Translation Theory 101

All translators agree that the task of translation is to communicate the meaning of the original source language in the target/receptor language (at least I haven’t met one who wanted to obscure the original meaning!). The debate revolves around what linguistic form should be used in translation. Two of the most popular alternatives — which represent two ends of a spectrum — are “formal” and “dynamic” translations. Here is a chart that identifies were many modern translations would fit on the spectrum (it is obviously not exhaustive and represents my ad hoc evaluation).

With formal (“word for word”) translations the syntax and word class of the original language tend to take precedence over that of the target language. Thus, nouns beget nouns, verbs beget verbs, etc. In contrast, dynamic (“sense for sense”) translations restructure the form of the original into the natural syntax and lexicon of the receptor language in a way that preserves the semantic meaning rather than the form of the source. Compare these examples (my dentist especially likes the first one):

- “I gave you cleanness of teeth in all your cities, and lack of bread in all your places, yet you did not return to me,” says the LORD (Amos 4:6 NRSV, JPS, NASB, KJV).

- “Igave you empty stomachs in every city and lack of bread in every town, yet you have not returned to me,” declares the LORD (Amos 4:6 NIV, NLT).

- And he came to the sheepcotes by the way, where was a cave; and Saul went in to cover his feet: and David and his men remained in the sides of the cave (1Sam 24:3 [Heb. v 4] KJV, NJB).

- He came to the sheep pens along the way; a cave was there, and Saul went in to relieve himself. David and his men were far back in the cave. (1Sam 24:3 NIV, NRSV, NLT, NASB).

(See here for a discussion of the Hebrew idiom of “covering one’s feet”)

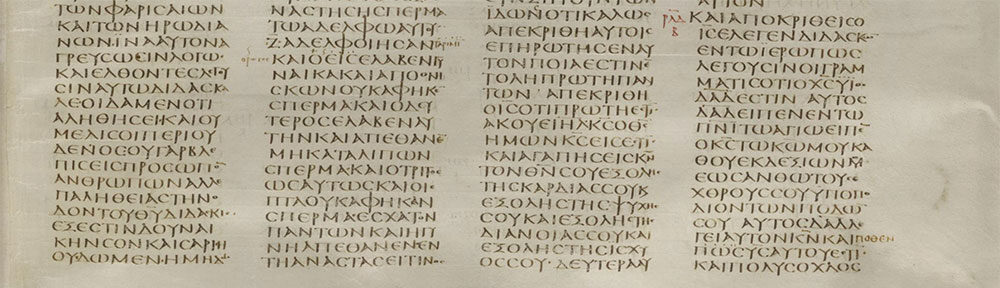

In ancient times, formal translation was dominant (e.g., the majority of the translators of the LXX), while in modern times dynamic translation tends to be favoured. The tension between the two methods is seen in any modern translation — whether of the Bible or not. I was reading a new translation of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina and the translator highlighted the same tension between formal and dynamic translation. On the one hand the primary purpose was to make Tolstoy readable (dynamic), but she also wanted preserveseve some of Tolstoy’s abrupt style (formal). When it comes right down to it, it is quite rare for a translation to be entirely consistent. Formal translations will unpack some idioms and expressions in the source language using dynamic equivalence while leaving others, and some dynamic translations will employ their theory inconsistently, especially when it comes to a traditional passage.

Denotative and Connotative Meaning

Another significant — and difficult — aspect of translating from one language to another is rendering the connotative meaning of the original. “Connotative” refers to the emotive sense of a word (denotative meaning refers to the referential sense of a word). Connotative meaning recognizes that words have a history and have definite connotations in different cultural contexts. The trick is trying to represent these accurately in translation. A well-know example where most translations fail to convey the connotative meaning of the original is Jesus’ response to his mother at the wedding in Cana:

- “Woman, what concern is that to you and to me?” (John 2:4 NRSV, NASB, KJV)

- “O woman, what have you to do with me?”(John 2:4 RSV)

- “You must not tell me what to do, woman” (John 2:4 GNB)

In all of these cases it would seem to most English readers that Jesus is giving his Mom some attitude when he addresses her as “woman” (γυνή). In contrast, γυνή appears to be a term of endearment and affection in the first century (cf. Josephus, Ant. 17.74). I would think it would be better for translations to not even translate the word like the NLT, or at the very least add a modifier to help communicate the connotations of the term. This is what the NIV did in its translation: “Dear woman, why do you involve me?”

Dogs, Urine, and Connotative Meaning

OK, now we’re at the passage that I wanted to talk about all along. One Hebrew phrase that I think pretty much all modern translations fail miserably to convey its connotative force is found in 1 Samuel 25:22 and five other times in the Hebrew Bible. Compare the following translations:

- “So and more also do God unto the enemies of David, if I leave of all that pertain to him by the morning light any that pisseth against the wall” (KJV).

- “May God do so to the enemies of David, and more also, if by morning I leave as much as one male of any who belong to him” (NASB, NIV, NRSV, NLT, BBE, NAB, NKJV, TEV, etc).

Virtually all modern English translations that I have checked render the Hebrew phrase משתין בקיר (lit. “urinate against the wall”) with “male.” Two exceptions are the ASV which has “man-child” and the NJB which renders the phrase with the rather obscure “manjack” (“manjack” appears to be an emphatic way of saying “all of them”). The phrase occurs with similar contexts of cursing and killing in 1Sam 25:34; 1Kings 14:10, 16:11, 21:21; and 2Kings 9:8.

Many scholars think the term is a vulgar way to refer to male humans who may urinate in public whenever nature calls or young children who would be even less bashful (as the ASV evidently understood it). I think a better understanding is to see it as a derogatory comparison to male dogs who are more than eager to urinate against a wall (or anything else that is close). This appears to be one of the early understandings of the phrase (see the Talmud, Midrash on Samuel, Rashi, etc.) and a fairly popular modern one. Whether or not it is referring to males or comparing them to male dogs, it is clearly a contemptuous, vulgar, and pejorative way to refer to men. Translating it simply as “males” fails to convey the negative connotations of the original Hebrew.

The question remains, why would most modern translations not render this phrase in a way that brings out its connotative sense? I would suggest that this is a case of modern translations — both formal and dynamic — wimping out. You can’t have “urinate” in the Bible, much less “piss”! It’s the same concern for a false sense of propriety that softens the translation of ש×?גל×? in the Hebrew Bible or σκÏ?βαλα in the New Testament, among others. This is just one example of where modern translations soften the biblical text. I think that tendency blurs the distance between the horizon of the text and the horizon of the reader which is a necessary precaution against mis-reading an ancient text. While this is more of a problem for dynamic translations, as can be seen from this example, it also is a problem for more formal translations.

Pingback: Codex: Biblical Studies Blogspot » Blog Archive » Alter on the Psalms

[…]All translators agree that the task of translation is to communicate the meaning of the original source language in the target/receptor language (at least I haven’t met one who wanted to obscure the original meaning!). The debate revolves around what linguistic form should be used in translation. Two of the most popular alternatives — which represent two ends of a spectrum — are “formal” and “dynamic” translations.[…]

Pingback: Codex: Biblical Studies Blogspot » Blog Archive » Bad Sermon: “Him that pisseth against the wall”

Pingback: kata Drew » Blog Archive » Him that Pisseth against the Wall