[Originally posted 3rd July 2005]

There are a total of 37 places where the LXX Psalter has either additions (13x) or expansions (24x) to the superscripts in comparison to the MT Psalter. While these may be classified in a number of ways, I will discuss them under four headings: personal names; genre designations, liturgical notices, and situational ascriptions. This blog entry will focus on personal names. (Note: Chapter and verse references are to the MT with the LXX indicated in parentheses).

Personal Names in the LXX Psalm Superscriptions

In the MT many of the psalms have references to personal names in the superscripts (typically with the preposition ל l). Seventy three psalms contain David; others have Asaph (12x; Pss 50; 73–83); the sons of Korah (11x; Pss 42; 44-49; 84-85; 87-88); Solomon (Pss 72; 127); Ethan (Ps 89), Heman (Ps 88), Moses (Ps 90), and possibly Jeduthun (Pss 39; 62; 77). With rare exceptions, the construction lamed + name is rendered with an articular dative. This includes all of the Asaph psalms and virtually all of the Korahite psalms (there are two contested cases where υπεÏ? + genitive is used: Ps 46(45) and 47(46)). In connection with the David psalms, Pietersma has argued that the six places that Rahlfs uses a genitive in his lemma text should be read as datives. Of the two psalms with Solomon in their titles, one is translated by a dative (Ps 127(126)), while the other is rendered by εις Σαλωμων “for Solomon” (Ps 72(71)).

David in the Septuagint Psalter

In the LXX there are a number of instances where personal names are added, including Jeremiah and Ezekiel in Ps 65(64); Haggai and Zechariah in Ps 146(145); 147:1-11(146); 147:12-20(147); and 148. Most of the changes in personal names, however, relate to David, the “sweet psalmist of Israel.” In 13 cases the LXX adds a reference to David (Pss 33(32); 43(42); 71(70); 91(90); 93(92); 94(93); 95(94); 96(95); 97(96); 98(97); 99(98); 104(103); 137(136). (I should also note that there are two instances where references to David are omitted in the Greek tradition: Pss 122(121) and 124(123)). In all but one instance (Ps 98(97)), the LXX adds this association to psalms that are untitled in the MT. The question that immediately comes to mind are whether these additions reflect a different Hebrew text or are the product of transmission history. Unfortunately, it is difficult to gain any critical purchase on this question since Ï„á¿· Δαυιδ is the default rendering of לדוד. In three cases it is more than likely that the additions reflect a different Hebrew text, as there is textual evidence to support the variant reading, whether among a few Masoretic texts (43(42)), or among the DSS (e.g., 11QPsq has לדוד in Ps 33(32); and 11QPsa and 4QPse also have לדויד in Ps 104(103).

The remaining ten instances are more difficult to access. Al Pietersma, in his study “David in the Greek Psalms” (VT 30 (1980) 213-226), suggests that the Davidic references in Pss 71(70); 91(90); 93(92); 95(94); 96(95); and 97(96); may be called into question because other elements of the LXX superscripts are clearly secondary. While this is essentially a “guilty by association” argument, it’s the best we can do considering the evidence. This leaves four superscripts that add an association with David: Pss 94(93); 98(97); 99(98); and 137(136). It is almost impossible to make any determination with Ps 94(93), as the superscript is uncontested. As a royal psalm, it may be understandable why Ps 98(97) would attract a Davidic superscript, though this does not help explain Ps 99(98) (contra Pietersma). The only superscript where some judgment may be made is Ps 137(136). There is quite a bit of variation among the textual witnesses, with many of them including an ascription to Jeremiah, and some conflating the two and associating the psalm with David and Jeremiah. The textual rivalry between David and Jeremiah could be an indication that the psalm was originally untitled, as it is in the MT tradition and Qumran.

Jeremiah & Ezekiel in the Septuagint Psalter

As noted above, some Greek texts of Ps 137(136) include a reference to Jeremiah in their superscripts. The association with Jeremiah in the Greek tradition is perhaps understandable considering the psalm’s exilic setting, though according to biblical tradition Jeremiah never goes to Babylon. There is a tradition, however, that places Jeremiah in Babylon. In fact, 4Baruch 7:33-36 Ps 137(136):3-4 is actually put into the mouth of Jeremiah. The text reads as follows:

For I [Jeremiah] say to you that the whole time we have been here, they have oppressed us, saying “Sing us a song from the songs of Zion, the song of your God.” And we say to them, “How can we sing to you, being in a foreign land?”

While there is a possibility that the superscript led to 4Baruch making the association, it seems more plausible the other way around because 4Baruch has Jeremiah in Babylon, where singing the psalm makes sense. In addition, in 4Baruch there is no indication that Jeremiah is quoting Scripture.

The reference to Jeremiah in Ps 137(136) is not the only one found in the LXX Psalter. The prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel are mentioned together in Ps 65(64). The full superscript reads as follows:

εἰς τὸ τέλος ψαλμὸς Ï„á¿· Δαυιδ ᾠδή ΙεÏ?εμιου καὶ Ιεζεκιηλ á¼?κ τοῦ λόγου τῆς παÏ?οικίας ὅτε ἔμελλον á¼?κποÏ?εύεσθαι

To the end. A psalm for David. A song. Of Jeremiah and Ezekiel from the account of the sojourning community, when they were about to go out.

The superscript is somewhat contested, though Rahlfs considered it OG. What is interesting about this superscript, is that like the previous example, there is a double association: a connection with David and with Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Unlike the previous example, it is not clear what triggered the association with Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Within the psalm itself there are no explicit connections with these prophets or the return from exile in general. The reference to “Zion” and the addition of “Jerusalem” in v. 2 may suggest this is one of the “songs of Zion” mentioned in Ps 137. While these (and others I won’t bore you with) readings of the Greek translation may provide some clues as to why the association was made, it is more certain that the association is due to an inner-Greek development rather than a different Hebrew parent text. This is almost certain due to the fact that the superscript employs the atypical conjunction ὅτε, and that the grammatical construction of the modal μελλω (“about to”) plus a complementary infinitive is never found elsewhere in the LXX Psalter, and thus is not congruent with the translator’s technique.

Haggai & Zechariah in the Septuagint Psalter

The final two individuals that we meet unexpectedly in the superscript of the LXX Psalter are the post-exilic prophets Haggai and Zechariah. Ps 146(145); 147:1-11(146); 147:12-20(147); and 148 all include Αλληλουια, Αγγαιου καὶ ΖαχαÏ?ιου “Hallelujah. Of Haggai and Zechariah” (or “A Hallelujah of…”). If you look beyond Rahlfs’ text, then Haggai and Zechariah also show up in Ps 149 and 150, as well as 111(110), 112(111), and even 138(137) and 139(138). Of courses, not all attestations are as strong textually, though it is interesting to note how the tradition surrounding Haggai and Zechariah grew.

How the association of Haggai and Zechariah with these psalms arose is a perplexing question. F. W. Mozley (The Psalter of the Church, Cambridge University Press, 1905, p. 188), conjectures that Haggai and Zechariah were compilers of a small collection of psalms from which these psalms were taken. While that may be the case, a more plausible solution may be to look in these psalms for connections to the post-exilic community. Both Martin Rösel (“Die Psalmüberschriften Des Septuaginta-Psalters,” in Der Septuaginta-Psalter, Herder, 2001, pp. 125-148) and Al Pietersma (“Exegesis and Liturgy in the Superscriptions of the Greek Psalter,” in X Congress of the IOSCS, Oslo 1998, Society of Biblical Literature, 2001, pp. 99-138) appeal to Psalm 147(146) as the text that triggered the initial association. Verse 2 in the LXX has an explicit reference to the return from exile. The texts read as follows:

οἰκοδομῶν ΙεÏ?ουσαλημ á½? κÏ?Ï?ιος καὶ Ï„á½°Ï‚ διασποÏ?á½°Ï‚ τοῦ ΙσÏ?αηλ á¼?πισυνάξει

The Lord is the one who (re)builds Jerusalem; and he will gather the dispersed [diaspora] of Israel

The translation of the Nif’al participle from × ×“×— “drive away” by διασποÏ?α is atypical. Elsewhere the translator renders × ×“×— by εξωθεω“to expelâ€? (5:11) or απωθεομαι “expel, banish” (62[61]:5). Rather than these more general terms, in the passage under question he employs a technical term for the exilic dispersion, διασποÏ?α. Perhaps significant, is the fact that this term also shows up in some witnesses in connection with Zechariah in the superscript to Ps 139(138). This reference to the exilic dispersion in Ps 147 may have spawned the initial association with two prominent figures of the return, Haggai and Zechariah, which then expanded to include other psalms. The fact that the names are in the genitive may suggest these superscripts are products of transmission history, as it is unclear what the Hebrew text could have read to produce such a translation (If the Hebrew was lamed + name, then you would expect an article in the Greek, and there is no precedent for a construction “the hallelujah of Haggai and Zechariah”).

Personal Names and Authorship

One question that comes up in examining the LXX superscripts is how the translator understood the notion of authorship. Interestingly, it appears to be the case that the Greek translator (one of the earliest biblical interpreters) did not see the personal names in the superscripts as an indication of authorship, as a genitive construction would be expected. For example, Didymus the Blind (a 4th century Alexandrian theologian) makes the distinction in the Tura Psalms commentary in connection with Psalm 24:

(Ψαλμος τω δαυιδ): εις τον δαυιδ ο ψαλμος λεγεται αλλο γαÏ? εστιν “του δαυιδ” ειναι και αλλο “τω δαυιδ” λεγεται, οταν η αυτος αυτον πεποιηκως η ψαλλων. “αυτω” δε λεγεται, οταν εις αυτον φεÏ?ηται.

The psalm says “to David,” for others are “of David” and others “to David.” It says “of David,” when he made/wrote it or sang [it]. But it says “to him” when it was brought to him.

So while the Old Greek translation does not seem to indicate authorship, the growing trend in later witnesses is to spell out authorship explicitly by using the genitive. This suggests that the emphasis on individual authorship grew with time.

The evidence from the Greek Psalter fits nicely with a theory of Burton Mack’s I came across a number of years ago in an article entitled, “Under the Shadow of Moses: Authorship and Authority in Hellenistic Judaism” (SBL Seminar Papers 21 (1982) 299-318). In this article Mack argues that the interest in individual authorship only developed as Israel interacted with Hellenism. In the same way that the Greeks had their famous individuals, so too Judaism began to emphasize their own: Moses and the Pentateuch, Solomon and wisdom literature, and — as is clear from the Greek Psalms — David and the Psalter. The growing Davidic connection in the LXX Psalter is also paralleled in 11QPsa, where the prose piece notes that David composed over 4000 psalms “by the spirit of prophecy.”

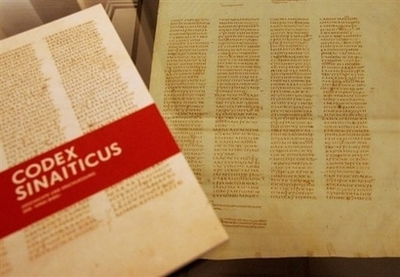

The first online phase of the Codex Sinaiticus digitization project headed by the Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing at the University of Birmingham, in cooperation with the British Library and the three other holding libraries, will be going live Thursday 24 July 2008 at www.codexsinaiticus.org.

The first online phase of the Codex Sinaiticus digitization project headed by the Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing at the University of Birmingham, in cooperation with the British Library and the three other holding libraries, will be going live Thursday 24 July 2008 at www.codexsinaiticus.org.