another.

What we can agree on, however, is to treat each other with respect, try to understand each other’s views, and stop with the labels, ad homnium arguments, and making grandiose claims of “proof” on insufficient evidence.

Well, I’ve babbled on enough. Back to marking!