The End of Historiography?

We had an interesting discussion in my course on ancient historiography the other day. We were discussing Arnaldo Momigliano’s article, “Persian Historiography, Greek Historiography, and Jewish Historiography,” in The Classical Foundations of Modern Historiography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), and how historiographic writing in Judaism died off in the late Second Temple period (i.e., after the writing of 1 Maccabbees). According to Momigliano, the reason for the demise of the specifically Hebrew way of writing historiography is due in part to the disappearance of the Jewish state, although the primary reason why Jews lost interest in historical research was the singular focus on the Torah that developed in this period. Interestingly, a small Jewish sect that emerged in the first century CE retained an interest in historiography. This sect is, of course, the early Christ followers who preserved a historiographic record in the biographies of Jesus (better known as the gospels) and, more specifically, in the Acts of the Apostles.

The End of Prophecy?

I don’t think many would contest Momigliano’s perspective on the “end” of Jewish historiography at the turn of the common era, though I could be wrong. One of the students in my class brought up a related question about the end of prophecy during that same period. The traditional (or do I dare say “canonical”) position is that prophecy ceased with the closure of the Hebrew canon. This perspective appears to be reflected in 1 Maccabees 4:46 where in the process of cleansing and rededicating the temple, Judas Maccabeus stores the defiled stones of the altar of burnt offering, “until a prophet should come to tell what to do with them”; and more explicitly in 1 Macc 14:41 where it says, “The Jews and their priests have resolved that Simon should be their leader and high priest forever, until a trustworthy prophet should arise….” Both of these texts seem to assume that there was no prophet at the present time and they had to make do until one arises — the hope of which was likely inspired by Deuteronomy 18:15. This perspective is also held by Jewish authors such as Josephus, who after narrating the biblical history of Israel, notes that, “From Artaxerxes to our own time the complete history has been written, but has not been deemed worthy of equal credit with the earlier records, because of the failure of the exact succession of the prophets” (Against Apion 1.41). This view is also reflected in the much later teaching of the Talmud, where it reads: “When the latter prophets died, that is Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, then the Holy Spirit came to an end in Israel. But even so, they made them hear [messages] through an echo” (t.Sot 13.3).

What is noteworthy, however, is that while the “official” view may have been that prophecy ceased after the closure of the canon, its seems that no one informed the common person! Even Josephus is inconsistent. He appears to hold the official party line, yet he notes that John Hyrcanus I (135-104), “was accounted by God worthy of three of the greatest privileges, the rule of the nation, the office of high priest, and the gift of prophecy; for the Deity was with him and enabled him to foresee and foretell the future” (War 1.68-69). Some suggest that Josephus considered himself a “clerical” prophet, though he never uses the actual term “prophet.” Josephus also mentions a number of individuals among the Essenes who “profess to tell the future”, as well as some from among the Pharisees. He further (negatively) identifies a number of “popular prophets”, such as Theudas, Joshua ben Hananiah, who managed to gain significant followings among the masses. John the Baptist, according to the Gospels, appears to fit nicely in to this category of popular prophet.

The End of the Matter…

So, did prophecy cease after the “canonical” prophets? Yes and no. While Josephus seems to suggests that the type of prophet and prophecy found in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament ceased, there were many individuals who — wrongly or rightly — were willing to don the prophetic mantle and proclaim God’s message to the people.

I have always imagined that during the time of Christ there would have been many self-proclaimed prophets around, kind of like this great scene from Monty Python’s The Life of Brian:

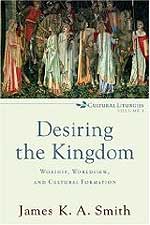

In the second sermon I painted a profile of what I believe are some important characteristics of an “intellectually mature believer.” First and foremost, I underscored the importance of “epistemic humility” based on our fallenness, fallibility and finitude. The second characteristic was openness. More particularly, I emphasized the importance of openness to God and Scripture, openness to all truth (no matter where it may be found), and a genuine openness to others. By openness I do not mean a wishy-washy relativism, but something called “critical commitment” where you know what you believe and why and hold it with faith, moral courage, and epistemic humility. My final characteristic of an intellectually mature believer was that he or she should have as a goal integration. Here I was arguing for a somewhat unified/integrated Christian perspective on the world and our faith (I consider the modifier “somewhat” very important). This “unified view” is often referred to as a “worldview” or “world and life view.” While there are a number of limitations to the concept of a worldview (especially the notion that there is such an animal as “the Christian worldview” or that worldviews are somehow impervious to culture rather than embedded in culture), I still find it a helpful concept for thinking about thinking.

In the second sermon I painted a profile of what I believe are some important characteristics of an “intellectually mature believer.” First and foremost, I underscored the importance of “epistemic humility” based on our fallenness, fallibility and finitude. The second characteristic was openness. More particularly, I emphasized the importance of openness to God and Scripture, openness to all truth (no matter where it may be found), and a genuine openness to others. By openness I do not mean a wishy-washy relativism, but something called “critical commitment” where you know what you believe and why and hold it with faith, moral courage, and epistemic humility. My final characteristic of an intellectually mature believer was that he or she should have as a goal integration. Here I was arguing for a somewhat unified/integrated Christian perspective on the world and our faith (I consider the modifier “somewhat” very important). This “unified view” is often referred to as a “worldview” or “world and life view.” While there are a number of limitations to the concept of a worldview (especially the notion that there is such an animal as “the Christian worldview” or that worldviews are somehow impervious to culture rather than embedded in culture), I still find it a helpful concept for thinking about thinking. I just returned from a nice long weekend away with the family. This was one of our annual trips that with a couple other families. We took the kids tubing at the lake, went ATV-ing, sat around the campfire and played various games. All in all it was a great weekend. Another regular part of this weekend is that the guys head out early one morning for a round of golf. I enjoy golf, although I am not very good at it and I only seem to get out half a dozen times a year. I had one of the best games in years earlier this summer when I shot a 47 (on 9 holes) on a father’s day outing.

I just returned from a nice long weekend away with the family. This was one of our annual trips that with a couple other families. We took the kids tubing at the lake, went ATV-ing, sat around the campfire and played various games. All in all it was a great weekend. Another regular part of this weekend is that the guys head out early one morning for a round of golf. I enjoy golf, although I am not very good at it and I only seem to get out half a dozen times a year. I had one of the best games in years earlier this summer when I shot a 47 (on 9 holes) on a father’s day outing.